Emma Amos (1937-2020) was born into a middle-class African-American family in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father owned a drugstore. He knew writer Zora Neale Hurston and artist Hale Woodruff. Emma’s mother was an alumna of Fisk University in Nashville. Emma grew up in cultural environment, and she began to make art at the age of six. She attended a segregated high school, and she received a BFA degree in printmaking from Antioch College. Her fourth year in college was spent at the Central School of Art in London in 1958. She commented, “Even though Atlanta and most cities during my youth were segregated, the art schools, and smart creative people were beacons of light. The city was a good place for black people with big dreams, and it continues to be a major site for black colleges, business, artists, and political figures. It is important to me to point out that both of my college-educated parents had fathers who were both slaves.”

Amos moved to New York City and began working in two printmaking studios: Letterio Capalai and Robert Blackburn’s Printing Workshop. However, her applications to museums, galleries, and schools all resulted in the same response: “We’re not hiring right now.” She began working with weaver Dorothy Liebes, developing designs for unique carpets. In 1960 Amos met Hale Woodruff, who became a life-long friend and mentor and introduced her to SPIRAL, a collaborative founded by Woodruff, Romare Bearden, and others. Amos was the first and only woman member of SPIRAL. She continued her education and received her MA from New York University in1966. She married Robert Levine in1956, and they had two children. While the children were little, Amos made small paintings, weavings, quilts, and illustrations for Sesame Street magazine. She became an assistant professor at the Mason Groves School of Art at Rutgers University in 1980. She was tenured in 1992, served as chair of the Visual Arts department from 2005 until 2007, and retired in 2008.

Feminism was flourishing in the 1980’s. Amos rejected what she knew about it: “From what I heard of feminist discussion in the park, the experience of black women of any class were left out. I came from a line of working women who were not only mothers, but breadwinners, cultured, educated, and who had been treated as equals by their black husbands. I felt I could not afford to spend precious time away from studio and family to listen to stories so far removed from my own.” However, her attitude changed when she participated in the women’s group Heresies, founded by New York women artists of all colors: “All my distain for white feminist disappeared, because we were all in the same boat. We just came to the boat from different spaces.”

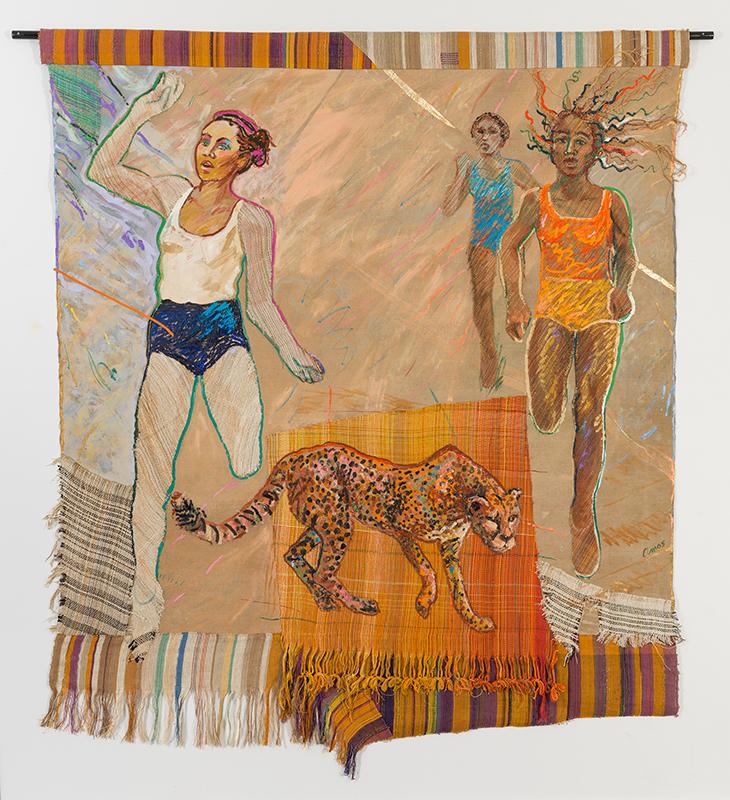

Amos’s series Athletes and Animals (1983-85) depicts African-American, sports figures, swimmers, and runners painted with lions, cheetahs, and crocodiles. “Runners with Cheetah” (1983) came from her interest in politics and the feminist art movement. Three women runners, one white and two African-American, are in motion, racing toward an unseen finish line. From the feminist point of view, the women are running to catch up with men. The cheetah, the fastest land animal and an endangered species, represents the discriminatory and racist belief that Black people are animals. Amos commented, “I want to make clear the relationship between artists, athletes, entertainers, and thinkers and the prowess, ferocity, steadfastness, and dynamism of animals.”

Amos returned to her roots with the use of fabrics. “Runner with Cheetah” is part acrylic paint and part collage. In this work Amos has incorporate fabrics into the composition and as borders. The borders are striped Kente cloth woven in West Africa for thousands of years. There are numerous Kente designs, and each color and pattern has a specific meaning. For example, gold stripes represent royalty and maroon stripes mother earth. By adding fabrics as frames, Amos also challenges the idea that art and craft are separate and that craft is a lesser form.

