“You know, I’m not an artist, I’m a journalist.”

By Jeff McGuiness

Photography by Dave Harp

“You know, I’m not an artist, I’m a journalist.” A statement like that would be given little attention if said by most anyone, but Dave Harp is not just anyone. Coming from him, the unquestioned dean of the college of Chesapeake photographers, someone whose career in Bay imagery spans six decades and has raised him to a place in the profession all his own, that statement is a stunner. Dave Harp may not see himself as an accomplished artist, but most everyone else does. A Maryland governor did and placed him on the Maryland State Arts Council. Loyola College did and presented him with the Andrew White Medal. Johns Hopkins did and published three of his photobooks.

Several of Dave Harp’s works of art can now be seen at an exhibition at the Dorchester Center for the Arts in Cambridge, a retrospective of his oeuvre first seen at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum and then Salisbury University. Harp made many of the images on display in Dorchester beginning in 1976. If you missed the first two events, the Cambridge exhibition running through September 25th is a must see.

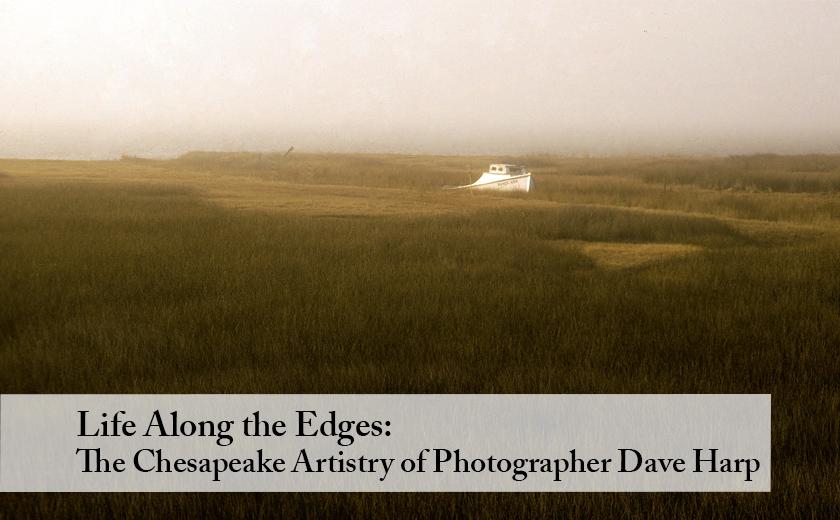

Few have Dave Harp’s gift for capturing the beauty, poetry, moods, and drama of the Chesapeake region and his grit to pursue it. Just look at some of his photographs.

The image above is a misty fall morning along the Nanticoke River at Chicone Creek with Jerusalem artichokes flowering in the foreground. To me, it is not a photograph as much as a meditation. Feel stressed? Sit quietly in a chair breathing evenly and stare at every element of the scene until you are at one with it. At that point, a feeling of peace will envelope you.

Or Harp’s photograph from the late 1980’s of a fleet of working skipjacks catching the icy light of a windless November sunrise on first day of dredging season, an iconic image of a bygone era.

But not all his work depicts blissful scenes. It includes imagery of the constant fight for survival on the Chesapeake, both economic and physical, such as his representation of workboats blown about like discarded flotsam along the boiling seas around the Chesapeake Bay Bridge—Tunnel. It is reminiscent of Gericault’s, “The Raft of the Medusa” hanging in the Louvre, only Dave Harp’s image is not the scene of a shipwreck. It is a portrayal of how watermen chose to work every day in the lower Chesapeake in the gales of winter back when dredging for crabs was legal in Virginia. And it explains why Dave Harp sees himself as a journalist.

His desire is not to create pretty pictures, but to communicate something special about life along the edges of the Chesapeake. He seeks to tell a story and do so using artful photography. He talks about the decisive moment, that point in time that may arrive with little effort on his part, but more often is the culmination of days of obsessing over how to achieve it. The gathering of facts to reach an understanding of the subject matter. The previsualization to serve as a guide to an idea that may or may not be validated once on scene.

But most of the time, it is about the waiting. Not just waiting for the heron to lift off the water into the snowfall of a winter storm, but waiting for the light, always influenced by a myriad of factors, to finally get itself right. For Dave, that’s something typically happening early in the morning or in the hour or so before sunset.

Or it can be waiting for bad weather because Dave believes “Bad weather makes great photographs.” It was bad weather that led to the photograph of the Virginia crab dredgers, one he made when taking a break from heaving overboard whatever was in his stomach that morning. And it was bad weather that led to his portrait of deckhand Lewis Phillips huddled in the tiny cabin of a working skipjack on a cold blustery day in January, replete with the rubber band Phillips used to hold his glasses in place when he leaned over to cull oysters.

