Julie Buffalohead’s parents are college professors, and she grew up knowing writers, poets and artists. Her mother is white and her father, Director of American Indian Studies Department at the University of Minnesota, is a Ponca Indian. Although she is biracial, she identifies with her father and says her tribe is Ponca; “I go by what my father taught.” “When I was younger, drawing and being bookish was a way to gain energy.” At five years old she started drawing animaIs, and in school she took drawing classes. “When I got to college, I knew I would do something in arts for the rest of my life.” In 1995, she received a BFA from Minneapolis College of Art and Design. She worked with elementary school students while completing her MFA in 2001 from Cornell University. Her MFA mentor was Kay Walkingstick, a well known American Indian artist.

Buffalohead’s art is a mixture of many elements. Much of her imagery comes from tribal stories she heard as a child: “I’ve always been attracted to trickster characters in Native belief systems because they’re so opposite to Judeo-Christian values. Judeo-Christian tends to be about good and evil, and it talks a lot about how you do this and it’s good, or you do that and it’s bad. And what coyotes and rabbits, who represent tricksters, do is really in the gray. It’s about doing both those things. It’s about having characteristics that make up good and evil, and it’s OK to be a blend of both.” Tricksters “represent to Native people what it really means to be human. It’s not just black and white — you’re many things. You’re all things. I use a lot of characters that are in my tribal stories, adding in a little bit of chaos, a sort of homage to my Native upbringing. “

Her paintings are generally small, ranging from 20 to 30 inches, and her painting style can be described as delicate. “I’m a perfectionist; I have this battle in my brain about what I’m making and translating and how it looks aesthetically. Being an artist is like being a writer. You pre-write and write and edit and edit again.” She describes her imagery as “so personal it’s hard to think about the viewer, but I try to be provocative. I use stereotypes because Indians didn’t have a hand in creating them. It’s my way of saying ‘this is not who we are.’ This is your invention.” According the Buffalohead, Indian stories are passed down from generation to generation. Each person who inherits the story changes it. Interpretations of her painting are left up to the individual whether they know the stories or not. When this article gives a meaning to the many Native American figures, they are compiled from several reference sources.

Buffalohead grew up in a suburb of Minneapolis with familiar American toys, TV shows, movies, commercials, news and politics of the time. “Are you the Good Witch of the Bad Witch? (2010) [20’’X30’’), illustrates her mixing of Indian and American themes. Glenda the Good Witch, a character from the “Wizard of Oz,” holds up her hand to stop Coyote and to question his intentions, much as we might do to those different from us. With her are the identifiable toys of childhood: a Ninja Turtle with a weapon, Elmo, Sponge Bob Square Pants, Hello Kitty, a plush rabbit, My Little Pony and two cupcakes. These American icons may need protection. Coyote walks upright like a human and holds a broom representing the American idea that witches fly on them. With him are a fallen Snoopy holding an assault rifle, a yellow toy dump truck, a Star Wars All Terrain Armored Transport and a Smiley Face white cylinder; not toilet paper. All of her images intentionally appear as children’s story illustrations. She sends her message to us in a soft and non-threatening way. However, the message is clear. It is easy to jump to conclusions about people who don’t look like us or act like us.

“If You Make this World Bad and Ugly” (2014) (25’’ x 37’’) portrays another of Buffalohead’s themes. American Indians, as do many of us, seek to preserve nature and the environment. A Lakota creation story tells that the creator made the world twice and destroyed it twice because humans were not acting as humans. Buffalohead suggests in this work that the world may need to be destroyed and remade once again. Otter represents female energy and is balanced between water and earth. Otters are seen to be playful and joyful. They approach strangers from curiosity and friendship. They will never attack but will defend. Otter is playing with a silhouette puppet of a suited man. With Otter is Turtle, who represents the story of creation. Turtle was the first to reach land from the water and carries the new born earth on its back. Rabbits are fearful of almost everything, and it is the Native belief that you are always the cause of what happens to you. Owls have second sight and can see in the dark and the light. They are the essential image of wisdom. Geese fly south during cold weather. These animals all sense something is out of balance. Oil wells loom across the entire background. Fossil fuel is endangering our climate.

