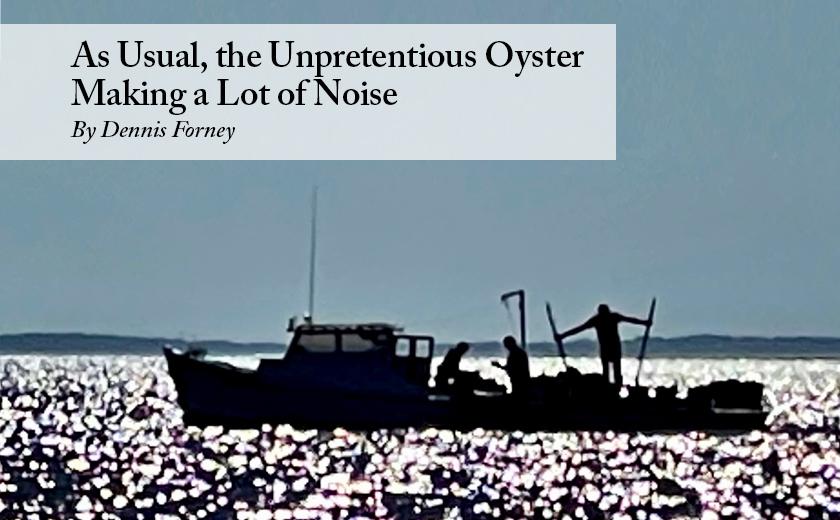

Oyster tongers and cullers work the Deep Neck Bar in Broad Creek on a mild, mid-November afternoon. Photo by Dennis Forney

“The wild oyster fishery faces a daunting future, both environmentally and culturally. The cost of wild harvesting continues to climb and the return on investment continues to decline. The next generations of watermen are pondering less demanding and more lucrative career paths, as early mornings on the water and long, physically arduous days have less appeal.” – Peter Franchot, Maryland comptroller and candidate for governor

What could be less pretentious than an oyster?

It lives its life quietly, underwater, creating its own shelly habitat on the bottom of our creeks, rivers and bays as it constantly regenerates. It asks little and provides so much to us, helping to keep our waters clear and productive, heaping our tables with delicious protein that can be enjoyed in so many ways, reminding us that staying quiet and tending to our own business is good for our blood pressure.

All it asks of us is to keep our pollution to ourselves, not in its home. And in that, of course, we also benefit tremendously.

Forget the zero sum game, it is the meek that shall inherit the earth.

AN HOUR BEFORE daylight each morning, watermen here in Grace Creek where I live fire up their diesel engines and outboards, switch on their navigation lights, and begin parading out to the oyster grounds of Broad Creek – south of St. Michaels – and the mighty Choptank beyond.

On clear, moonlit nights like we have this week, the water surface sparkles white and black before the pinks, oranges and reds of dawn color and herald the new day. Orion slowly disappears into the south while a few planets hang on before joining the hunter constellation. Then, the sun up, the reflected palette of autumn’s changing leaves along the banks of the creek upstage the colors of sunrise for a week or two.

The transition from night to day makes for a nice scene as watermen begin their work day.

I’m told that Broad Creek, and the Deep Neck Bar in particular, are among the Chesapeake’s most productive wild oyster beds. Last year about this time, one waterman said a survey showed 2,500 spat on a single bushel taken from that bar. State officials confirmed that stat. Talk about productive! The waters out there are clear and flush steadily.

All those spat – tiny oysters that grow to big oysters – are nature’s way of celebrating harmony and balance in the ecosystem.

Not a bunch of noise and confetti, but a quietly boisterous celebration nonetheless.

MISCELLANEOUS OYSTER BUZZ – Here’s what I know from listening and reading this week.

-

Heading into the holiday season, watermen are getting between $30 and $40 per bushel for their day’s toil. This time last year,with the economy gripped by the pandemic and many restaurants closed, the price was closer to $20 and there were many days when there was no market.

-

The Bay Journal reported this week that the commissioners of Somerset County successfully filed for an injunction to stop the impending creation of an oyster restoration area in the Manokin River just above Crisfield. Due to a shortage of oyster shell on which to spread seed oysters to rejuvenate that river’s oyster stocks, the state planned to deploy stone on the bottom as a substitute. Crabbers objected to the use of stone because it tends to snag trotlines much more so than shell. The Manokin project is part of the larger Chesapeake Bay restoration plan which aims to help clean the bay’s waters by rebuilding the Bay’s once flourishing oyster populations and their natural filtering ability.

-

Meanwhile, in the lower Chester River, according to a report in the Easton Star Democrat, a partnership of private conservation and county and state-level government groups joined forces to plant 14 million spat on the 4.5 acre Coopers Hill bar. The aim is to create a self-sustaining oyster population to benefit watermen and nature.

-

The Ferry Cove oyster hatchery near Sherwood in Talbot County – expected to become one of the largest hatcheries on the nation’s east coast – is completing construction. Production should begin soon. The private enterprise plans to sell a variety of oyster seed to aquaculture operations far and wide and to any other entities – public and private – looking to grow oysters for business and environmental purposes.

-

Candidate Franchot created a stir among wild oyster harvesters when he stated he felt there was greater opportunity in the future for aquaculture production of oysters as opposed to in the independent harvesting of wild stocks.

As quiet and unpretentious as the oyster is, the noise that surrounds it and the occasional beautiful pearl it produces remind us of its tremendous importance to our Delmarva culture.

Contractors are putting final touches on the Ferry Cove oyster hatchery near Sherwood and Lowe’s Wharf in Talbot County.

Jacques T. Baker, Jr. says

Another good article, Dennis – keep on truckin’!

Best,

Jacques Baker