I am writing this essay on Sunday morning, November 1st, All Saints Day in the Christian calendar and two days before the election when America chooses its next president.

I would describe my feelings that day in this way: it’s the kind of anticipation I remember having as a boy on Christmas Eve. I knew exciting things were on the way and I could hardly wait for the day to come. However, now there’s a new rub. On Christmas Eve, I was always sure it was Santa who’d come down the chimney. On Election Day, I fear it might be the Grinch.

It may seem odd to some that I entertain Election Day and Christmas morning in the same thought. It’s not as quirky as it first appears. Consider, that for many people, both events are significant communal experiences involving the entire nation, if not religiously, certainly socially. In one sense, Election Day and Christmas Day have this in common: it’s a time when we finally learn what’s been wrapped up and hidden, or, in election parlance, the ballots are unpacked, counted, tabulated and the results made public. We open up on Election Day what has been wrapped and kept from us, like the Christmas presents that sat unopened under the Christmas tree.

There are other ironic parallels to the social experience of Christmas morning and Election Day. It’s the common experience of people, when getting what they say they want, to find fault with it. They soon feel cheated. They complain it wasn’t what they really wanted after all. This is why stores, the day after Christmas, never sell a thing; they only exchange. On Election Day, what we get is like a sale item; there’s no taking it back or exchanging it for a long time. That makes people mad.

I suspect this kind of disappointment happens a lot more in elections than with Christmas presents. I hear people complain regularly that politicians are all liars and not to be trusted. In saying that, I think I must also own the fact that there is nothing as fickle as the American electorate. A blog called, ‘The Fickle Finger,’ announced giving its, “2016 Fickle Finger of Fate Award” to the American electorate. It was the tenth year in succession that only fifty to fifty five percent of Americans turned out to vote in the presidential elections. This recognition was not meant to bestow honor on the electorate. The number may be greater this time around.

Americans complain loudly if they think their rights are being taken away. They’ll get mean if they think they are being denied any of them. We demand our rights, but even having them we fail to exercise some of the most important ones, like voting. I think of such people like the kid who wants straight ‘A’s in school, but never does any homework or studies. Still, he faults the teacher who flunks him. American citizens have trouble showing up: We take our blessings for granted. Americans are also embarrassingly ill informed.

I confess I was feeling very nervous in anticipating how this election might go. An aura of uncertainty, even fear, has characterized the experience for me and for many; it seemed as if the president himself was working hard to stir up confusion during the election. How odd, I thought, from the very person who is supposed to champion and assure the optimum conditions for Americans in exercising their rights.

I have a book I’ve looked at over the years, particularly on mornings when I have sought inspiration for the day. The book is about saints. The saints have been selected from a broader base than sectarian hagiographies normally choose. The author’s intent was not to showcase a gallery of stained glass saints, colorful but remote. He wished to present us with stories of authentic human beings “endowed to awaken that vocation in [us] others.”

For each of the year’s 360 days, there’s a brief sketch of one saint’s life and work. It names saints we’re familiar with like St. Mary or St. Francis, but also people whom we don’t normally think of as saints; historical figures like Dag Hammarskjold, Dorothy Day, artist Vincent van Gogh, the prophet Moses, and George Fox, the founder of the Quaker movement.

I couldn’t resist an impulse to look and see what saint the author selected for Election Day November 3rd. I will own, being nervous as I was, that I was indulging in some magic thinking, hoping for a sign from heaven that would signal, when the election was over, that all would be well.

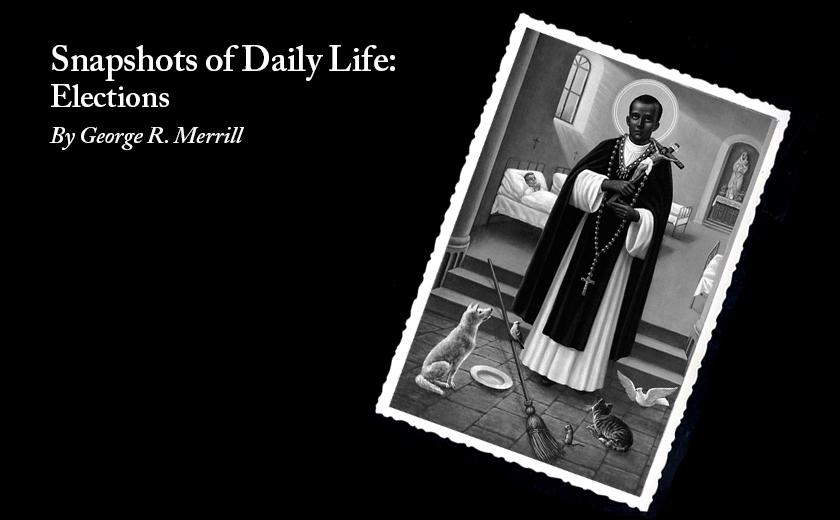

The saint profiled for that day happened to be St. Martin de Porres, a 16th century, mixed-race Peruvian. Martin’s bi-racial profile –– African and Peruvian –– placed him in the culture’s social “minority,” its underclass. Dirt poor, profoundly humble, he exhibited great compassion for all living things and, like St. Francis, had a mystical relationship to nature, even to the most humble of creatures like the mice that plagued the monastery. Martin had an extraordinary gift for healing. He healed noblemen, as well as slaves and other disenfranchised folk. He made diseased animals well again.

If I could have it my way, I ‘d like the person we elect as our next president to have at least two of those characteristics: a heart for compassion and the gift for healing and reconciling. We are, after all, a deeply wounded nation, hungry for healing.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.