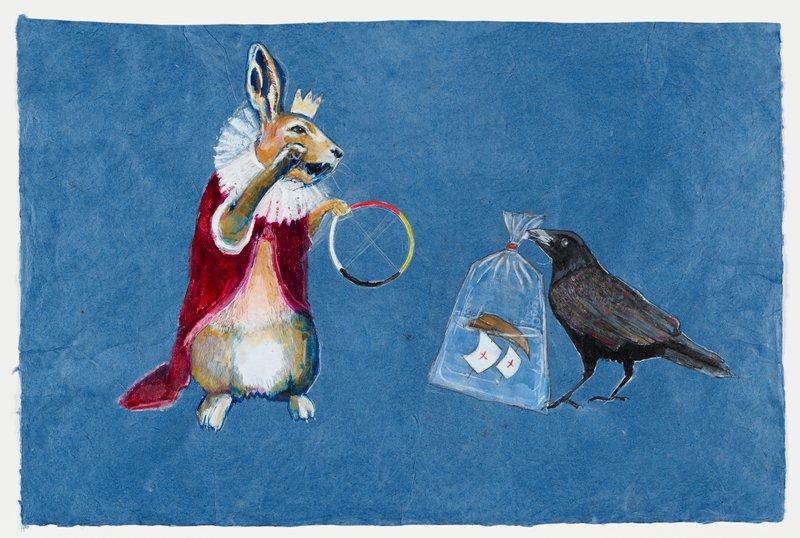

Native Americans were displaced by Europeans conquerors. “Queen Isabella” (2014) (13.5’’x 30.25’’), reminds us of how this process began. Ravens are magical and are thought to be messengers. Their feathers are iridescent and therefore appear to change color and shape, revealing both outer and inner truth. They are said to give a person courage to change their outlook and go fearlessly into the future. Raven reminds us of carnivals in our childhood when we caught gold fish and brought them home in a plastic bag filled with water. He has captured the Santa Maria and holds it closed in the plastic bag. Queen Isabella is a large fearful rabbit and does not want to take the boat in the bag. She is not changing her outlook. She holds tight to a medicine wheel meant to protect the owner. The medicine wheel has four cross pieces representing north, south, east and west. The medicine comes from the four directions which multiplies this gift. Four colors form the wheel. Each color represents the great power possessed by of eagles. Yellow is the eagle of the east and represents the far sight of the east. Red is the eagle of the south and he is far sighted and innocent of heart. White represents the eagle of the north and his far sightedness derived from the ancient knowledge. Black is the eagle of the west whose far sightedness comes from introspection. Isabella holds tight to the medicine wheel for her protection. Ironically it is the Indian population of America that will be decimated by European disease.

Julie Buffalohead’s work illustrates many other themes as well. Using her children’s illustration style she depicts her personal feeling of inadequacy. She uses disguises, usually as a coyote in a dress, to be able to speak for her. She holds Coyote as her personal symbol. Her titles are indicative of these memories of childhood. “Tea Party One”, “Tea Party Two”, and “Tea Party Three” (2008), “Dress Up” (2008), and “Mine” (2005). Examples of various themes include “Turn a Blind Eye” (2014), which speaks of domestic violence; and “You are on Indian Land” (2017), is political and refers to the Dakota Pipeline. There is also “Why I Hate Bras” (2018).

She still is a young working artist with much to say to us. “I’m interested in all the philosophy and the things that go behind these stories. I use them as guide and way to tell my story. Every person who inherits the story changes it. So you end up with very different stories than when you began, but you still maintain something about the worldview that remains the same.” In a 2019 interview she was asked her thoughts on the current state of Native art: “I wish we would start seeing Native artists represented internationally.” She is referring to contemporary Native Art which are“not often given the chance, because people want to see Native people as part of the past.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.