The Feast of Stephen occurs each year on December 26. The feast day may be familiar; it is mentioned in the carol “Good King Wenceslas” (1853). There was in fact a St Stephen and a good King Wenceslas. Boxing Day also is on December 26.

“St Stephen Martyrdom” (1324)

St Stephen (c. 5-36 CE) was one of the seven deacons of the early Christian church in Jerusalem. He was known for caring for poor, often forgotten people by giving them gifts of food and other necessities. He was a Hellenistic Jew, and he preached about the synagogues’ slight of Hellenistic Jews and favor toward Hebrew Jews. The Sanhedrin, the supreme legislative and judicial council in ancient Israel, accused Stephen of blasphemy against Moses and God. “St Stephen Martyrdom” (1324) (10’’x20’’), by Bernardo Daddi (c.1290-1348) of Florence, is one of eight panels from an altarpiece in the church of Santa Croce. On the left side of the panel is a depiction of the trial before the Sanhedrin. St Stephen prays as he is found guilty. On the right side is a depiction of his stoning. He is acknowledged as the first Christian martyr.

Bernardo Daddi was a follower of Giotto who introduced greater realism in his painting. The human figures have more natural proportions, gestures, and expressions. His use of shadow gives them weight and mass. Fabrics drape naturally around their bodies. Their feet appear to be flat on the ground. Although faces are similar, he attempted to represent distinct individuals. His settings begin to have perspective. He attempted to paint a usable space. Although the leader of the Sanhedrin is too tall to stand up in the room, the door to the outside is tall enough to accommodate St Stephen and the others. Outside, a green lawn and a deep blue sky replace traditional solid gold as a background.

“The Martyrdom of St Stephen” (1671)

