Italian artist Giotto di Bondone of Florence (c1267-1337) is considered by art historians to be the most significant artist of his time. They credit him with bringing the art of the Middle Ages into the Renaissance. All of the great Renaissance artists of the next centuries, from Masaccio to Michelangelo, studied Giotto’s paintings intensely. Among his most significant works are his frescoes in the Arena Chapel in Padua, Italy.

The Arena Chapel, so named because its location is the site of an ancient Roman arena, is also called the Scrovegni Chapel. Enrico Scrovegni built the chapel as an offering to God to atone for his father’s sin of usury. This fact was well known. Dante placed Scrovegni in one of the circles of hell in the Divine Comedy. Giotto designed the chapel with windows on the south side, where the sun would shine in the longest, leaving the opposite wall without any disruption. He and a crew of 40 assistants began painting in1305/06 and completed the work in1309.

The Chapel (68.5’ x 26.25’ x 41.5’) is covered with the story sequence of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin, grisaille images of the Vices and Virtues, the Last Judgment, and a star-filled blue sky. Each scene was painted with decorative borders and Old and New Testament figures who relate to each scene. Even the lower wall was painted to resemble marble.

The entire chapel was painted in wet fresco. Starting from the top of the wall, wet plaster was applied to an area that could be completed in one day. A full-size cartoon (preparatory drawing) was sketched on the wet plaster and then the wall was painted. It was calculated that it took 625 days to paint the walls, one section at a time, before the plaster dried. Painting started at the top of the wall and continued around the entire wall, moving to the middle level, and finally to the lower level.

Giotto’s eleven scenes of the “Life of the Virgin” tell the story of Mary before she gave birth to Jesus. The story begins on the upper level of the wall, starting at the right of the altar, continuing around the top, and ending at the left side of the altar. The “Angel of the Annunciation” can be seen at the left across from “Virgin Mary” at the right. The fresco cycle continues around the Chapel wall, stories of the birth of Christ on the middle level, and the death of Christ on the lower level. The entry wall (not pictured), opposite the altar, contains the “Last Judgment.”