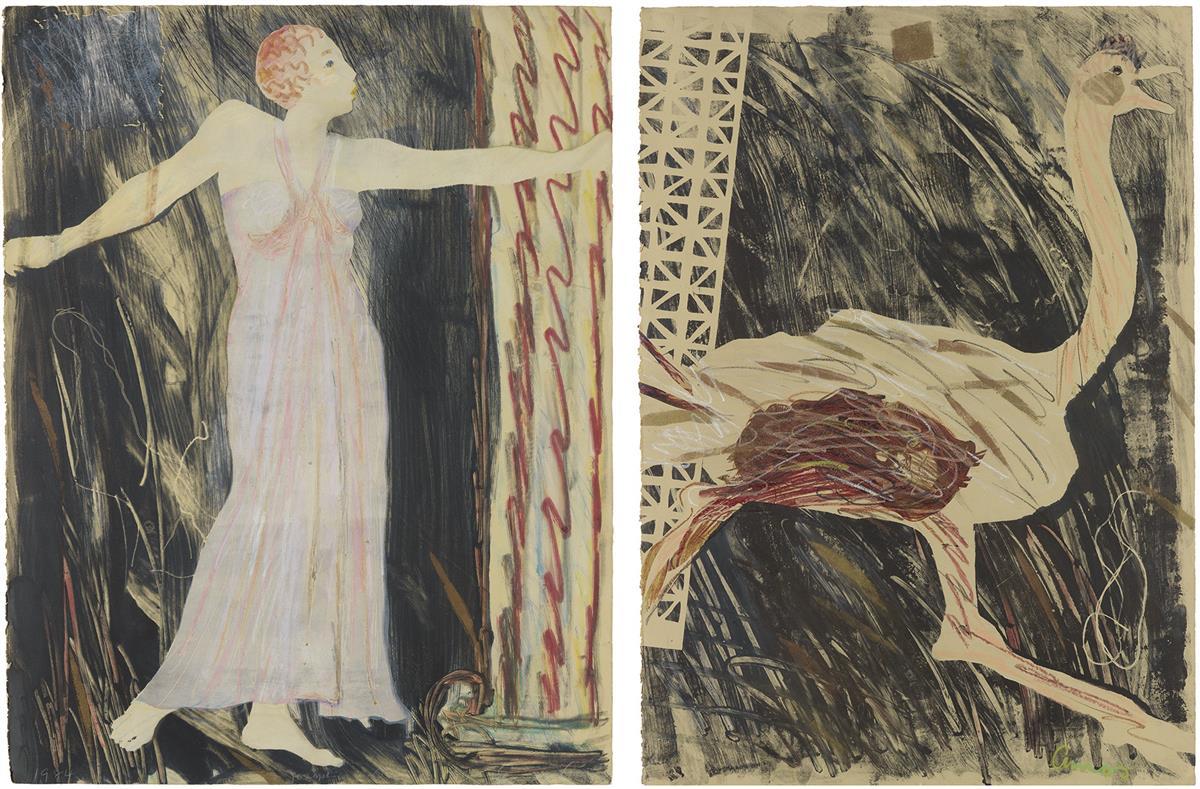

“Josephine and Her Ostrich” (1985) (44” x30”) is part of the Athletes and Animals series. Josephine Baker, the famous African-American dancer and singer, wowed European audiences in the 1920’s and later. Photographs of her riding through the streets of Berlin in a cart drawn by an ostrich (1926) inspired this print. The work is a black ink monoprint enhanced by drawing on the image with pastels. Baker and the ostrich are side by side. Comparing the artistic dance of Baker with the awkwardness of the ostrich, Amos asks the viewer to think again about racial stereotypes.