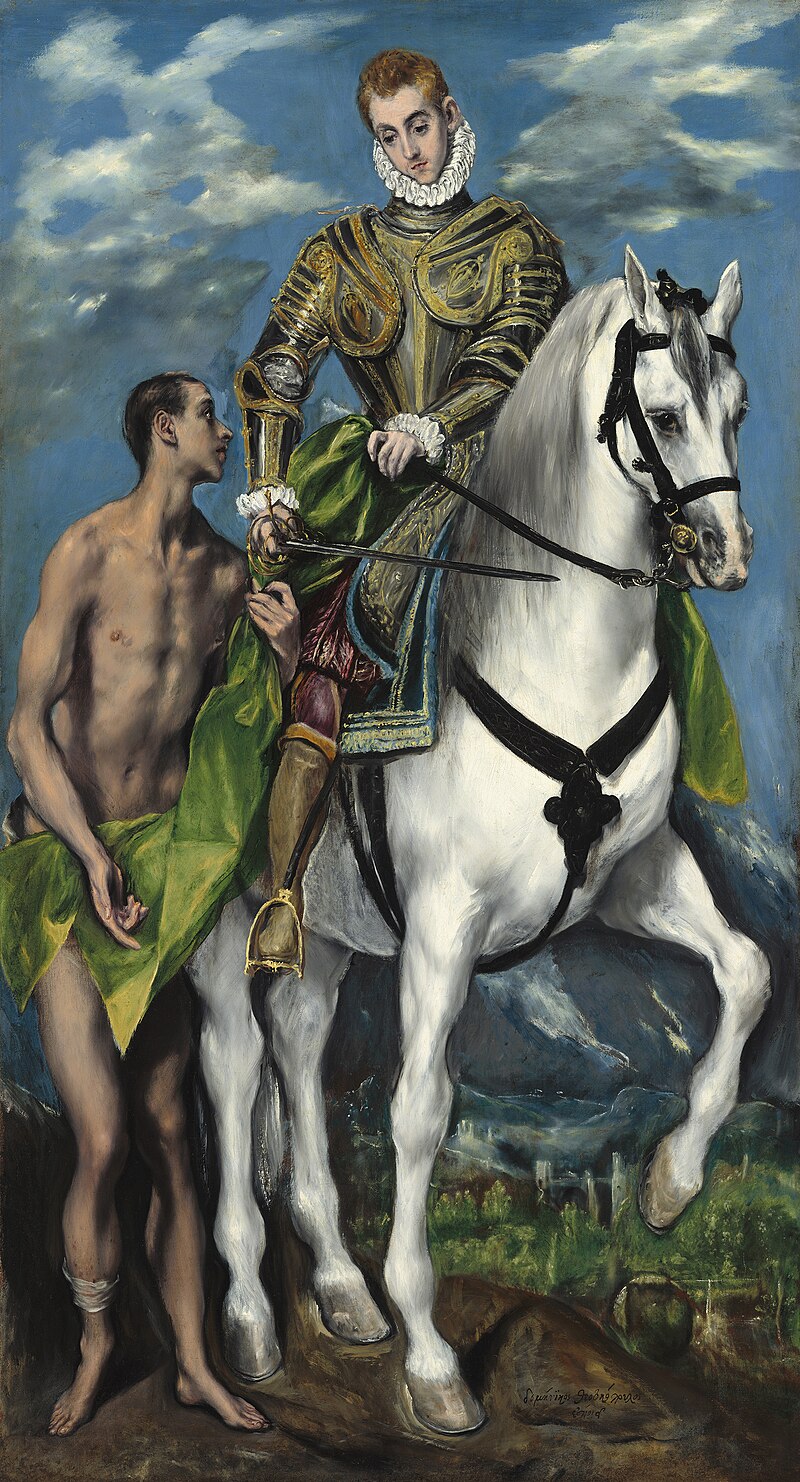

“The Martyrdom of St Stephen” (1671) (172”x109’’), by Flemish Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), offers a striking comparison between the early attempts at realism in the Early Renaissance in Italy and the full-blown realism of the 17th Century. On the left panel, Stephen preaches to the people about his concerns. He stands on the steps of a classical Roman building. Three of those around him listen intently. Perhaps the elderly figure in white with the elegant blue and gold on his robe is a member of the opposition. He listens intently, but with a hand held behind his back.

The stoning of Stephen is depicted on the central panel. Well-muscled men throw the stones with power. Stephen has begun to turn the ashen color of death. He looks up and cries out, “Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God.” (Acts 7:54-60) Before he died Stephen forgave his persecutors. In the right corner is Saul of Tarsus, keeping the discarded robes of those stoning Stephen. This act shows his consent to the stoning. Saul would become a major persecutor of Christians until his miraculous conversion on the road to Damascus. He was known from that time as St Paul the Apostle. The right panel is a depiction of the burial of St Stephen.

“St Stephen” (1330-35)

St Stephen was depicted as a young man wearing a deacon’s dalmatic robe. “St Stephen” (1330-35) (33”x22’’) is an early image by the famous Florentine artist Giotto (c.1267-1337). Giotto tried to give Stephen a compassionate expression because he was known to be compassionate. His dalmatic is decorated with elaborately woven bands of gold embroidery. He holds a book as tribute to his faith and his teaching. Giotto attempted to depict realistically Stephen’s fingers holding the book.

The two rocks on his head are symbols of his martyrdom, one of the things all artists had trouble integrating into their paintings. Stephen is the patron saint of deacons, bricklayers, and stonemasons.

In portraits of this period, the golden background was influenced by Byzantine painting. Gold ingots were pounded into thin leaves and applied onto a layer of bole, wet red clay. It could then be incised into elaborate patterns as seen in this work.

“St Stephen” (1476)

“St Stephen” (1476) (24’’x16”), painted by Carlo Crevelli (1435-1495), was commissioned by the Dominicans in Ascoli Piceno, Marche, Italy. They believed Stephen provided an excellent example of teaching and preaching to non-believers. Cervelli was trained in Venice, painted in the elaborate and highly decorative style of Venice, and was known for his extensive use of gold. The dalmatic decorations are an example of the richness of Venetian gold embroidery. The gold would gleam in the candle light of church services. Stephen holds a palm branch, a symbol of martyrdom, also of triumph, peace, and eternal life. Waving palm branches were part of the celebration of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The stones on his head and shoulders are necessary to identify Stephen.

