This is a story about a resilient woman and an equally resilient house.

First, the House. It is known as Bloomfield Manor, located in Centreville, built around 1760, and owned by Mary Edwardine Bourke, who inherited it from her grandfather just before the Civil War. When Bourke married, the house was deeded to her husband, who sold it during a rough financial time. In an attempt to get it back, Bourke, a historian, wrote a detailed account of the Eastern Shore–Queen Anne’s County: Colonial Families and Their Descendants based on interviews with plantation owners, their families, and former slaves. In the book, she also spoke her beloved former home and how she would stand at the window, looking down on the back lawn where her great-grandfather, grandfather, son, his wife, their two children, and three of her own babies were buried. She spoke about her longing to return to this home, which held so much history, pain, and love. Selling the book at 2.50 per copy, Bourke made enough money to regain ownership of her house.

After Bourke’s death, Bloomfield Manor was sold and altered several times, eventually coming under the control of the Queen Anne’s County government becoming part of the County Park called White Marsh. The County tried to find a use for it, but after years of deterioration, they started to talk about tearing it down.’

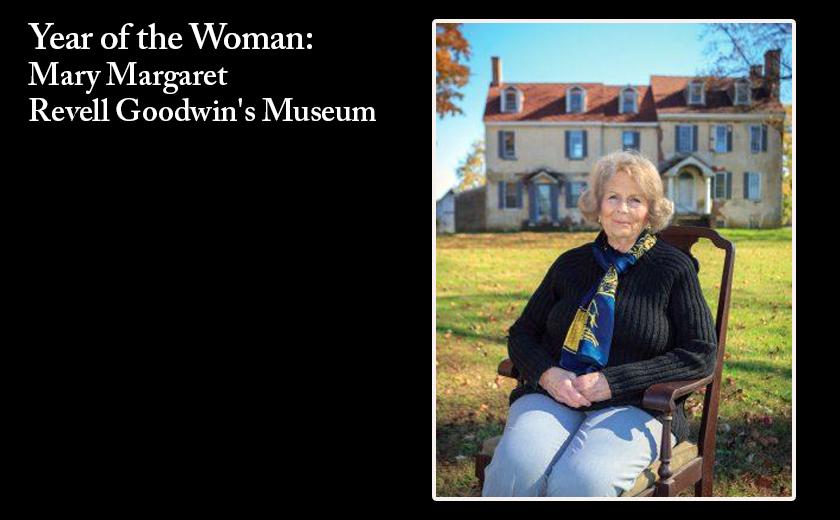

This is the part where the resilient woman comes in. No, not Mary Edwardine Bourke, but like her, a historian with a vision. “I went to the County and said: ‘I’ve wanted to do a woman’s museum for a long time. Let me have a lease.'” And that’s how Mary Margaret Revell Goodwin, Queen Anne’s County historian formed the Mary Edwardine Bourke Emory (MEBE) Foundation and got herself a 25-year lease to develop the Maryland Museum of Women’s History.

But that’s not the entire story. There is the matter of having to raise 3-4 million dollars to renovate the house and meet modern safety standards and codes. And to be honest, there is the matter of not being taken seriously. To prove her point, when the foundation decided to go for a bond bill last year and asked permission from the commissioners, Revell Goodwin was told, “You go do that, Mary Margaret,” and then they forgot all about it. So, for three days, she knocked on doors, visiting all of the women and all potential voters in the legislature, handing out information of what the foundation was and what they were proposing to do. She got her bond bill, much to the amazement of the commissioners.

She also hit red tape when one County Administrator felt they could tell her what they were willing to do with grant money she had secured. It surprised her. As Revell Goodwin explained, “This is not my first rodeo in terms of raising money, but it’s always been for my projects. I have had a few highly successful ones. You can start with me being the first woman to live underwater. And I did the project with the help of the US Navy and Jacques Cousteau, who built all my special equipment. We also beat the Russians by three weeks.”

That comment, casually and unpretentiously stated during our conversation, doesn’t even begin to cover what this extraordinary woman has done in her life. Oh, and did I mention she’s about to turn 83 in August? Not that life has been easy for her. But as she’s proven with her dealings with bureaucracy, she’s not about to let anything stop her.

“It got to the point where this County Administrator was giving me such a bad time,” said Revell Goodwin, ‘that I wrote him an email and said, ‘You were born in 1962, weren’t you? I said that’s the year I set five world records, including swimming the Strait of Gibraltar. You weren’t even out of diapers when I did that. You don’t be talking to me the way you have been.'”

Her reputation as one of the greatest open water long-distance swimmers came about after contracting polio as a child and using swimming as physical therapy. Despite her parent’s objections about becoming an athlete, Revell Goodwin continued for years to secretly pursue her obsession. Once her parents found out, they gave her an ultimatum to quit the sport. They would not speak to her again for a decade.

