Bet you didn’t know the Waterfowl Festival, which would have been celebrating its 50th anniversary this month but for a pandemic, traces its roots back to an outlaw culture, not unlike that of bootleggers of the Prohibition era.

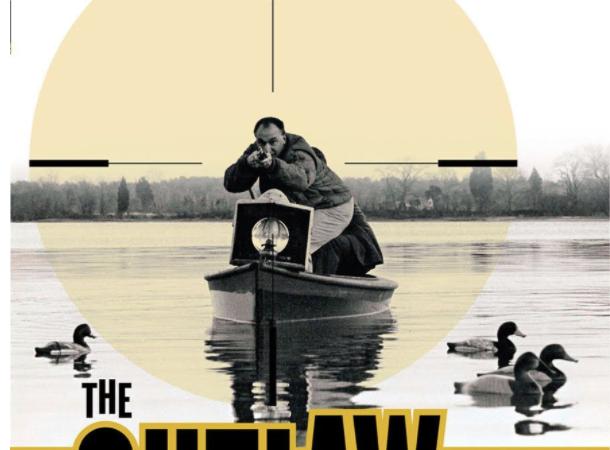

Harry Walsh, who died in 2009 at the age of 85, was for many years an Easton doctor, surgeon, and healer who often accepted oysters and duck decoys as payment for his lifesaving and life-giving services. “He was owed millions, but got all that back and more in friendships,” says his son, Joe, who recently moved to Tilghman from Annapolis. He has put together the second edition for release this month of his father’s bible of waterfowling, “The Outlaw Gunner,” subtitled “A Journey from Hunting for Survival to a Call for Waterfowl Conservation.”

Walsh was a co-founder of the Waterfowl Festival, which launched in 1971. Born in 1924 along the Chester River in Chestertown, Walsh came of age during the Great Depression. It was a time when men learned to find the next meal for themselves and their families by bending nature and its wild bounty to their will and wiles. In communities up and down Tidewater country, from the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, watermen devised more efficient and deadly ways to “harvest” ducks–to kill them en masse whether flying overhead or landing in baited fields or amid a decoy flotilla just offshore.

Walsh was a co-founder of the Waterfowl Festival, which launched in 1971. Born in 1924 along the Chester River in Chestertown, Walsh came of age during the Great Depression. It was a time when men learned to find the next meal for themselves and their families by bending nature and its wild bounty to their will and wiles. In communities up and down Tidewater country, from the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, watermen devised more efficient and deadly ways to “harvest” ducks–to kill them en masse whether flying overhead or landing in baited fields or amid a decoy flotilla just offshore.

In their heyday, especially during the Depression and the prolonged recovery that didn’t reach anything like prosperity until the close of World War II, these men–known as “market gunners,” were regarded as upstanding citizens in their hometowns. They fed more than their families. They helped feed their neighbors and supported their communities with the wholesale marketing of their excess haul of slain birds. In his book, Harry Walsh quoted Mrs. Sophie, whose inn took in hundreds of ducks a season, “Lord, seems I stay in blood and feathers all winter long. Ain’t no sin to be poor, but it sure is unhandy.”

Restaurants in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York–as well as millionaires who threw lavish parties–ordered ducks and geese by the hundreds a weekend.

To meet the demand, market gunners–as opposed to sport hunters–invested in the latest and deadliest artillery, as well as baiting and decoy techniques that led to quick and massive kills.

One of the most warlike weapons was the punt gun. Weighing 100 pounds or more in a teetering skiff skimming low in the water, it snuck up on floating congregations of ducks at nightfall. With a half-pound of powder and 10 barrels of gunnery, a boatload of men could blow 200 to 300 hundred ducks out of the water each night.

“It was horrible,” Joe Walsh says. “Ducks used to fill the sky like bees. They’re coming back, but only because of conservation.” Translate: enforced limitations on bird kills.

Unlimited hunting became illegal in the late ‘30s, and market hunters tried to adapt. While their faces were not on wanted posters, they risked being handcuffed by game wardens and fined a week’s worth of dead-duck income or imprisonment for failure to pay such fines.

“My father saw what was happening to the environment that had supported generations of hunters,” Walsh says. As a physician, he espoused stewardship of wildlife and the natural world he grew up in.

Still, he loved hunting. “Good hunting companions are a treasure,” Harry Walsh wrote in his book. “They are a lifetime in the making.”

The second edition of “The Outlaw Gunner” introduces two chapters of Walsh’s unpublished “My River,” as well as a pair of forwards by Pete Lesher, Talbot County councilman and chief curator of St. Michaels’ Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, and Henry Stansbury, maritime museum vice-chair.

Walsh’s first donations of his collection–mostly decoys and hunting guns–went to the maritime museum at its 1965 founding. Decoys later anchored the artistic aspect of Easton’s inaugural Waterfowl Festival.

Duck decoys, while less aggressively deadly than guns, played an essential role in both sport and market hunting. Typically, carvers were not primarily hunters. They specialized in carving realistic likenesses of canvasbacks–among the earliest to be protected due to over-hunting–black ducks, redheads, and sprigtails, among others. To the extent that hunters participated in creating decoys, it was in training live birds to play the role of killer lures. One such legendary decoy, a goose, was dubbed Old Pete.

These days, art-object wood carvings aren’t meant to be cast into the water. Their shelf life is literally that. They exist on display in art galleries or the homes of collectors.

In the absence of an in-person Waterfowl Festival this year, your best chance to appreciate the art of decoys and maritime scenes in oil or watercolor is through the virtual art gallery organized by Waterfowl Festival, Inc. While you can’t see the art displayed in galleries or festival tents, nor can you meet the artists in person, you can check out their works online. “It’s our way of connecting art collectors to the artists they love,” says Margaret Enloe, festival executive director, “some of whom,” she adds, “are struggling in this time of COVID.”

As for next November, Enloe says, “We have plenty of time to get it done.”

That will be the 50th Waterfowl Festival because this year’s golden anniversary event isn’t happening. “Masks or no masks,” a masked Enloe told us, “we’ll figure it out by next summer.”

Steve Parks is a retired Long Island arts writer and editor now living in Easton.

Online sales by individual artists indefinitely through waterfowlfestival.org. Release of “The Outlaw Gunner,” second edition, November 2020,

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.