“Wenceslaus fleeing from his brother” (c. 1006)

Wenceslas (907-935) (Vaclav the Good) was not a king, but he was the beloved Duke of Bohemia. He was raised as a Catholic by his grandmother Ludmilla. He was known for his concern and care for widows, orphans, and even prisoners. He spread the Christian faith throughout his kingdom, much to the displeasure of his mother and brother Boleslaus the Cruel. “Wenceslaus fleeing from his brother” (1006) is an illuminated manuscript from the Gumpold Codex, commissioned in 980 CE by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II and his wife. It is a depiction of the murder of Wenceslaus on September 28, 905 by his brother and others on his way to pray in the chapel. The final blow was delivered by his brother. In the illustration, Wenceslaus tries to escape into the chapel, but the priest closes the door. September 28 was declared his feast day and is celebrated in the Czech Republic, Bohemia, and Slovakia. Wenceslas was declared a saint by the people of Bohemia immediately after his death, and the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, declared him be a king.

“St Wenceslas Chapel” (14th Century)

The St Wenceslas Chapel was built in the 14th Century by King Charles IV, and it is the main chapel in the Cathedral of St Vitus in Prague. His tomb and relics are decorated lavishly. Over 1,300 Bohemian gemstones set in gold decorate the lower wall. The 275 square yards of Gothic frescoes on the upper wall depict scenes of his life and the life of Christ.

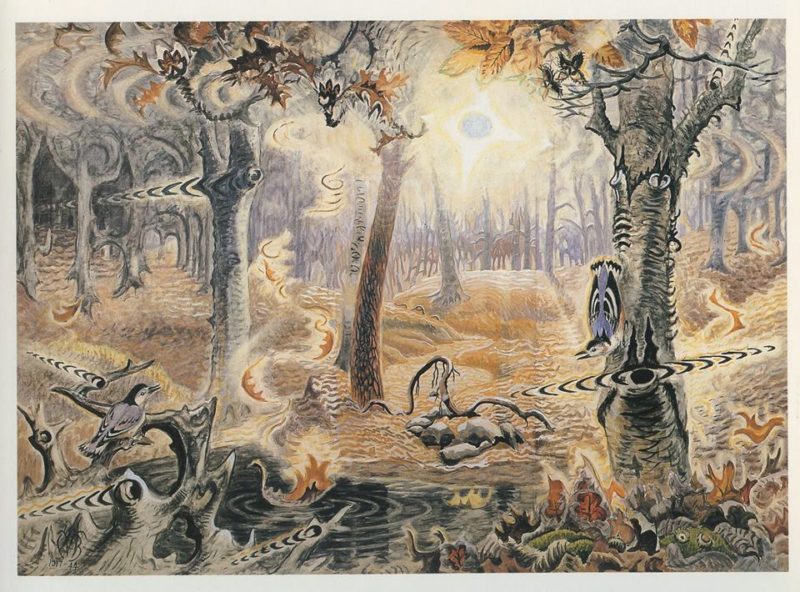

“Good King Wenceslas” (1879)

John Mason Neale (1818-1866), an English Anglican priest, scholar, and hymn writer wrote the carol “Good King Wenceslas” in 1853. His scholarship included an interest in medieval literature and music. He wrote the lyrics to fit the music of the 13th Century Spring carol “The Blooming Time is Here” that he and his partner Thomas Helmore found in a Finnish song book from 1582. The carol was published first in a children’s book in 1849 and then in his “Carols for Christmastide” in 1853.

“Good King Wenceslas” (1879) is an engraving by the Brothers Dalziel. Their engraving company, founded in London in 1839, worked with such artists as Whistler, Rossetti, and Lewis Carol. The engraving was included in a hymn book published by Henry Ramsden in 1879. King Wenceslas and his page are shown trudging through the snow carrying food and aid to the poor people of Bohemia. In verse four, the page, about to collapse, says:

‘Sire, the night is darker now

And the wind blows stronger;

Fails my heart, I know not how,

I can go no longer.’

Wenceslas responds:

‘Mark my footsteps, good my page,

Tread thou in them boldly:

Thou shalt find the winter’s rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly.’

Boxing Day, generally considered an English holiday, is also celebrated on December 26. In Victorian Britain the wealthy gave their servants the day after Christmas off to visit their families. After all they had worked hard preparing and serving the Christmas dinner. When they left, they were given a Christmas box which held food, small gifts, and money. Churches put boxes out for parishioners to leave donations for the poor. The connection between St Stephen and Boxing Day encouraged people to give gifts to those in need, as St Stephen had done.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.