Juan Munoz grew up during the repressive regime of Francisco Franco [1939-1975]. Bored with school, Munoz was expelled; a tutor was hired for him and his brother. Fortunately the tutor was a poet and an art critic who covered the usual curriculum, but also introduced Juan to the world of art. He intended to study architecture in Madrid; however, in 1970, he ran away to London to escape the Franco regime and to study. He stated “I traveled a lot and produced very little. Much later in 1982 or ’83, when I returned to Spain, I stopped traveling and finally set up a studio. That’s when I started making objects.”

His early works were of “dwarves, mannequins and ballerinas.” This choice of subject matter reflects Munoz’s self-described sense of isolation and “displacement.” He wrote that he “always felt outside of the main stream.” As a Spanish artist, his choice of dwarves also reflected the seventeenth Century Spanish tradition to keep them as companions to royal children. Portraits of dwarves were frequent. The well known Spanish master, Velasquez, painted several. Both artists portrayed dwarves with dignity and respect, not as pets.

Munoz received a Fulbright Scholarship (1981-82) through the North American Spanish Community to study painting at the Pratt Institute in New York. While in New York City he was artist-in-residence at P.S.1, the New York public school noted for the arts. To earn additional money to support his wife and children, he worked as a waiter. Returning to Spain in 1985, he began to include simple architectural settings for his sculpture figures.

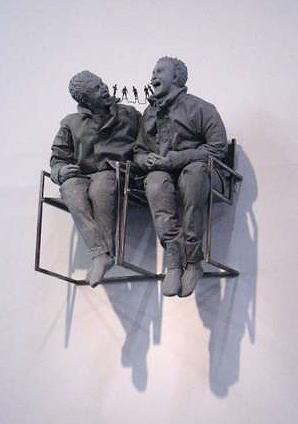

After a 1991 trip to Rome, to study ancient Roman and Baroque architecture, he frequently included architectural settings. Many are distorted settings with bent chairs and benches, falling floors, chairs with his figures hanging from the wall, and in varying scales to create physiological tensions. His human figures, mostly male, are slightly smaller than life-size, all gray in color and wear coats and jackets. Most figures are smiling. What are they smiling about? Munoz arranged the figures in small and large groups, sometimes as many as 50. Viewers are intended to walk among the figures and engage with them. There is always a conversation happening. Munoz is a storyteller, setting up narrative situations.

“Last Conversation Piece” (1994-95) is so named because it was the last in a series of works called conversation pieces. In it Munoz employs a second figure type. The arms and heads are close to reality but the body from waist down is distinctly non-human. They resemble feather pillow or bean bags, but are cast bronze and very heavy. Three figures are grouped together in a conversation which from one point of view looks friendly. One leans in to whisper in another’s ear while giving him a pat on the back. With their big round bottoms they are hilarious and may remind one of Weeble Wobbles, Hasbro Playskool toys, children shaped like eggs but balanced in a way to always remained upright. The figure on the left wants to become a part of the group. Does he simply want to join his friends or does he feel left out, isolated? He seems determined to get to the others, and we image him rolling across the lawn to join the group. Will he make it? The other figure on the right looks on and may or may not feel excluded, and he seems in no great hurry. Munoz often intended to show the “poignant isolation of the individual amongst a crowd.”

Munoz is a storyteller, setting the stage for numerous interpretations. When one walks onto the lawn and actually engages with the figures, new ideas emerge. It becomes apparent that the three figures are not engaged in friendly conversation, but in disagreement. One figure pulls on the other’s robe, and the other, who is patting his companion on the back, now looks surprised. The two other figures have a different dynamic. The attempted movement of the figure to the left now seems more urgent. Is he trying to intervene and prevent future unpleasantness, and on which side is he? The figure on the right remains distant and is as enigma.

Munoz said he was “fascinated by the ‘’otherness’’ of the figure.” He intended the “sense of ambiguity and enigma, in which the boundaries between reality and fiction are blurred, creating an increasingly complex play of contradictions and paradoxes.” He did not intend one interpretation for his pieces, but many.

Munoz realized that his works contained both peace and violence. “The violence had to do with my memory and with my fascination. People who have experienced violence are activated by violence.” Although he does not seem to speak about it directly, the violence he most likely referred to was his childhood in Franco’s Spain. “For years I used to carry a switchblade in my pocket wherever I went. I’d have my hand in my pocket and I would be touching this knife. It was about an inner violence that I always had inside. I eventually stopped carrying this knife because I realized that it was getting a little neurotic, and I shifted to a deck of cards.”

The term conversation is defined as “talking together, informal or familiar talk, verbal exchange of ideas, information, etc.” At this particular time in America, conversations are important, particularly conversations which exchange thoughtful ideas and truthful information. Today we are witness to both peaceful and violent conversations. Munoz’s “Last Conversation Piece” causes us to think about our current situation and our current conversations. We need to be thoughtful, we need find truth, and mostly we need to find reconciliation.

Munoz died suddenly in 2001. He was forty-six. The London Guardian wrote that Munoz “was the most significant of the great generation of artists to achieve maturity in post-Franco Spain, and one of the most complex and individual artists working today. Munoz has died at the height of his powers.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.