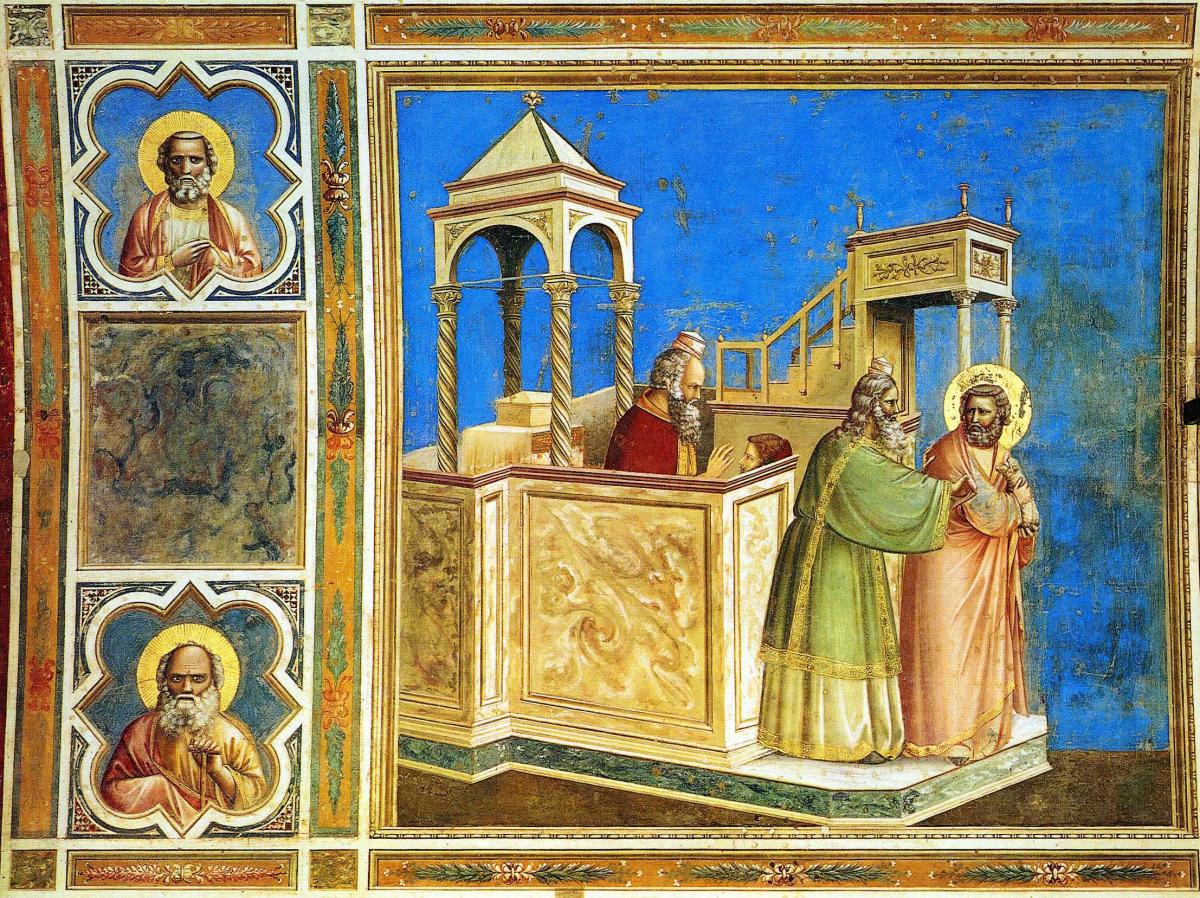

In the early 14th Century, scenes from the life of Christ and the life of the Virgin were among the most desired subjects. The story of Mary’s parents Joachim and Anna was told in the apocryphal Gospels of James (Protoevangelium) and Pseudo-Matthew (The Infancy Gospels), and in the Golden Legend of Varagine. They were pious Jews who lived in Jerusalem and gave dutifully to the Temple. They were an aging and childless couple, and childlessness was thought to be the will of God and a sign of His displeasure. “Joachim Expelled from the Temple” depicts this part of the story.

One of Giotto’s significant contributions to art can be witnessed in the brilliant ultramarine blue sky that provides the background for all the scenes. What would seem obvious, painting the sky blue, had not been the practice before Giotto. Traditionally the sky was painted gold to represent heaven. For the first time, viewers witnessed religious scenes taking place on earth. Ultramarine was the most expensive color available to artists because it was made from hard-to-find lapis lazuli, and the method of production was difficult. Enrico Scrovegni, the wealthy patron, was able to provide the funding.

Giotto also was the first artist to give his figures a sense of mass and weight. They were no longer one-dimensional figures that appeared to float above the earth; they were placed solidly on the ground. Giotto applied light and shadow to the garments and faces, thus creating a more three-dimensional effect.

Giotto’s ability to create facial expressions was still very limited, but exceeded the skills of his contemporaries. Although his figures have weight, they are covered with heavy clothing, because accurate body proportions, anatomy, and age escaped him. Similarly, he lacked the ability to create a three-dimensional space and substantial architecture. The wall, thin spiral columns holding the canopy, stairs leading up to the pulpit, and angles of the structures are inaccurate and flimsy. Three-dimensional perspective would not be possible for another 100 years. However, Giotto’s rendering of the marble, the spiral columns and Corinthian capitals are stylistically accurate for church architecture of Giotto’s time.

