It’s an emotional experience—The Changing Chesapeake exhibit now at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM). It’s unlike anything you’ve ever experienced or anything CBMM has ever done. The Spy was invited to the opening night of the yearlong show at the Steamboat Building gallery. It would also the first time the 70 artists participating in the exhibit would see their work on display. To some, particularly those who don’t usually think of themselves as artists, sharing their work with the world was overwhelming, and more than once, we noticed emotional reactions.

Such it was with Laura Guertin, who wiped away a tear as she found her quilted art “Looking Out at the Ghosts of the Coast” at the gallery entrance. Guertin, whose work portrays dying trees through a window frame, has a Ph.D. in marine geology and geophysics and is a college professor. She started quilting a few years ago as a way to tell ‘science stories.’ “People get drawn to it because no one feels threatened by a blanket, right? And once they see it, I can hook them with the science. This is a serious theme, and we need more action and activity, but we have to bring people to that conversation.”

Lee Hoover was also affected by seeing her photograph, “Pintail,” on the wall. “You prepare yourself, knowing you’ll see your stuff, but then ‘boom,’ there it is.” Her photo is of a name being lettered on a ship stern. “The old ways are disappearing,” she says. “Who paints letters by hand anymore? It’s all done by computer. I’m hoping that people will remember the old ways of doing things. But I also hope they think about how the Chesapeake is in trouble.”

This is a different type of show for CBMM, explains Jen Dolde, Curator and Folklife Center Manager. “We’re usually featuring the work of one person, or we’re putting together a historical exhibit on a specific topic. But one of the things we’re called to do, now that we’re a Folklife Center under the Maryland State Arts Council, is to look not only for the historical voices but also the contemporary ones. These are the voices of all the people and how they live their lives and form their identities. I see this exhibit as a form of documentation.”

To Jill Ferris, Senior Director of Engagement, Learning, and Interpretation, whose focus is on the community, her goal is open up those channels of conversation. “I’m hoping to get some artists to do workshops or talks. There were a lot of submissions about ghost forests, which seemed to be a huge inspiration point, and I’d like to bring them together to talk about that shared image.”

The idea for The Changing Chesapeake started a couple of years ago, with an invitation in 2022 to anyone interested in expressing how climate and cultural change have shaped the Chesapeake. CBMM received over 140 submissions which went through a blind ranking process with community panelists who were unaware if the work they were judging was by someone with a reputation as an artist. Seventy-eight pieces by 70 artists were chosen and included traditional media such as photography, sculptures, and painting, as well as fiber art, stop-motion animation, found-object art, original songs, embroidery, poetry, etc. There was even a novel translated from Italian.

Unlike other museum exhibits where a little label titling the work and identifying the artist is discreetly affixed on the wall, here, to fully understand what you are observing, you are encouraged to take the time to read the artist’s description. Not doing so may cause you to miss some significant and interesting facts about the person, the area, or the historical implication of the piece. In fact, the narrative is an integral part of the exhibit

There is Joi Lowe’s sea glass, shell, and driftwood mobile named after the ship, “The Generous Jenny.” On its own, it’s a beautiful piece, but the meaning behind it is heartbreaking. The artist created it to honor the memory of the unnamed enslaved people who arrived at the Sotterley Plantation in 1720. Each of the 260 pieces that make up the sculpture is a life either lost or determined to survive. For instance, the brown sea glass represents the 91 enslaved men; 20 unaccounted souls are shown as white sea glass, and shells symbolize the 29 people thrown overboard due to a smallpox infection.

The various displays are spread out over two floors, and you’ll soon discover there are themes. “What our Exhibition Designer, Jim Koerner, did,” said Dolde, “was to group the pieces so that they connect, play off the other, and send different messages.” For the community, the fun part becomes going through the rooms and figuring out the association.