Now that he is 75, Harp has the luxury of reflecting on how his approach to his art/journalism has evolved since his days as a kid with a camera playing along the Potomac River near Williamsport, Maryland. It was a Huck Finn existence, but because his rafts always sank, he turned to the family business of journalism and eventually arrived at the Baltimore Sun for what he described as a dream job. Back then, the Sun Magazine was more than a regular paycheck with benefits. It was a generous travel budget and assignments that allowed him to travel extensively and gave him broad latitude to follow his muse. All he had to do was concentrate on his photography.

As the years went by, he began seeing that management wanted to move him into management, and what Dave loves to do is be out there, in the guts, high up the creeks along the Bay’s edges where nature thrives, chasing the light coming in sideways through the wet morning grass. Harp describes himself as an “outside dog,” happiest paddling a kayak in the fog of a Chesapeake swamp with camera at the ready. He decided to leave the Sun and go freelance, never looking back. Soon, his work was appearing in dozens of publications including The New York Times, Smithsonian, Audubon, Sierra, Natural History, Travel Holiday, and Coastal Living.

Harp’s approach to his craft is guided by Elliott Erwitt’s observation that photography is not only an art of observation, “It has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.” He began his photographic pursuit of the Chesapeake fascinated by the cultures so different from his boyhood in the Maryland foothills, now focusing on the people who lived alongside and worked the Bay’s waters. As the years went by, he began understanding the multiple constituencies within those cultures, each interacting with the others, each with a different perspective, each having its own set of ambitions and needs. What motived Dave was gaining a better understanding of those constituencies—plant and animal as well as human—and then communicating how they relate to one another along the edges of their societies.

That philosophy is reflected in his photography. A graveyard now underwater as the edges of the Bay shift over time.

Jamie Marshall as a high schooler wondering if there was life beyond the shores of Smith Island and working the water as his family had done for generations.

His mother Mary Ada seemingly overwhelmed by all those layers of Smith Island cake so much in demand.

A way of life struggling to survive as we humans, striving for security, constantly meddle with a fragile world.

Today, Dave Harp spends as much time creating videos as he does still imagery. It began one day when his writing buddy, Tom Horton with whom he has collaborated on several books of essays and photographs, pulled him into a project with filmmaker Sandy Cannon-Brown. Dave went along reluctantly and was idly passing the time shooting a series of stills when Sandy said, “You know, there is another button on that camera you might want to try.” He did, and with that the three of them launched a joint venture that has produced five videos with a sixth in the works. All have been aired on public television multiple times and downloaded tens of thousands of times from the Bay Journal’s website where Dave now serves as staff photographer.

Harp remains wedded to still imagery, but he believes his videos are a more direct and powerful way to communicate. Even so, he applies all the expertise he has developed over the years from still photography—the obsessing, planning, and most of all waiting—to arrive at that decisive moment to create his new perspective. But it’s not that he is reworking subjects already treated. He sees his role as bringing fresh perspectives to our ever-changing world, one Dave Harp believes we should do far more to cherish.

The exhibition “Where Land and Water Meet: The Chesapeake Bay Photography of David W. Harp” can be seen at the Dorchester Center for the Arts in Cambridge, MD from Friday, August 5 through Sunday, September 25th. The Dorchester Center is located at 321 High Street, Cambridge, MD. Additional information can be found here.

Dave Harp’s videos with Sandy Cannon-Brown and Tom Horton can be found here and downloaded free of charge.

Jeff McGuiness was the senior partner of a public policy law firm based in Washington, DC, and founder of HR Policy Association. A fine arts major in college who served as a photographer in the Air Force during the Vietnam War Era, he has picked up where he left off 50 years ago with Bay Photographic Works. He lives in St. Michaels, MD.

Steve Lingeman says

Thank you Jeff for such a excellent story about Dave Harp. Every word is well placed and expresses so much about Dave. However, one aspect of Dave’s personality not stressed in your story is Daves generosity.

Last year Dave an I started discussing portrait photography, reportage photography and the work he did at the Baltimore Sun. I explained the project I was starting (The Humans of Talbot County), and that even though I have been a serious photographer for over 20 years, I had little portrait experience.

Dave volunteered to show me the ropes, loaned me equipment and got me started down the road on this project in a humble and generous manner. Thank you Dave.

Debbi Dodson says

Such a great read, Jeff!

Jeff McGuiness says

Steve, I couldn’t agree with you more. Dave is one great guy. Jeff

Paul Fine says

Being a photographer I want to say I’ve always admired Dave’s work. He, in my eyes is, as it says, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Dank you Dave for sharing your talent with all of us!

Debbi Dodson says

Such a great read, Jeff!

Mary Hunt-Miller says

Wow! Just amazing, beautiful images!