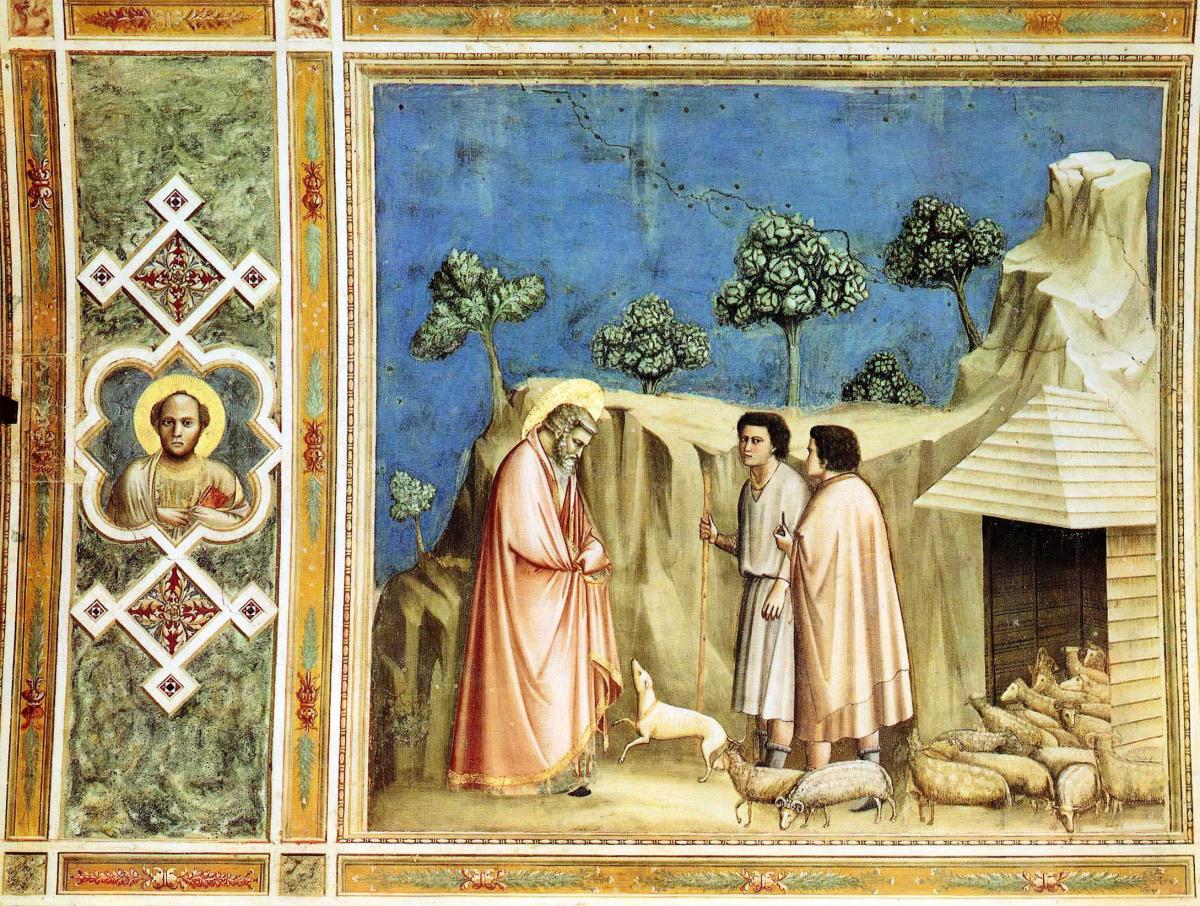

The next scene is “Joachim and the Shepherds.” Joachim fled from Jerusalem for the surrounding mountains to do penance and fast for 40 days in an effort to receive God’s blessing. He greets the shepherds with a bowed head and clasped hands. He has come to purchase an animal for a sacrificial offering. One young shepherd holds a staff and the other holds the coin purse with the payment. A sheep dog comes up to greet Joachim, one of Giotto’s human touches

The scene includes the flock coming from the wooden stable. The space where the figures stand is enclosed by a rocky outcropping. Rising from its top are several green poorly rendered trees. Above this landscape is Giotto’s blue sky, more appropriate in this outdoor setting than in the previous scene inside the Temple. His new-found ability to create depth using light and shadow allows the viewer to experience the possibility of entering the scene.

