It is tough to put into words, some forty years after the fact, the impact that Libby and Douglass Cater had on the Eastern Shore.

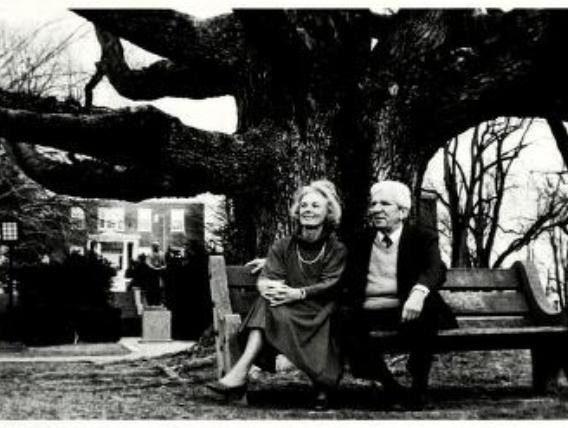

Unexpectedly showing interest in becoming the president of Washington College in the spring of 1982, Douglass and wife Libby stood unnoticed in the crowds who had gathered along Chestertown’s High Street to celebrate the bicentennial of the school that year. According to both, it was love at first sight with both the college and its community.

In many ways, they were the exact opposite of what Washington College and the Eastern Shore had come to expect would lead the small liberal arts college in Chestertown. While the school had a history of superb academic leaders over its 200 years, the appearance of this very sophisticated couple in Kent County was both a shock and a wake-up call; not only with the sometimes sleepy faculty and administrators but for the entire Eastern Shore region. There was going to be a significant change taking place in Chestertown.

Coming on the heels of that town-gown birthday party, the power couple, complete with resumés that included senior roles in the Johnson White House but also prestigious positions at Wesleyan, Stanford, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Aspen Institute, and the London Observer, had come to reside in the historic the Hynson-Ringgold House relatively late in their careers.

In fact, some in the Washington College community were a bit fearful at the time that the Caters, in their late fifties, had agreed to take the job to “feather one’s nest” before decisively retiring. With Chestertown conveniently located within a comfortable driving distance from their Washington base, it was more than possible, at least to some, that Douglass and Libby would simply “phone it in” for the duration of their tenure.

As it turned out, nothing was further from the truth. The Caters, quickly grasping the significance of Washington College, and its special place in the history of higher education, would make this sadly underfunded school their last cause after a lifetime of causes.

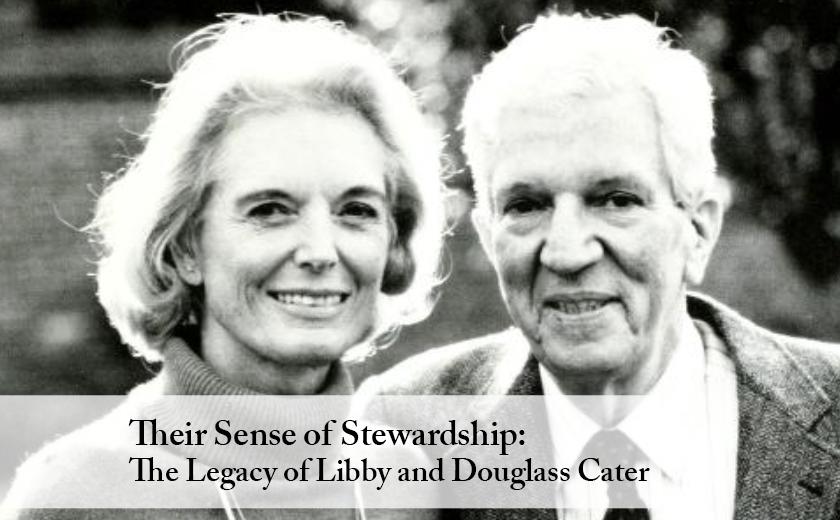

And it was a joint decision for the couple. While Douglass took on the formal title of president, it was a Libby and Douglass Cater enterprise from the get-go.

Our culture sometimes remains fixed on the idea that only one in a couple is expected to take credit when things go well. But from my vantage point, while serving as an administrator during the Cater years, it was clear that Douglass, despite his impressive resumé and education, could not have had any significant achievement in life without his extraordinary collaboration with Libby.

