A certain glow of righteous beauty surrounds the intense efforts to restore the oyster stocks of Chesapeake Bay.

These humble and magnificent filter feeders make our waters more clear and healthy.

Their living reefs provide vibrant and productive habitat for themselves as well as for multitudes of shellfish, finfish and other species.

Their succulent protein tantalizes our taste buds, nourishes our bodies and sparks optimism for a future of living harmoniously with nature.

Within that blooming cornucopia emerges the unique and rippling economic and cultural opportunity manifested in associated jobs and regional lifestyle.

It’s that rich vein of opportunity that Ferry Cove Shellfish, on the shores of the Chesapeake just north of Tilghman Island, plans to mine.

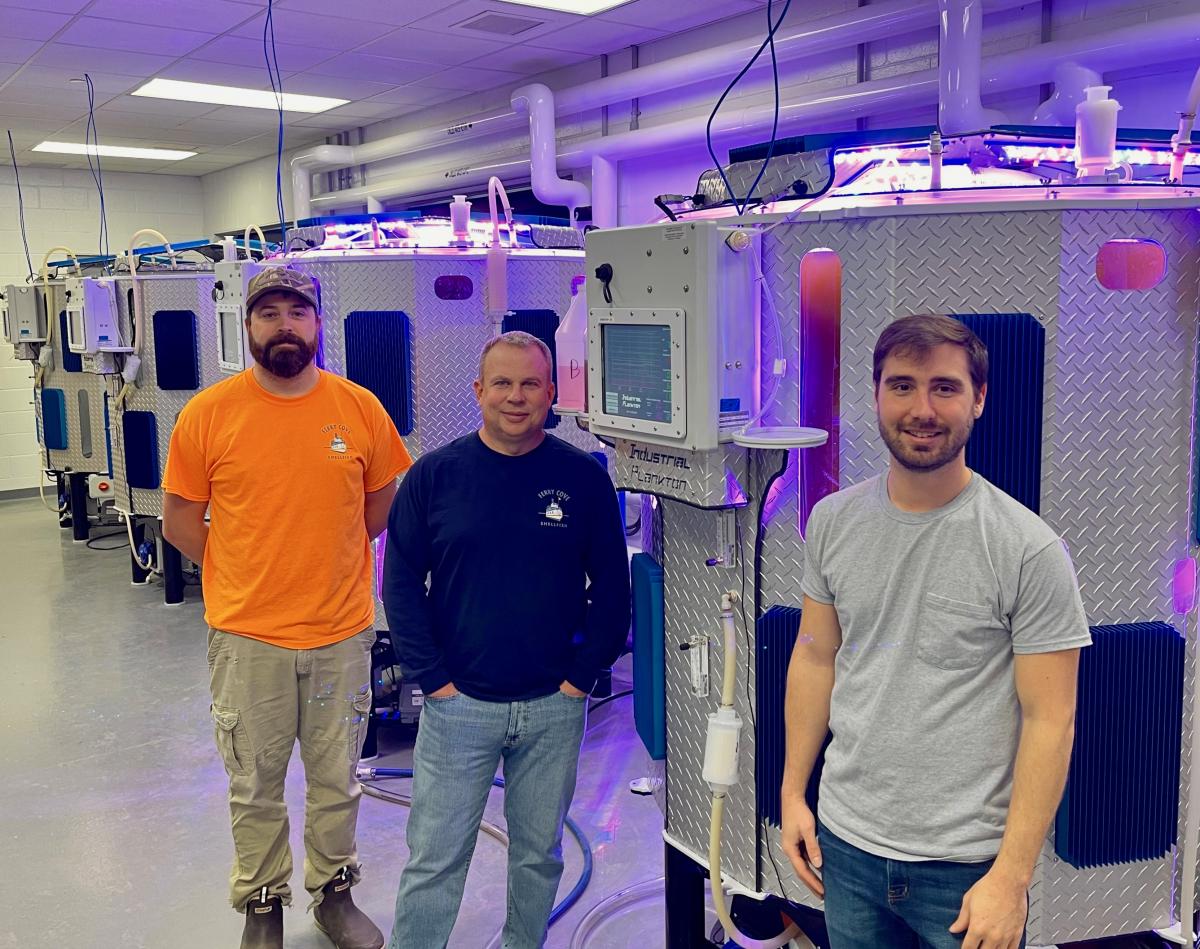

These state-of-the-art algae-production tanks will be providing a steady supply of food to be piped into the oyster seed growing tanks. Shown are (l-r) Steven Weschler, Stephan Abel and Matthew Martin, a phycologist – algae specialist – in charge of managing this component of the operation