Revell Goodwin knew she had made the right choice when she began to set records in the United States. However, she wanted more and set her sights on competing in Europe. She raised money to help finance this new dream and again set records, including a double swim of the Straits of Messina, from Sicily to Italy and back, making her the first woman and the first American to do so.

She nostalgically remembers this as her most favorite swim, and it came about with a phone call to the home of the wealthiest Sicilian mobster on the island. He had been showing off his latest project of a special airborne boat for use in the Mediterranean. “I asked him for a plane ticket and room and board in his gorgeous hotel on the shores of the Messina Straits, and he said yes. When I got there, I was sent to the harbor where the Admiral’s ship of the 6th fleet was docked. The Admiral held a staff meeting for all aboard to help me, including his gorgeous Italian Navy assistant, who was assigned to make it all easy for me in Messina. On the day of the swim, I had four US Navy Seals, (first ever assigned outside the US) stationed at a new base in Catania. They brought the small boat to go with me, and they also brought a whole bag of American flags. As each flag on the boat got wet, another one came out of the black bag and was placed on the stern so that with every breath I took, I could see it. There were thousands to greet me when I arrived back in Sicily after crossing to Italy and back.”

After returning to the States, she was recruited for a job at the Pentagon, helping to direct the Navy’s first Environmental and Conservation office. In a picture she shared with us, Revell Goodwin sits at a table with the highest admirals from 57 nations at a 3-day meeting. On her right side is Joseph Grimes, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and on her left is Jacques Cousteau, who she had brought in from Paris to headline the meeting that day.

For 13 years, she turned her attention away from her athletic career, and then her polio returned, and she needed surgery.

Six months after the operation, she began running 10ks, and at the age of 40, retired from the Pentagon to once again pursue competition, but this time in long-distance running. Deciding to focus on the Far East, Revell Goodwin made a phone call to Lee Iacocca, the CEO of Chrysler Corporation, who agreed to sponsor her 2,000-mile run across Japan. Kodak sponsored her run through the Himalayans, again, arranged through a phone call.

Another photo shared by Revell Goodwin shows her with her German Shorthair Pointer, Velia, at the top of one of the most challenging passes in the Himalayas, the Thorong La. “It was the worst place to ever be caught in bad weather,” she said. “We started at 4:30 in the morning for our climb through that pass. The temperature was five below. It took us five and a half hours to climb through that pass. Both of us so tired and in such air that we were very sleepy. We could not, however, stay to rest because it was too dangerous to be caught in any bad weather up there–17,769 was the altitude, one of the highest for any known dog. Velia thought she was in heaven!”

Before settling down in Centreville, she also made BBC documentaries, wrote a children’s book, and raised sea otters. Not surprising, Disney (yes that Disney) recently expressed interested in making a movie based on her life.

So, when Revell Goodwin says she’s committed to raising money for a museum that will give the women of Maryland the recognition they deserve, believe that she will do all within her power to make it happen. “I never had an agent or a representative,” she says. I have had major sponsors, and yet the people I deal with in Queen Anne’s County cannot imagine that what I am now undertaking is possible.”

She is not about to give up without a fight. “I try to have a plan B, along with extra arrows in my quiver. I will be using some of those,” she says. One of the arrows might be a ‘really major’ Maryland corporation who is interested in speaking to her about the museum. “If one or more of those people get on board, this place will go forward.”

For now, she’s envisioning how the rooms will be set up, where the permanent collections will reside, and what to do with the offers of papers and pictures, videos, etc. she’s getting from all over the state. “We would have exhibits specifically about individual women, but we also would be doing research, putting on conferences. This museum would become a cultural women’s resource center as well,” she said.

The original plan had been to open by this August to commemorate the anniversary of the 19th amendment, during the very month it was ratified. However, like for the rest of the world, COVID-19 stopped any ongoing progress in the house. But that’s not going to prevent the celebration from going forward.

“The exhibit is called You Are the Vote,” she said “we’re doing what will be the major 19th amendment history. Even though we can’t open to the public, we’re going to live stream it on the internet.”

Revell Goodwin looks forward to highlighting a couple of trailblazing women in the future. One is Hannah Till, George Washington’s personal cook. Her story will be told as a ‘live’ scene of how she would have been set up in a tent with cooking utensils in the middle of the harshest snowstorms, after giving birth to her first son.

Then there is Barbara Hillary, a nurse from New York who was the first black woman to reach the North Pole at the age of 75 and the South Pole at the age of 79.

Says Revell Goodwin: “I want each little black and brown and white girl to have people that they can relate to, who did neat things and know that they can do those things too. It just takes that kind of work and dedication to get it done.”

That same work and dedication is the reason that the story of Mary Margaret Revell Goodwin deserves to be part of the museum’s exhibit, not only for the life she led but for the question that she keeps asking: “Who will tell these women’s stories?”

She hopes that the answer is the Maryland Museum of Women’s History.

Val Cavalheri is a recent transplant to the Eastern Shore, having lived in Northern Virginia for the past 20 years. She’s been a writer, editor and professional photographer for various publications, including the Washington Post.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.