U.S. senators from Maryland and Pennsylvania are raising concerns over the nitrogen levels in the Susquehanna River, which in turn threatens the health of the Chesapeake Bay. They are calling on the U.S. Department of Agriculture to increase aid to watershed states.

In a letter sent last week to U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, Maryland Senator Ben Cardin and Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey Jr., both Democrats, suggested inadequate federal resources are causing shortfalls in Pennsylvania’s nitrogen reduction through the federally mandated Watershed Implementation Plan (WIP).

“The USDA must live up to the leadership role it’s been given in our region by providing improved financial and technical resources necessary for the Susquehanna River Basin and Chesapeake Bay Watershed farmers to meet the goals of the state WIPs,” said the letter.

Through quoting the 2009 Chesapeake Bay Executive Order, Cardin and Casey outlined the secretary’s duty to concentrate federal programs within priority areas located in Chesapeake Bay counties.

“We expect USDA to fulfill its legal duty to provide greater resources to farmers in the Susquehanna River Basin and Chesapeake Bay Watershed,” they stated.

Nitrogen Reduction Falling Short

The senators’ unease arose from the 2014 Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint, which calls for greater nitrogen reductions.

While Pennsylvania has met some goals, on-track to reduce phosphorous and sediment pollution by 60% in 2017, nitrogen levels remain a problem.

“Pennsylvania has made progress in the agriculture and wastewater sectors to ensure implementation is occurring, even though all its milestone commitments were not achieved,” said the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in its February 2015 assessment. “However, projected reductions for nitrogen would be substantially behind schedule.”

Farmers’ Efforts Unrecognized?

The Pennsylvania Farm Bureau, representing 60,000 farms and rural families across the state, believes the EPA’s computer calculations misrepresent pollution reduction efforts along the Susquehanna.

The EPA measured only federal cost-share programs going into effect, also known as Best Management Practices (BMP).

But BMP programs like riparian buffers, vegetated buffers, contour strips and no-till farming are in many cases fully paid for and implemented by farmers themselves, therefore not measured in the report, according to the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau.

“One of the top frustrations among Pennsylvania farmers located in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed has been the lack of credit they receive for all of the efforts they’ve taken to reduce runoff and soil erosion,” said Mark O’Neill, director of media and strategic communications.

The farm bureau would welcome additional federal funding for technical assistance, in order to help the farmers paying for BMP programs, he said.

Pollutants in the Susquehanna

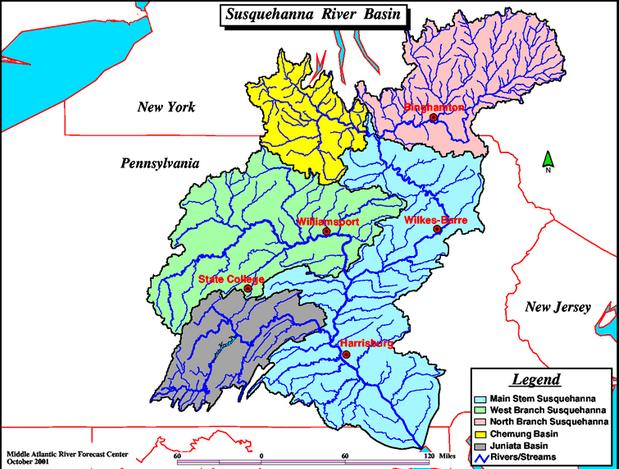

The Susquehanna River stretches 464 miles through Pennsylvania, New York and Maryland, picking up nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment along its way. It provides half of the freshwater flowing into the Chesapeake Bay,

As of 2009, the EPA estimated Pennsylvania to be the source of nearly half the nitrogen running into the bay (44%). The Susquehanna was estimated to be carrying 46% of all nitrogen entering the bay.

Earlier this month the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service confirmed a cancerous tumor found on the lip of a small-mouth bass caught on the river last year.

The PFCB press release indicated finding cancerous tumors in fish is extremely rare.

Groups like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) and PFCB believe this case will draw attention to their concern over the health of the lower 98 miles of the river, claiming it is “compromised,” and needs a restoration plan.

According to the Bay Foundation, about 19,000 miles of Pennsylvania’s rivers and streams are impaired.

“As we continue to study the river, we find young-of-year and now adult bass with sores, lesions and more recently a cancerous tumor,” said Pa. Fish and Boat Commission Executive Director John Arway. “We’ve known the river has been sick since 2005, when we first started seeing lesions on the smallmouth. Now we have more evidence to further the case for impairment.”

While agriculture is not the only contributing factor for an unhealthy bay, it is a large contributor.

“Sediment and nutrient runoff from farm fields and suburban and urban lawns and hard surfaces are two of three leading sources of stream impairment,” said CBF Pennsylvania Executive Director Harry Campbell.

2017 Programs to Meet 2025 Standards

The Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), was created in 2010 to put the bay on a “pollution diet.” The plan requires states contributing to the watershed reduce their overall nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment pollution output.

To meet its overall TMDL allocations, Pennsylvania has committed to achieving approximately 75% of its necessary nutrient and sediment reductions from the agricultural sector.

“We are committed to helping our farmers and committed to helping reduce the amount of pollution that reaches the Susquehanna River Basin and Chesapeake Bay Watershed,” said Cardin, who is a senior member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. “We can do both effectively, with the right resources.”

TMDL programs are required to be in place by 2017, in order to have reduced overall pollution by 60% in 2025.

By Rebecca Lessner

..

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.