Stephan Abel is the driving force behind bringing the private, non-profit Ferry Cove vision to reality. Within weeks of beginning actual production at the sparkling new, multi-million dollar, state-of-the- art oyster hatchery, Abel took time last week to explain the opportunity. His understanding and recognition grew out of years of employment with Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources and the Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery Partnership that started in 1994.

“About 20 years ago there was lengthy discussion about bringing an introduced species of oyster into the Chesapeake to help revive the faltering industry,” said Abel. “Although introduction of a new species – different than the Chesapeake’s native Virginica species – went nowhere for a lot of reasons, part of the review involved a market study of the economic potential for a healthier oyster population. It determined there was enough demand in the market to sell – between Maryland and Virginia – 2.6 million bushels of oysters per year. That number has since doubled to potential sales of about five million bushels per year. Meanwhile the actual annual harvest is stuck at about a million bushels.

“In Maryland,” said Abel, “the biggest hindrance to meeting that potential demand is getting more larvae – seed oysters – to the producers.”

High demand and low supply equals opportunity. That’s the niche Ferry Cove aims to fill.

It’s taken five years, and most importantly the involvement of the Ratcliffe Foundation and its financing, to reach opening day anticipated in January.

Ratcliffe Foundation is a philanthropic funding organization that grew out of successful real estate enterprises on Maryland’s Western Shore. The organization focuses its efforts on enabling students to apply their various educational endeavors through entrepreneurial business ventures. One area of focus has been helping Maryland’s watermen.

Ratcliffe first participated by underwriting a training program at Anne Arundel Community College in 2013 to help watermen get started in aquaculture, specifically for raising oysters on leased bottom in the Chesapeake and its rivers. Then, in 2015, Ratcliffe financed a feasibility study on the need for additional hatchery capacity in Maryland.

Abel said 175 watermen have been trained in aquaculture techniques. Many of them are working their knowledge on approximately 7,000 acres of bottom leased from the state.

“First we focused on getting spat – baby oysters – on shells and growing them out for market. Now training is focusing on how to scale the business.”

The Ferry Cove Shellfish facility is located on 70-acres of land on the shores of the Chesapeake between St. Michaels and Tilghman Island in Talbot County – the historical epicenter of oyster production in the Bay.

Abel’s goal is to supply seed oysters in larvae form to all of those who have been trained in aquaculture. He also plans to make his seed oysters available to the state for planting on wild beds of oysters as part of the public fishery. “The state uses money collected from commercial license fees and from a piece of harvest dollars to buy shells, spat on shells, and seed oysters.” The various county watermen’s associations suggest where the shell and seed should go. Having more larvae available to attach to the shells or other material on the bottom – known as cultch – starts in the hatchery.

Abel said the Ferry Cove hatchery has the capacity to produce two to three billion eyed larvae per year. Oyster larvae develop what is known as an eyespot which detects light and helps guide them to the bottom of the water column when they are ready to eventually attach themselves and grow into the bivalve creatures that most of us know.

“That eye spot on the larvae is a good indicator that they’re getting ready to set.”

It’s that stage when the developing oysters become viable seed, ready for packaging and sale to various public and private growers.

Getting to that stage, though, is what the Ferry Cove operation is all about.

Inside the new, highly energy-efficient facility along the main road between St. Michaels and Tilghman Island, and only a couple hundred yards from the lapping waves of the body of water from which the facility takes its name, a dizzying maze of non-corrosive plastic pipes, industrial fiberglass tanks, quietly whirring pumps, processing tables, and computer monitors has taken shape over the past 18 months. With various colored LED readouts, the screens show a wide variety of data related to temperature, pressure and salinity in the carefully constructed and maintained water environment in which the oysters grow.