There was little to doubt about Douglass’s intellect, determination, or ambition, but he was also a remarkably pugnacious fellow. Indulged by a family and nurses as a child battling life-threatening rheumatic fever in the 1930s, when the only known cure was for the patient to be restricted to a bed for one or two years, he learned early on that one’s needs could be met by simply shouting his requests from his bedroom. And those characteristics would remain part of his modus operandi for the rest of his life.

A clip of Douglass in action when he testified at a United States Senate hearing on the high costs of private higher education is a stunning example of that grit and determination. It serves as testimony of his raw and relentless fashion even if taking on a powerful, high-ranking public official like Secretary of Education Bill Bennett at the time time. Here is that outtake on Youtube.

Nonetheless, without some sort of balance, Douglass Cater’s most remarkable achievements would have simply been lost opportunities without Libby.

By the time they met, not in their native Alabama but as two ambitious young people working in Washington, it could have been seen as a very odd match from afar. Douglass, relatively short in height, with a disproportionately-sized head on top of a very modest frame, was already at a severe handicap when he set his sights on Libby.

And adding to that list of liabilities was that he was a product of Montgomery, rather than the more sophisticated Birmingham, where his future wife was born and comfortably placed in that city’s well-established society. It is a well-known fact that in Alabama, those who reside in Birmingham, the New York City of the state, could look down their nose a bit on those raised in the state’s capital.

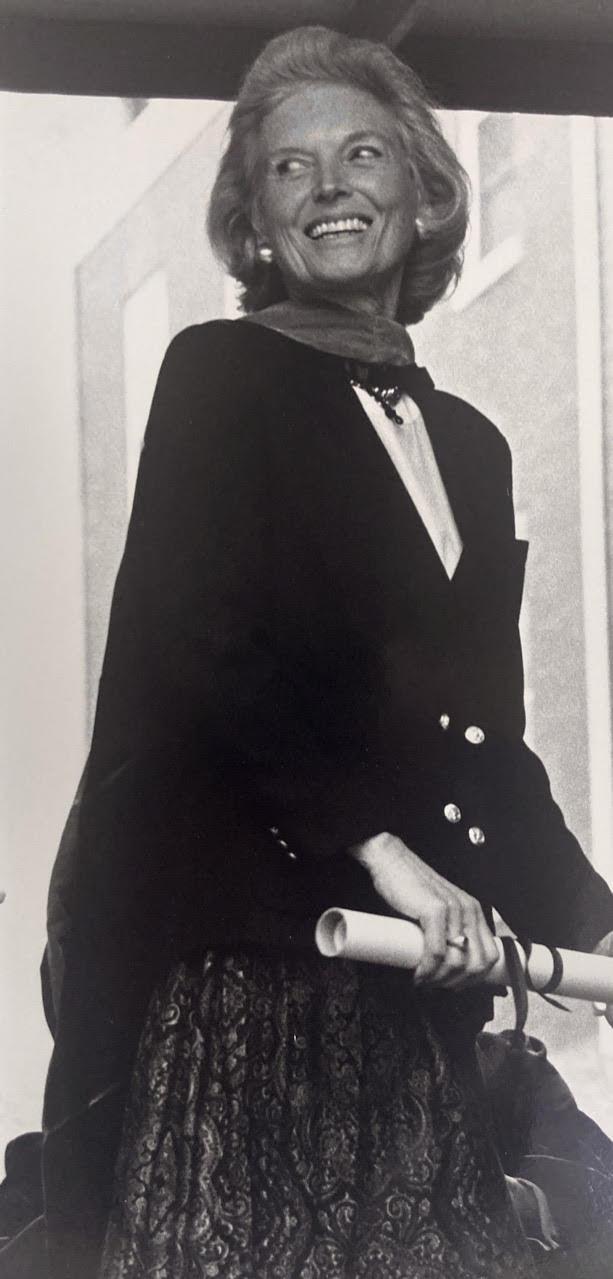

But far beyond these disadvantages was that Libby, naturally blonde, slender, and standing 6 feet tall, was not only stunning but already a player in state politics well before she arrived in Washington. To the shock of many, she became the first woman to be elected student body president at the University of Alabama. For context, it is helpful to note that this SGA role was long considered an important stepping stone in becoming the state’s governor.

