As a child, Walton Ford (b.1960, Larchmont, New York) spent time hiking and fishing in Canada. Using binoculars to see details, he began to draw animals. He received a BFA at Rhode Island School of Design in film making (1982), but after a senior year spent in Italy, he became a painter. An avid reader of history, folklore, and mythology, Ford uses this knowledge to create life sized images to comment on the treatment of animals. His choice of watercolor as the medium is consistent with the painting of natural history subjects introduced in the watercolors of Albrecht Durer in the early 16th Century. Ford stated, ’It was very important to me to make them look like Audubon’s, to make them look like they were a hundred years old.”

In 1995 Ford’s wife received a fellowship to study tantric art in India. The family, including their one-year-old daughter, lived there for six months. At first Ford was daunted by the experience, but he gradually began to realize that the thousands of years of history and culture had something of great importance to teach him. He started to study the histories of animals and their treatment. “Nila” (1999-2000) (144”x216”) depicts a large male elephant, head held high, striding across a flat landscape. Nila is not the name of the elephant; nila in Ancient Sanskrit are the elephant’s nerve centers. The elephant trainer uses these pressure points to direct the elephant’s movement. Like African elephants, Indian elephants are sought after for their ivory and are on the critically endangered list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (INUC).

In Ford’s painting, several kinds of birds act on these nerve centers. Rather than ox-peckers, who eat ticks from the elephant’s skin and are helpful, Ford includes in the painting starlings, goldfinches, a woodpecker, and other western birds that annoy the elephant. According to Ford, the starlings represent Western tourists. European starlings are considered pests; they are aggressive toward other birds and are known to force them from their nests. They eat enormous amounts of fruit and grain intended for human consumption, causing plants to become diseased. European starlings are designated as an invasive alien species in North America. The goldfinches that plant flowers on the flat landscape represent Peace Corps volunteers, and the woodpecker represents Westerners who shop in India.

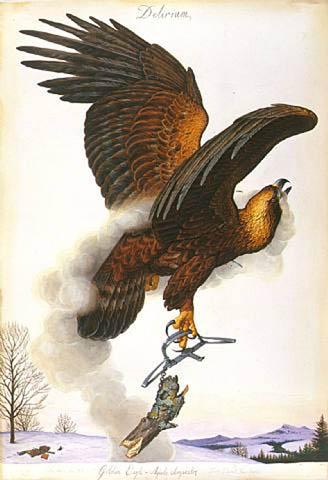

“Delirium” (2004) was influenced by John James Audubon’s description of his painting of a golden eagle. Audubon’s The Birds of America (published 1827-1838) contained 435 life-sized prints. Ford’s animal paintings are intended to maintain the Audubon look, including the fine detail and scripted titles. Audubon did not paint living birds. He wrote that a golden eagle had been caught in a fox trap by a farmer, and the eagle carried the trap for more than a mile until it no longer could fly. Audubon bought the live eagle from the farmer and tried to asphyxiate it with burning charcoal and sulfur: “I was compelled to resort to a method always used as the last expedient, and the most effectual one. I thrust a long-pointed piece of steel through his heart, when my proud prisoner instantly fell dead. I sat up nearly the whole night to outlive him. I worked so constantly at the drawing it nearly cost me my life. I was suddenly seized with a spasmodic affection which much alarmed my family. The picture of the eagle took me 14 days. I never labored so incessantly.”

In “Delirium” Ford represents both the eagle’s and Audubon’s delirium. Smoke surrounds the eagle as it flies, dragging the trap. The sharp metal pin projects from the chest. The small figure of Audubon is crumpled on the snowy ground at the lower left corner of the painting.

“Condemned” (2007) (21.4’’x15.75’’) (6 copper plates, etching, aquatint, drypoint print) is an image of the Carolina Parakeet, the only parrot indigenous in the Eastern United States. It was declared extinct in 1939. Ford’s print depicts the richly colored bird as it is enjoying a ripe, juicy peach. Audubon warned in 1831 that large flocks of this magnificent bird were declining: “In some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are to be seen.” The loss of habitat created some of the problem, as large areas of forest were cut down for agricultural use. Farmers, who considered the birds pests, shot, and poisoned thousands of them. Their beautiful feathers also were prized as decoration for ladies’ hats. Disease was another cause of the demise of the Carolina Parakeet.

Flowing from the Carolina Parakeet’s mouth is an inscription: “I wish that you all had one neck, and that I had my hands on it.” Ford’s concern for the treatment of animals and the environment is evident in all his work. However, as he says, “I think that there’s almost no subject that you can’t treat with some humor, no matter how brutal it can seem.”

“An Encounter with Du Chaillu” (2009) (95.5’’x60’’) references Du Chaillu, a 19th Century anthropologist, who wrote about and frequently told his story about being the first white man to see a gorilla. While in Africa in 1875, he encountered a large gorilla that was trying to tear down a berry tree. The New York Times (1875) reported Du Chaillu’s talk: “The creature advanced toward him with fierce yells, beating his huge breast with his fists until it sounded like a drum, and evidently was not in the least afraid of the four men. Du Chillu did not fire until the gorilla was within twelve feet of him, and then he shot him through the heart, so that the creature fell dead before him on its face with a human-like groan.