“The two major costs in an oyster hatchery are staff and energy,” said Abel. “That’s why we built this facility to LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards and why we incorporated all of this computer technology. The computer technology will allow us to operate this facility with six people, augmented in the busy summer growing season with high school interns. The system allows us to monitor operations and adjust controls from our phones, from anywhere. Traditional oyster hatcheries are far more labor intensive than this.”

Abel said Ferry Cove will hire watermen to harvest and supply brood oysters from local waters. “This area around the Choptank River is historically the epicenter for natural oyster production in the Chesapeake. That’s one of the main reasons we decided to locate where we did. Water conditions and quality here are ideal and we will be pumping a lot of that in for our operation. If, however, there is some event – like a big storm that radically alters the salinity levels we need – we also have a back-up system of tanks where we will be keeping a supply of properly calibrated water to use during the time the natural system restores.”

Brood oysters will be kept in a complex of tanks where they will be conditioned to the water in the facility. Wild oysters begin to reproduce when water temperature rises to between 77 and 90 degrees. Brood oysters will be kept in water at about 68 degrees until the facility operators are ready to move them to spawning tables where the eggs from female oysters are fertilized by the sperm from male oysters. Gradually raising the water temperature of the water will trigger the reproduction.

The fertile eggs – by the hundreds of million – will then be moved into a next set of static – non water-flowing – tanks where they hatch and will be fed with carefully calibrated doses of algae produced on site.

“Our electronic dosing through the piping system will allow us to match our algae production with consumption by the oysters,” said Abel. “Super efficient, like precision farming.”

When those hatched larvae reach a certain size, they are moved to a different set of tanks where algae-enriched water flows around them and they continue their growth until the eye spots begin to develop.

“That’s when we have to pay much closer attention and keep our eyes on them,” said Steven Weschler, a trained biologist and hatchery manager. “That’s when they become animals and it’s all about husbandry. When we see those eye spots get larger and darken, we know it’s time to drain the tanks and gather the larvae before they begin their metamorphosis and attach to the tank.”

The larvae will be gathered, kept moist in clumps about the size of baseballs, and then refrigerated before delivery to producers, followed by a further setting process before deployment on leased bottom and wild bars. “They’ll be ready to sink to the bottom at that point and attach to whatever hard material – ideally shell – that is there,” said Weschler.

If it sounds complex, it’s because it is. But it’s designed for success by a team of experienced oyster scientists, engineers, hatchery operators and installers.

Abel and Weschler plan to turn the key on the design in January when the first brood stock will come in for two months of conditioning followed by two weeks of larval production.

“We should have oyster seed to sell in about three months,” said Abel. “By April or earlier. Once the demand for the seed starts in the spring, we’ll keep right on producing until September. We have to get the spat to a certain size to survive the winter.”

Abel said the state requires holders of leased bottom for aquaculture to plant oysters on a certain percentage of their holdings each year. “It’s a use it or lose it situation,” said Abel. “But up to now there’s been no availability.”

That’s the problem Ferry Cove aims to address.

This time next year should tell whether the new hatchery can produce the two to three billion additional seed oysters annually it projects, and whether Ferry Cove’s grand vision can help all of the Chesapeake’s watermen close the considerable gap between market potential and current harvest levels while realizing all of the many associated benefits.

Dennis Forney grew up on the Chester River in Chestertown. After graduating Oberlin College, he returned to the Shore where he wrote for the Queen Anne’s Record Observer, the Bay Times, the Star Democrat, and the Watermen’s Gazette. He moved to Lewes, Delaware in 1975 with his wife Becky where they lived for 45 years, raising their family and enjoying the saltwater life. Forney and Trish Vernon founded the Cape Gazette, a community newspaper serving eastern Sussex County, in 1993, where he served as publisher until 2020. He continues to write for the Cape Gazette as publisher emeritus and expanded his Delmarva footprint in 2020 with a move to Bozman in Talbot County.

Photos by Dennis Forney

Jay Corvan says

I’m very Glad to see this plant coming on line. I was a part of the early planning for this project. A few responsible citizens Banding together to address a serious problem of water quality in the bay and actually DO something without a lot of government help ( help that’s usually either To late too

Top heavy to deal with complex issues. Here’s an instance where private enterprise can solve social problems.