I look at the way we treat each other and I think to myself that the world has gone mad.

History, however, suggests that the world’s always been mad. It’s just that today some changes have made our insanity more lethal.

Regarding danger, two things in particular have upped the ante; global access to electronic communication and sophisticated armaments. The outraged loner, the suicide bomber and child soldier of Africa, the religious zealot, street gangs and rogue causes of every description can easily arm themselves with modern weaponry, frequently made in the USA. They spill rivers of blood and communicate secretly, all with impunity. The intentional killing of noncombatants as the preferred battle strategy is a glaring testimony to how little basic moral parameters constrain behavior in the postmodern world. Winning is everything; it’s “no holds barred.” It’s as though we’ve returned to the caves.

Americans have historically enjoyed safety in tumultuous times unlike other industrialized nations. In the last century through two World Wars, the Korean and Viet Nam conflicts, our homeland remained a comparatively safe place.

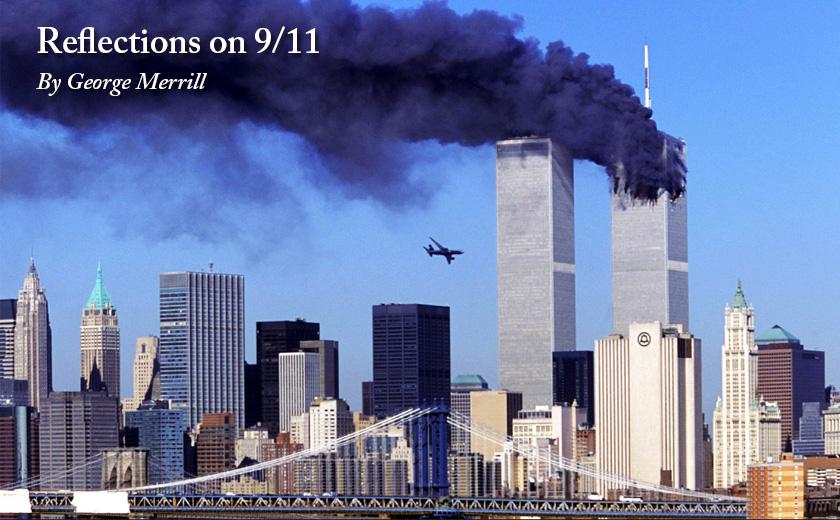

On 9/11, in Shanksville, PA, Washington, D.C. and New York City the illusion of our invincibility went up in flames. We watched on TV to see the Twin Towers fall, saw the destruction of part of the Pentagon and the wreckage in a hole in a field of PA where a forth plane crashed. We, too, fell from innocence and joined the ranks of most of the world’s nations in feeling the wrath of war exploding on own doorstep.

The attack invoked personal and national sorrow, humiliation, rage, calls for retribution, and finally became the prime motivator for the first Iraqi invasion. In an atmosphere of fear, rage and humiliation, good decisions are rarely made and to this day the wisdom of the invasion remains dubious. In our efforts to cast out the demons that plagued us, we took on more devils and our last state of affairs became worse than our first.

9/11 launched the reign of terror that has become the standard preoccupation in global conflicts and fear has taken the place of reasonable ideas and inspiration in our present international and political debate.

In an article I read recently, a journalist interviewing in Louisiana takes notice of a truck parked nearby him. The truck is red and on the side is a picture of the Statue of Liberty. In the hand of Liberty’s raised arm, instead of the torch of liberty, she holds an AK47 assault rifle. America’s welcoming lady is presented as an armed guard, changing the entire meaning of what she stands for.

I believe what is great about America is represented by the Statue of Liberty. It is a modern symbol of an ancient and tribal code- the code of hospitality. Once the stranger enters your tent, he is extended hospitality and kept from harm.

The irony in the immigration debate is, of course, that except for Native Americans (who turned our to be far more hospitable than the European migrants whom many helped settle) that in the States today there’s no ‘pure American.’ We are the world’s signature hybrids, mutts, if you will. We were all once strangers in the land. Some indigenous peoples welcomed us and helped us build a life in what was then known as the new world. Donald Trump’s claims to Make America Great Again, is a ruse: immigrants flock to the States because, unlike Trump, they see just how great America is already. A lovely land is an invitation to live there. And the reason we are great has nothing to do with how much strong-arm muscle we can flex, but how our arms have the divine capacity to embrace the stranger and keep him from harm.

In 2000, a dear friend, Father Jack Sullivan (Catholic priest, Irish but very nice considering he’s from an immigrant family) and I, both native New Yorkers and clergy, returned to the city for a sentimental journey. He and I were both ordained in 1960; Jack at the Maryknoll Seminary on the Hudson, and I at St. John the Divine in Manhattan. He grew up in Queens and I on Staten Island. His ancestors came from Ireland, and mine from Warwick, England.

We took the ferry to Bedloe’s Island, now Liberty Island, to have lunch, enjoy an overview of the city, and swap stories about our city childhood. While we had lunch, Jack told me this story.

He’d returned after years in Hong Kong to his home parish in Queens. He’d been invited back to celebrate mass. The neighborhood, once predominantly working class Irish, had begun changing to become predominantly Hispanic and Haitian. One of the old Irish parishioners served as acolyte for Jack at the mass. As they were vesting in the sacristy, the elderly Irishman leaned over to Jack with a look of solemnity and with an Irish brogue as thick as paddy’s pig, said conspiratorily, “Father, you know it’s not like the old days in the parish, anymore. They’re mostly foreigners now.”

Faith and begorrah, now, doesn’t that say say it all?

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.