Ford adds his spin to the Du Chaillu’s story. The giant gorilla stands upright. It has broken the barrel of the rifle. Its licks the end of the barrel with its red tongue to see what it tastes like. Ford places a pair of human legs in the ground cover at the lower right corner of the painting. It looks as if the gorilla has won this round, another of Ford’s humous twists on what is otherwise a sad, but true story. In the wild the only danger to gorillas are leopards. Gorillas are killed by poachers for bushmeat that is highly desirable among the wealthy. All gorillas are on the endangered species list of IUNC. The loss of habitat, disease, and poaching have reduced the current population of mountain gorillas to a little over 1000.

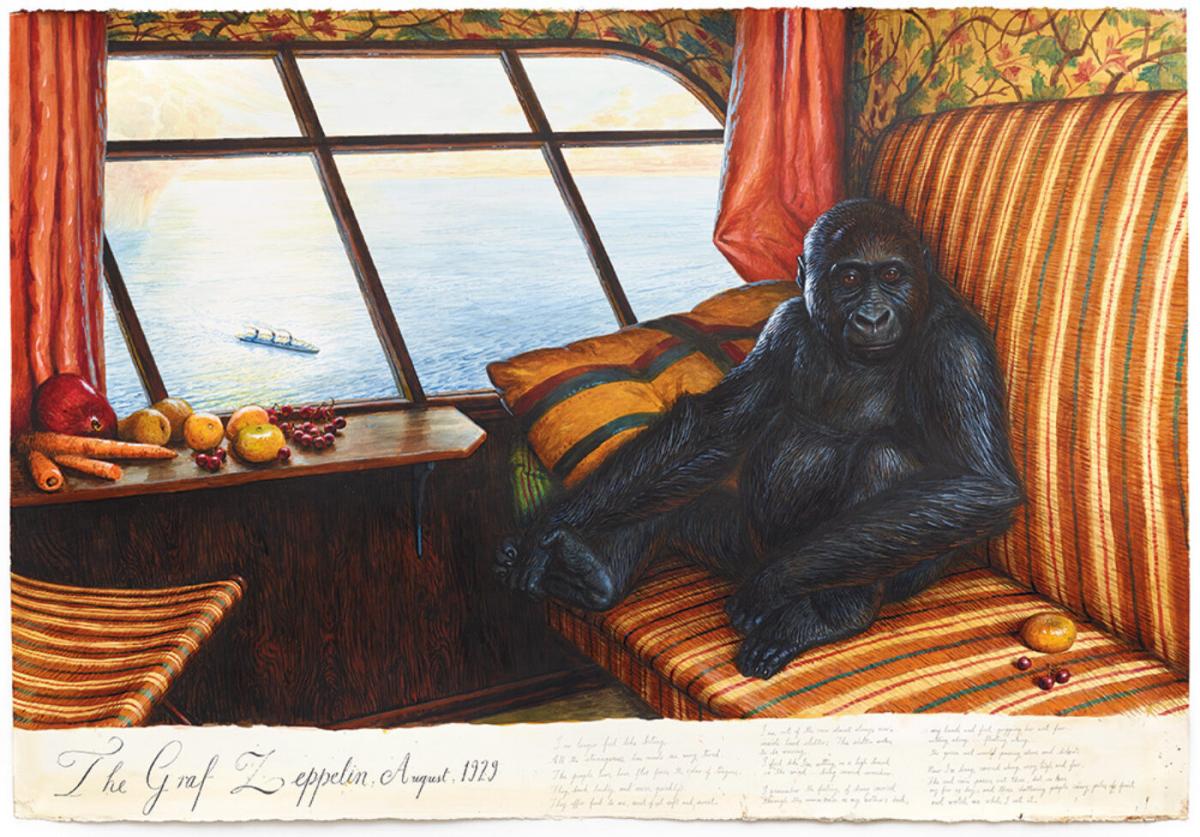

“The Graf Zeppelin” (2014) (41’’x60’’) tells the true story of Suzie, the first female gorilla brought to an American zoo. Suzie was flown in 1929 across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City in the first-class cabin of a German Graf Zeppelin. Ford depicts Suzie in the comfortable first-class cabin with floral wallpaper, red curtains, cushioned seats, and a pillow, all color coordinated. A table is set with assorted fruits and vegetables for Suzie’s snacks. A wide window overlooks the ocean, revealing a steam ship cruising below. The window and the cabin take up three-quarters of the composition. The depiction of Suzie, sitting up-right, takes up about one-quarter of the painting. Her dark coat contrasts with the bright colors of the cabin. She makes eye contact with the viewer.

Ford commented on Suzie: “She didn’t bite or kill anybody. She’s doing that survival thing of traumatized victims of war and refugees. Suzie, the Graf Zeppelin gorilla, lived to be about forty in the Cincinnati Zoo. That’s it. A few sentences in some magazine article I read, you know? But I’m like, what does that mean? Jesus, what a journey! What was her life like? This is the beginning of a huge story for me.” Ford imagined Suzie’s thoughts, her confusion, and her fear, and he inscribed them on the painting.

Ford’s work is exhibited around the world. He has depicted both the glory and horror of the natural behavior of animals in the wild, their encounters with explorers and hunters, and imaginary animals described in myths and folklore. Recent work includes a triptych of the tar pit “La Brea” (2016), a series on animals of California (2017), and a series on the Barbary Lions from the Roman colosseum to the MGM lion in “Ars Gratia Artis” (2017). A 2022 exhibition of work based on images from the journey of the 16th Century Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca, who was shipwrecked in Florida. His claims include killing the last great auk, a member of the flightless penguin family.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.