There’s a powerful sense of place and history in the stories that weave through the Artists Fellowship exhibit on view at Emmanuel Church Parish Hall through April 1. Allen Johnson’s colorful oil paintings of Black watermen oystering on the Chester, the very river that brought their enslaved ancestors, set the scene, while history unfolds in Mike Pugh’s stunning retelling of the nearly forgotten story of a white Quaker abolitionist wrenched from his home, an 18th-century house where Pugh himself now lives, to be tarred and feathered by an angry mob. In another remarkable coincidence of location, Jason Patterson created a portrait of a man enslaved at the Spring Street building that is currently being renovated to be the home of the Kent Cultural Alliance. Set in Kent County’s familiar landscapes, these artworks tell stories that literally bring home the anguish and heartbreak wrought by slavery and the lingering consequences of racism.

Cosponsored by the Kent Cultural Alliance and Washington College’s Chesapeake Heartland project, what might seem a small, unassuming show of work by five local artists (all African Americans except Pugh) in a church parish hall, turns out to be startlingly moving and profound. Quiet and rural as it may be, Kent County is revealed as a microcosm of the African-American story and these artists are here to tell it.

You can read about Chesapeake Heartland online or in the brochure provided at the show, but suffice to say that it grew from the recognition of Kent County as the locus of four centuries of African American history and culture from the earliest days of slavery through the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement and on to the painting of the Black Lives Matter mural on High Street. Drawing on materials from the CH Digital Archive and the personal experiences of its artists, this show personifies what art really is for—the searching out, understanding and communication of the heart-deep stories that are the reality behind our everyday lives.

Two major themes run throughout the show—the painful persistence of racism and the limited options for employment for African Americans in Kent County. Each of Johnson’s paintings uses specific details and the engaging candor of his folk art style to tell the stories of the everyday lives of his watermen and oyster shuckers, while Gordon Wallace’s series of paired photographs document factory employment in Chestertown.

A trio of photos Wallace discovered in the CH Digital Archive were taken at Vita Foods, once the town’s largest employer. Paired with each is one of his own photos of the present-day site presented in a similar snapshot style. Again the threads are interwoven. His own grandmother appears in a group of women in Vita Food uniforms and caught in a similar position as a worker unloading products at Vita Foods, his cousin performs a task in his job at Dixon Valve, which took over the location from Vita Foods and after recently moving to its new home on the edge of town, donated the site to Washington College.

Yumi Hogan, Allen Johnson and Ruby Johnson with Johnson’s paintings at the exhibit’s opening reception

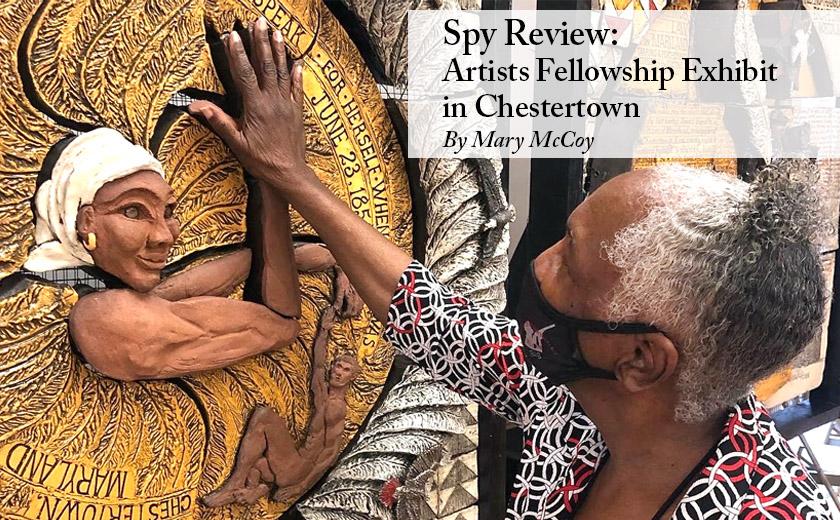

The sense of place that Johnson and Wallace evoke expands in Pugh’s two-panel sculptural ceramic relief. With a drawing of James Lamb Bowers’s home, now Pugh’s, in one corner, the righthand panel is incised with an account by Bowers detailing the terrifying night in 1858 when he was attacked. It includes a list of his attackers, whose surnames are still familiar in this area. On the other panel, the head and muscular arms of a Black woman brimming with indomitable spirit burst out from a disk of feathers ringed with lettering that tells her story. She is Harriet Tillison, a free Black woman, who was also tarred and feathered on the same night before disappearing from history. Powerful in its modelling and jampacked with evocative symbolism, this artwork was conceived by Pugh to ultimately become a public mural somewhere in Chestertown.

That the violence of racist behavior is still with us takes gut-wrenching form in Bogey Brown’s series of altered photographs. Beginning with a few notes scrawled on what is essentially a documentary photo of a young African American man holding a sign telling the story of Anton Black, killed by police in Greensboro in 2018, the series moves in four successive steps to a ghost image of the protester virtually swallowed by a head-spinning swirl of clashing colors. In the wordplay of its title, “Losslostlose,” and in the progression of images from documentary to almost hallucinatory, the artist tells another story—how the whirlwind of emotional confusion caused by this tragedy and too many similar incidents causes profound wounds to the psyche.

This exhibit speaks of the knotty truth that too little has changed in the more than a century and a half between the two incidents, but it also offers healing, through supporting these artists in their exploration of African American history in Kent County and making their works available to the community, as well as in giving the subject matter the prominence and dignity it deserves.

It’s particularly in Patterson’s portraits that the strength and humanity of local African Americans comes to the fore. Like Wallace, he turned to the CH Digital Archive for source material, searching out photos of Black members of this community. Working from these, he created nuanced portraits in soft pastel on raw canvas mounted on linen. Finished with a gel glaze that gives them depth, elegance and an aura of significance, these sensitive portraits are further enhanced by substantial, well-crafted wooden frames, endowing them with a memorable, monumental presence.

Chesapeake Heartland and Kent Cultural Alliance are to be applauded for conceiving of the Artists Fellowships that supported these artists in their work, making this exhibit, with its interwoven tapestry of stories, possible. Artists are the first to work for positive change in any community, and here they have unfolded a host of potent truths rooted firmly in our very own landscape and community and ready for our consideration.

CUTLINES:

Yumi Hogan, Allen Johnson and Ruby Johnson with Johnson’s paintings at the exhibit’s opening reception

Chesapeake Heartland Community Historian Carolyn Brooks touches Mike Pugh’s mural

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.