It remains a mystery to understand why couples do in fact become couples, but when I look at this early union of Libby and Douglass, it’s not hard to guess that they both realized they had all the “right stuff” for a spectacular life together.

And so they became a team. While this was first seen in Lyndon Johnson’s administration, this union became even stronger when LBJ announced he would not run for reelection in 1968. They moved on to Palo Alto, London, and eventually, to the shock of both the Caters and the citizens of Kent County, to the banks of the Chester in 1982.

With traditions and habits coming from their years at the White House, the Caters set a pace and climate never before seen on the Eastern Shore. Not only was there a new sparkle at the presidential home on Water Street, but locals couldn’t do enough to get an invitation to attend one of their functions.

The Caters intentionally made it a point to blend their large Rolodexes of Washington power friends with the best and brightest of the Mid-Shore. Over time, such iconic A-list powerhouses as Lady Bird Johnson, Bill Moyers, Ben Bradlee, Art Buchwald, and Roger Mudd were co-mixed with the likes of Chestertown’s Constance Stuart Larrabee, Princess Anne’s admired country lawyer Sandy Jones, Cambridge novelist John Barth, Queen Anne’s County’s Nina Houghton and Art Kudner, Talbot County’s Tom Wyman, Augie Belmont, or Bill Brogan. Nor was there any hesitation in pairing the likes of Queen Anne’s County’s beloved superintendent Harry Rhodes or Salisbury University’s legendary lacrosse coach Charlie Clark with such political rock stars as Maine’s Ed Muskie, Treasury Secretary Bill Simon, and Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

For Douglass and Libby, this was not some kind of kumbaya moment for the fellowship of humanity. It was a raw, calculated effort to unite these strange bedfellows in the common conviction that Washington College was one of the country’s most interesting, vibrant, and charming liberal arts colleges. For eight years, they begged, pledged, and more than a few times, would embarrass themselves in this relentless campaign to raise the school to what Douglass called “the higher orbit” of national recognition.

And given this unusual use of what is now called “social capital,” one needs to ask, what did the Caters get out of this exhausting effort? In short, not a damn thing, at least not in the material sense. Surely, money was not the goal. And there was nothing to be gained by their association with a struggling, isolated college, after gigs like the White House or Aspen. In fact, one suspects that their career choice might have been considered a step down given the arc of their experience.

The truth was that they both had a profound sense of mission to rescue and build up Washington College because it deserved it. From the moment Douglass announced during his inaugural address in that the new college administration’s goal was to save this remarkable endangered species, they teamed up to make that happen.

The truth was that they both had a profound sense of mission to rescue and build up Washington College because it deserved it. From the moment Douglass announced during his inaugural address in that the new college administration’s goal was to save this remarkable endangered species, they teamed up to make that happen.

Douglass, never reserved in asking for what he wanted, had no problem in the middle of a pleasant dinner party at Hynson-Ringgold to ask one of the unspecuting guests for a $1 million donation. Beyond the pregnant pause this would create around the table, it was then Libby’s job to somehow smooth out the edges of the “big ask” and remind the prospective donor of how they would have so much impact on not only the students but democracy itself.

This teamwork had remarkable results. And without question, the finest example was Eugene B. Casey and his Washington College alumna wife, Betty. A man who owned much of the land between Washington and Baltimore for most of the late 20th Century, including hundreds of Giant Food Store locations, Casey found the Cater case for support for Washington College so compelling that he and Betty would contribute over $25 million to the school over their lifetime, which is the equivalent of $100 million in 2022 dollars.

But it didn’t end there. Over time, the Caters would win over the likes of Henry Beck, the Texan multi-millionaire at the time, Alonzo Decker, of the Black and Decker fortune, or Talbot County’s John Roberts, who would play a leading role in securing over $10 million from his friend Hank Greenberg’s Starr Foundation. It would be seen in the careful cultivation of Chestertown’s wealthy and eccentric Wilbur Hubbard, developing a relationship with Oxford’s Ted and Jennifer Stanley and Salisbury’s Perdue family.