The next scene, “Joachim’s Sacrifice” (not shown) depicts him sacrificing at the altar, with the hand of God extending from heaven to bless him. In “Joachim’s Dream,” (not shown), an angel appears to him to tell him his prayers have been answered. In the “Annunciation to Anna” (not shown) an angel appears to her as she prays and announces she is pregnant.

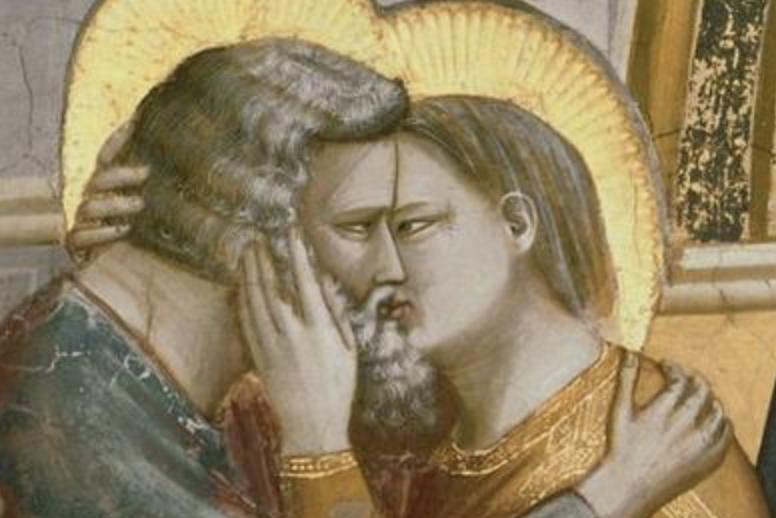

“Meeting at the Golden Gate” is one of the best known and most critically acclaimed scenes in the series. Joachim has returned from the mountains, and Anna has come out to meet him; both are delighted with their news. Giotto painted the couple sharing their joy in a loving embrace and a kiss. His ability to conceive of small and intimate gestures was extraordinary for his time. He struggled with perspective in painting of the bridge, fortified wall, arched doorway, and towers. The Golden Gate is the name of the entrance into Jerusalem, and Giotto paints the arch in gold leaf. Inside the city a group of Anna’s friends await her with joy. The porch of an inner building also can be seen.

“The Birth of the Virgin” (not shown) and “The Virgin Entering the Temple” (not shown) come next. At age three, Mary enters the Temple without fear or reservation. She was educated and raised in the Temple until she was 14, and marriageable.

The story of the “Marriage of the Virgin” as told in the Golden Legend and depicted in the last three scenes of the fresco. An ancient belief held that a child born to an elderly mother was destined for greatness, as a result Mary had many suitors. “The Rods Brought to the Temple” (not shown) depicts a large number of eligible men seeking her hand. It was decided that each would leave his staff on the altar in the Temple overnight. The staff that bloomed overnight would identify Mary’s bridegroom. Joseph, an elderly widower with children, reluctantly left his staff, and it bloomed with a white lily.

The “Marriage of the Virgin” depicts the ceremony in progress. Joseph’s age is indicated by his white hair and beard, and he holds his staff with the white lily and dove. Joachim, Anna, and some friends watch from the right. A group of unhappy suitors is gathered at the left. Only one seems to offer his blessing, while the suitor behind him and wearing a dull red robe, angrily breaks his staff over his knee. The last of the eleven scenes depicts the “Wedding Procession” (not shown) as the new couple are serenaded by musicians.

Having begun the frescoes in story sequence, Giotto improved his technical ability as the work proceeded. The wedding takes place in front of the arch-shaped nave of a chapel. Two transepts are seen from either side. The architecture and the people are not in proper scale, but Giotto’s ability to create a more realistic portrayal of his subjects improved significantly over the course of the project. The task of painting the entire interior of the Arena Chapel was daunting. Giotto well deserves the accolade “father of European painting.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.