American Thanksgiving is a tradition that began with the Pilgrims in 1621. They celebrated a three-day harvest festival with the local Wampanoag tribe. George Washington and the Continental Congress declared the first Thanksgiving Day to be in November 1789: “A day of public thanksgiving and prayer” for the successful end of the War for Independence. A national Thanksgivings Day was proclaimed by President Lincoln on October 3, 1863.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln, in an effort to bring Americans together, issued Proclamation 106 (October 3,1863) establishing a National day of Thanksgiving: “I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States…to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise…to heal the wounds of the nation to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union…” To help spread the word, America’s popular magazine Harper’s Weekly published a copy of the proclamation on October 17,1863.

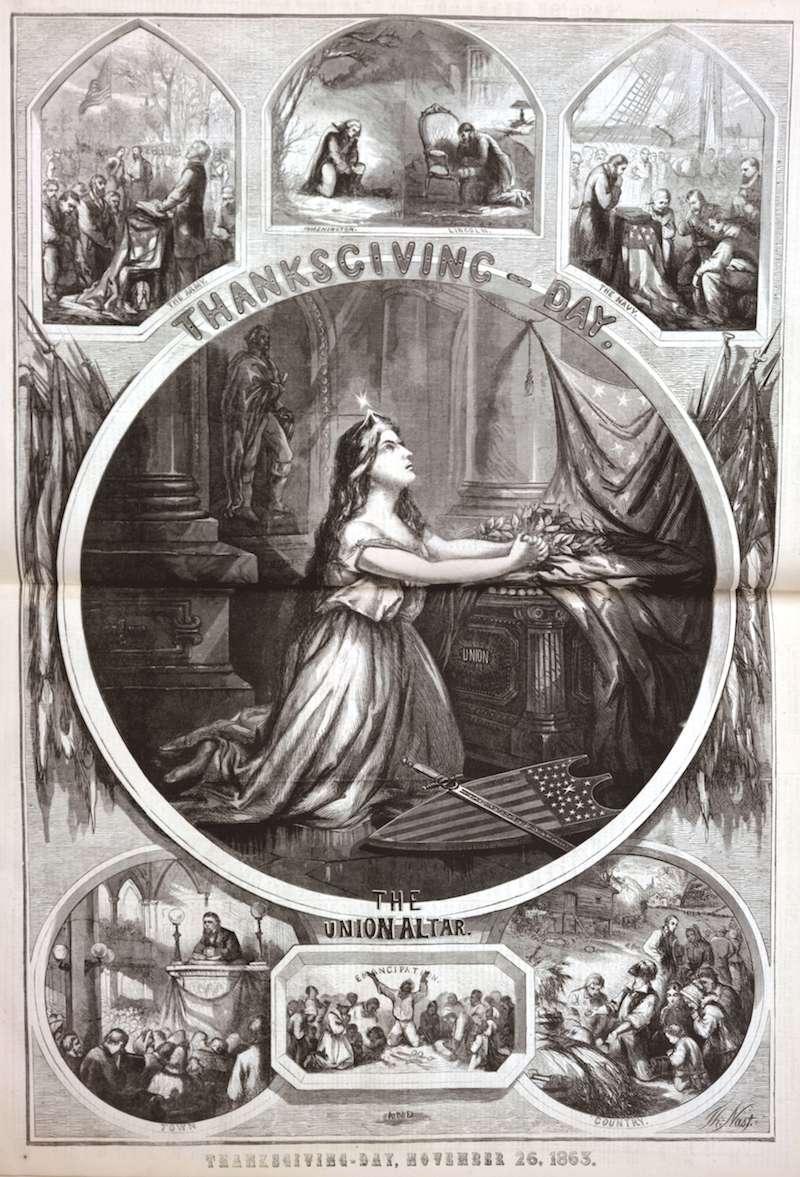

Thomas Nast’s cartoon “Abraham Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation” (1863) was published as a two-page spread on December 5,1863, by Harper’s Weekly. In the center circle, a female figure representing Columbia kneels at The Union Altar. Her shield and sword rest on the floor in front of her. The altar is draped with the stars of the American flag, and a laurel wreath of victory sits upon the altar. A single star, for unity, shines from Columbia’s tiara. In a niche behind her is a sculpture of George Washington. Tattered American flags are grouped together on either side of the circle. Above the circle in large letters is the proclamation Thanksgiving – Day.