For the Caters, the search for philanthropy had no limits. Beyond their dogged pursuit of some of America’s wealthiest, they had no hesitation in recruiting some of Chestertown’s devoted gardeners, including Water Street saints Erma and Karl Miller, in working in the Hynson-Ringgold garden once a week. They convinced Henry Kissinger to keynote a fundraising event in Downtown Baltimore for free to benefit Washington College. And it is a matter of record that they badgered Washington high profile personalities such as Lady Bird Johnson, Bill Moyers, Ben Bradlee, George Will, Roger Mudd, Eric Sevareid, Ramsey Clark, Harry McPherson, James Symington, Birch Bayh, Art Buchwald, and beltway comedian Mark Russell to weekend in Kent County to help the college.

The same was true for trustee recruitment. Demanding such people as intellectual Mortimer Adler, Houston Post heir Jessica Catto, Kettering Foundation’s David Matthews, Dartmouth College president David McLaughlin, Lawrenceville School headmaster Si Bunting, Alex Brown Managing Director Jim Price, Baltimore civic leader Walter Sondheim, and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Will Baker.

Nor was this treatment limited to those only having fundraising potential. The Cater address book was the source of the country’s leading intellectual leaders of the time. Friends like writer Toni Morrison, journalist Lou Cannon, poet Wilbur Wright, columnist Meg Greenfield, historian John Hope Franklin, Washington Post editor Phil Geyelin, academic Adam Yarmolinsky, Claremont Graduate University’s John Maguire, and the United Nation’s environmental leader, Maurice Strong all came to Chestertown for some Cater hospitality. And those Cater salons and workshops, including the Aspen Institute Wye Faculty Seminars, made this small college one of the brightest intellectual hubs on the East Coast at the time.

That name-dropping exercise did far more than add a certain panache or pride with students and faculty; it was the Cater calculation that this flow of America’s best and brightest would produce what Washington College needed most – money. And they were right.

That name-dropping exercise did far more than add a certain panache or pride with students and faculty; it was the Cater calculation that this flow of America’s best and brightest would produce what Washington College needed most – money. And they were right.

As the school’s profile rose in the New York Times and Washington Post pages, so did its funding. The Caters found financing for a new Decker science building, the Larrabee arts center, a Chester River pavilion, a new aquatic center, six new dormitories, and the school’s flagship Casey Academic building. They restored the school’s historic William Smith Hall, the O’Neil literary center, and renovated its administrative Bunting Hall. And with the help of notable board members such as Chestertown’s Christian Havemeyer and Turner Construction’s Howard Turner, the campus was physically united with the closing of Gibson Avenue with Mayor Elmer Horsey’s blessing.

The school’s endowment and scholarship funding also saw that growth trend. With only $14 million in principal at the start of the Cater years, an embarrassingly small number for a school over two hundred years old, that number was close to $100 million in the year they retired. Dozens of new scholarship funds opened up, many addressing the need to support minority students to improve the school’s painful lack of diversity significantly.

And finally, the Caters challenged the school’s alumni to step forward with operational support. From having only 25% of the school’s graduates donating in 1982, that number grew to 54% over time. Not only was this one of more satisfying accomplishments for Libby and Douglass, but it also set records. In their last year, the school joined the company of Dartmouth and Princeton in the top five schools with the highest percentage of alumni giving. It was also when WC alumni like the head of Bell Labs William Baker, CEO Bill Johnson of IC Industries, and even Hollywood’s Linda Hamilton came back to the fold to help a school they had long forgotten.

With news of Libby Cater’s passing last week, an essential chapter of Eastern Shore history has come to a close. Like most institutional memory, the Caters years have invariably faded over time. Still, it is hard for those of us who were fortunate to witness this extraordinary act of stewardship not to believe that for one brief shining moment, the stars had aligned for this unique school, and it was finally getting what it had always deserved.

Dave Wheelan served as Vice President of Development and College Relations during the Cater years of 1984-1990. He now is the publisher of the Spy Newspapers.

John Fischer says

Nice piece, Dave. One can feel the admiration and respect.

David Tull says

Nice article

Maureen Curry says

Dave – what a beautifully written article, thank you!

Ross Jones says

Having had the pleasure of knowing both Doug and Libby, I was so pleased to read your words of tribute and admiration for their extraordinary commitment to Washington College and Maryland’s Eastern Shore. A lovely piece.