For instance, look for the homage to the Eastern Shore’s most iconic symbol, the osprey. Along with the more traditional painting, you’ll find an intricate textile piece that was woven and hand painted. And then there is “Ospreys Don’t Wear Coats,” which shows a whimsical bird dressed for the cool temperature and holding two coffee cup containers. ‘Nests can’t be made with coffee cups’ is stated on the accompanying description by Nicholas Thrift. Thrift, who considers himself a part-time artist, says he was inspired to paint the osprey to express the ‘duality of man and animal, in the midst of environmental catastrophe, through the lens of the humorously grotesque.’ “I wanted him to have a veil of ambiguity,” he said. “There’s hope and fear in the picture, just mashing together.”

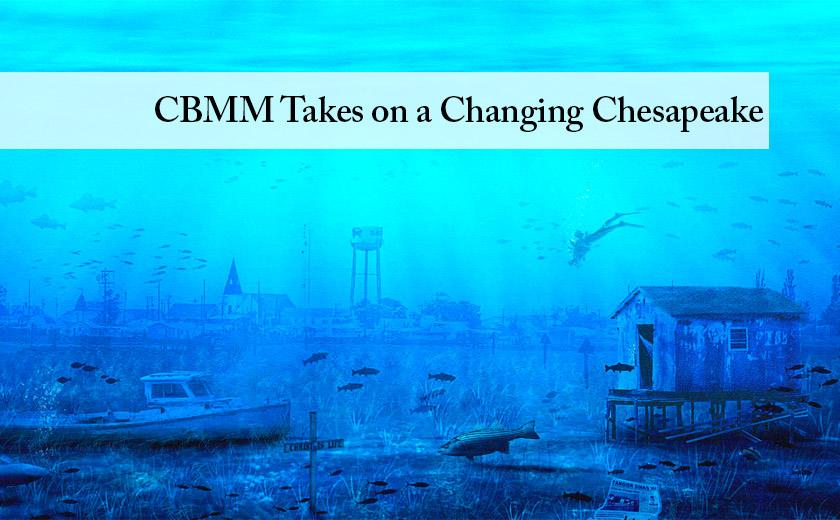

That message of hope and fear is everywhere and in every piece of art throughout the gallery. It’s in Sharon Malley’s oil painting “Momfords Poynt from Space,” which imagines John Smith’s map of the Chesapeake from space. It’s in Thelma Jarvis Peterson’s Celtic-inspired song, “Ghost Forests,” and in the music video “Can’t Work the River” by Peter Panyon and Big Tribe. It’s also found in Nic Galloro’s “Foamberg Fish,” a sculpture made of recycled wood, CDs, aluminum foil, milk cartons, and glass. It’s there when standing in front of “Sea Rise,” a sculpture by George Lorio that explores the relationship between rising sea levels and an affected home, or in the heartbreaking photo montage by Tom Payne of Tangier Island underwater, “Tangier Abandoned.”

“I think that art is uniquely able to capture that poignancy of the human experience,” said Lode. “You can’t always put it in words or name it, but we feel it, and it’s different for everyone. So what one person will respond to in this exhibition will differ from the next person.”

It is that experience that the museum hopes to convey to the public. Pete Lesher, Chief Curator at CBMM, said. “One of the bigger messages that we hope people carry away about the Chesapeake is that we want them to not only love the place and be good stewards of it but also better understand the culture and be better stewards of the culture.”

Dolde agrees. “The Chesapeake is part of our identity. So whether you’re from here, whether you’ve come here and fell in love with it, whether you’ve chosen to move here, or choose to vacation here–there’s something about this body of water. And there’s something about how you experience it. Whether it’s time with family, enjoying the beauty of nature, or admiring the resilience of the traditional waterman in the traditional culture, it’s all just inspiring.”

No matter your connection to the water, you will find something at Changing Chesapeake that will amuse, inspire, or touch you. It will also make you think. And coming once will not be enough.

The Changing Chesapeake is funded through CBMM’s Regional Folklife Center under the Maryland Traditions program of the Maryland State Arts Council. Viewing this exhibition is included with general CBMM admission and free for CBMM members. Visit cbmm.org to learn more.

Frank Carollo says

Wonderful article about an enthralling exhibit. Thanks for helping to spread awareness of this presentation… and thanks to all the artists who made it possible.