Above the circle, from left to right, soldiers, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, and sailors kneel in prayer. Across the bottom of the cartoon, townspeople kneel in a church, a group of African Americans celebrate Emancipation, and people from the country kneel giving thanks for a good harvest.

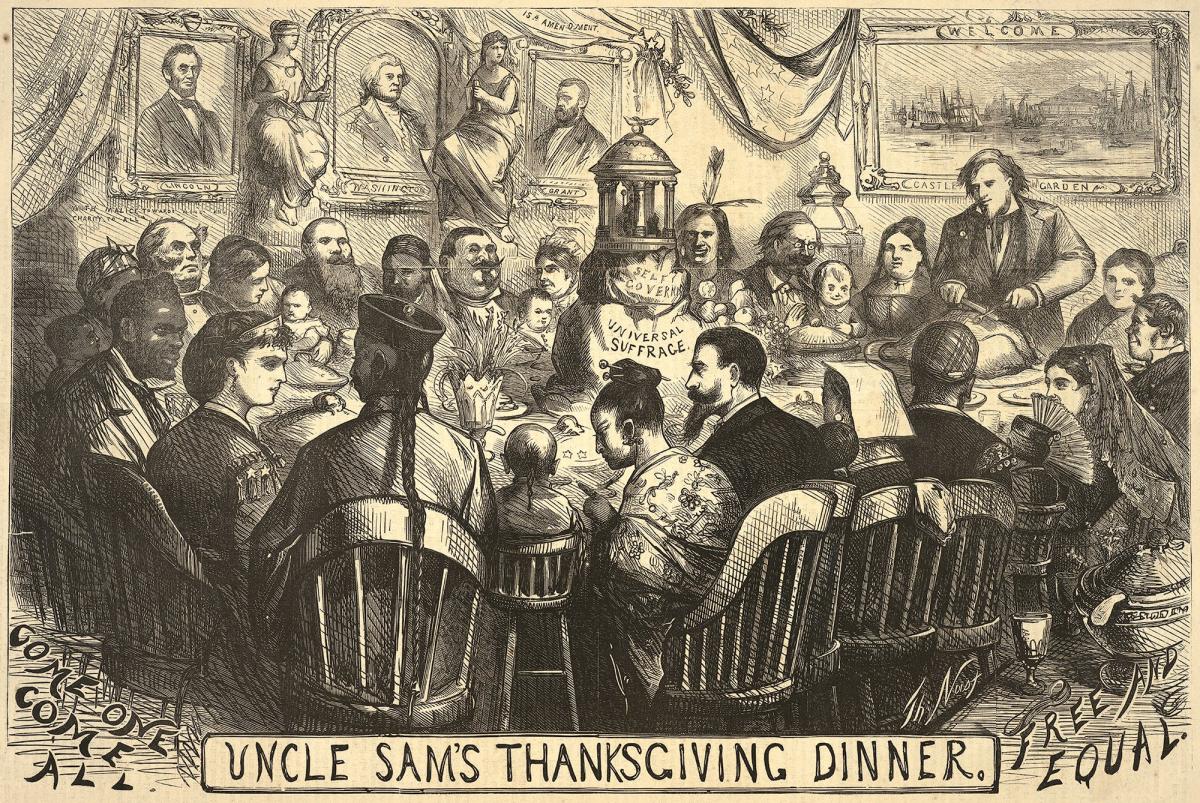

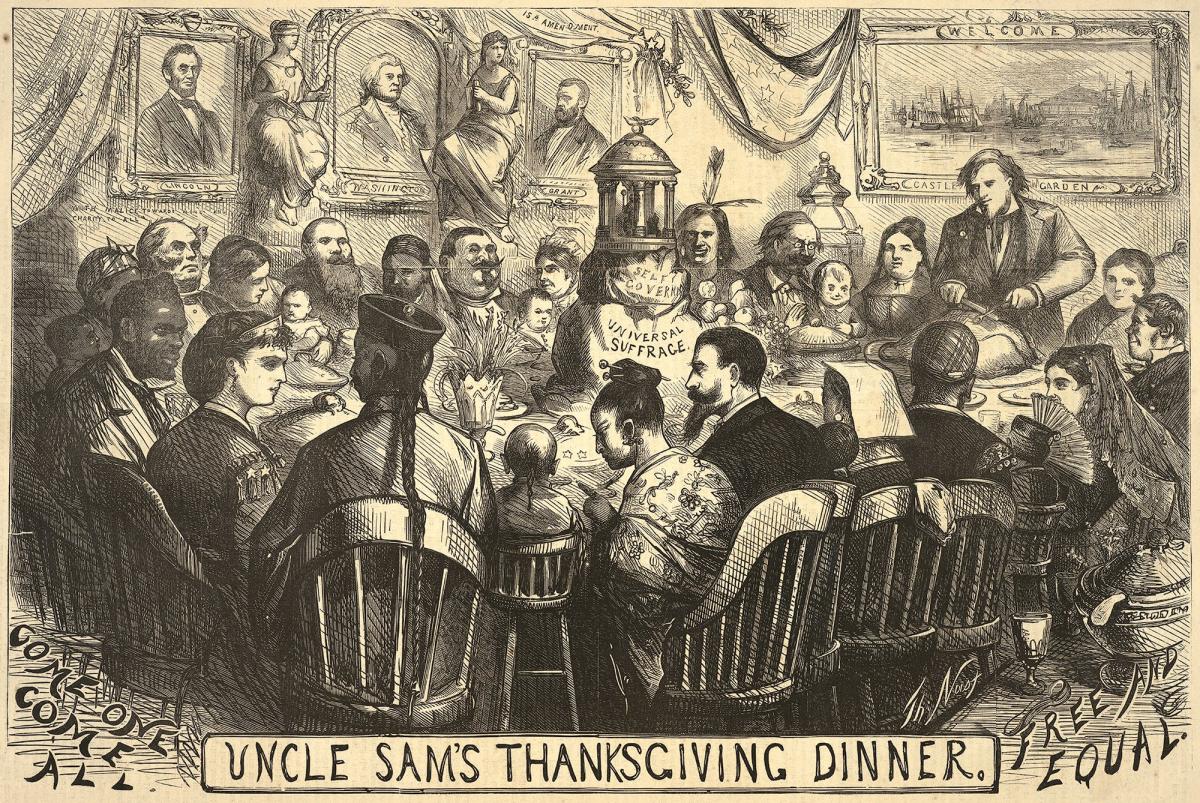

Thomas Nast’s cartoon “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” was published on November 20, 1869, in Harper’s Weekly. On either side of the title “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” the words “Come One, Come All” and “Free and Equal” let the viewer know that this is a dinner where all are welcome.

At the head of the table, Uncle Sam carves the Thanksgiving turkey. On the wall behind him is a painting of Castle Garden, where immigrants were processed in New York before Ellis Island. As one might find at a museum, plagues attached to the top and bottom of the frame are engraved with the words Welcome and Castle Garden. Columbia sits across the table from Uncle Sam; she wears a tiara and what appear to be medals on her dress sleeve. The centerpiece on the table is tiered. The words Universal Suffrage are carved into the large rock at the bottom. A smaller rock is carved with words Self Government. At the top is a small circular temple, its roof is decorated with stars and an eagle perches atop a globe.

Nast places portraits of Lincoln, Washington, and Grant on the wall behind the table. Sculptures between the portraits represent Liberty and Justice. On the wall below Lincoln’s portrait is the statement “With malice toward none and charity to all.” Above Grant’s portrait is a banner labeled 15th Amendment. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified on February 3, 1870, states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Nast presents an amalgam of American society seated at the table. In conversation with Columbia are a man from China, seated at her right, and an African-American at her left. Both are present with their wives and children. To the right of the centerpiece is an American Indian wearing a feathered headdress. Among the others enjoying the dinner are German, Arab, Irish, and Spanish immigrants. Nast represents the families with humanity and dignity. He was a proponent of democracy and national unity, and he hoped to see America fulfill its promise.

A note about the cartoons: These two pieces were not cartoons in the usual sense. Cartoons originally were working drawings for artists as preparation for a finished work. Thomas Nast was famous for his cartoons that lampooned American political persons and events. However, these two works, along with many others that were published in Harper’s Weekly, depict subjects that were important to Nast. They carried serious and significant messages concerning Nast’s belief in the promise of American democracy.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING TO ALL

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.