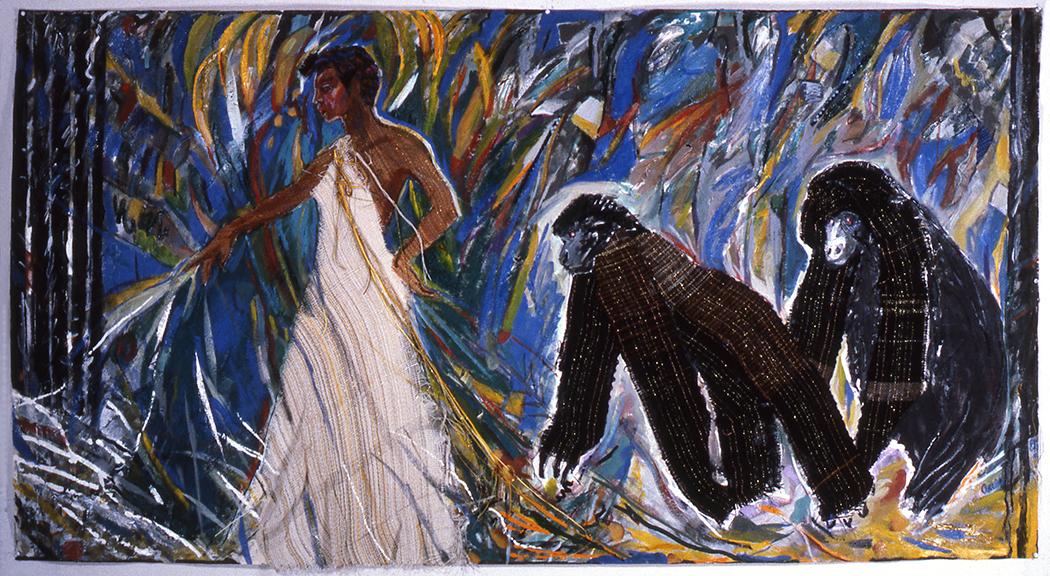

In “Josephine and the Mountain Gorillas” (1985) (48” x90”) (acrylic with hand woven fabric) (Athletes and Animals), Amos challenges the male Abstract Expressionists who dominated the art world. She created an abstract painting for the background. In front is the graceful image of Baker. Two black gorillas docilly follow her. Their faces are cut from a photograph and their bodies are composed mostly of hand-woven fabric. Choosing a well-known figure such as Baker, Amos gives the viewer another chance to contemplate racial stereotyping and discrimination.

Baker was adored and honored in Europe, but unwelcome in America. A life-long advocate for racial equality, Baker spoke at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Coincidentally, Baker kept a cheetah and a chimpanzee as pets.

A group of New York women artists founded in 1985 the Guerilla Girls to fight sexism and racism in the art world. They made posters, wrote articles, put up billboards, staged protests, and made public appearances wearing gorilla masks. Emma Amos was one of them. They kept members’ names secret, using the names of famous women artists instead.

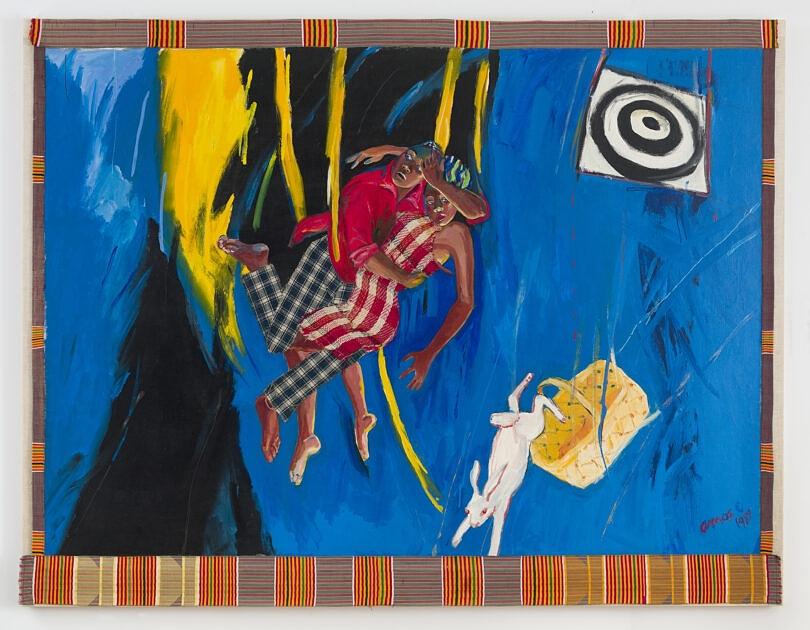

Amos began the series Falling in the 1990’s. The images relate to her personal anxieties, the economic crisis of the Reagan era, and her fear about America’s future. In “Targets” (1992) (57×73’’) (acrylic and fabric) figures fall, slip, and slide, and objects hurl through an abstract space. A man and woman cling to each other as they fall. The figures are partially painted and their jazzy clothing is boldly patterned hand-woven fabric. A target is painted at the upper right side of the work. A white rabbit and a basket fall at the lower right. Amos uses well-known symbols from popular culture in many of her paintings. Perhaps the white rabbit is the one from Alice in Wonderland, and the basket looks much like the one Dorothy carried in the Wizard of Oz. The painting is framed with African Kente cloth.

In “Equals” (1992) (76”x 82”) (acrylic and fabric), a self-portrait, Amos hurls through space in front of the red and white stripes of a waving American flag. Gold stars fly with her, some containing white stars outlined in black and others with open eyes in the center. The blue of the flag at the lower right is painted in the style of Pollock with drips of gold and black paint. At the upper left is a photograph of a share cropper’s cabin taken by Amos’s relative during the Depression. The sharecropper system was known as “slavery by another name.” Amos’s portrait at the lower right provides compositional balance to the photograph. A large red equal sign is at the center of the composition.

Amos is posed with her right hand turned back as if to say the past is past and she will not go back. However, her left hand turns forward; she wants to come into the future but is not sure what it will hold. Equality is what she wants. Her facial expression had been interpreted as one of determination. The Kente cloth frame is printed with portraits of Malcolm X. Spike Lee’s film about Malcolm X’s life and fight for racial equality was made in 1992.

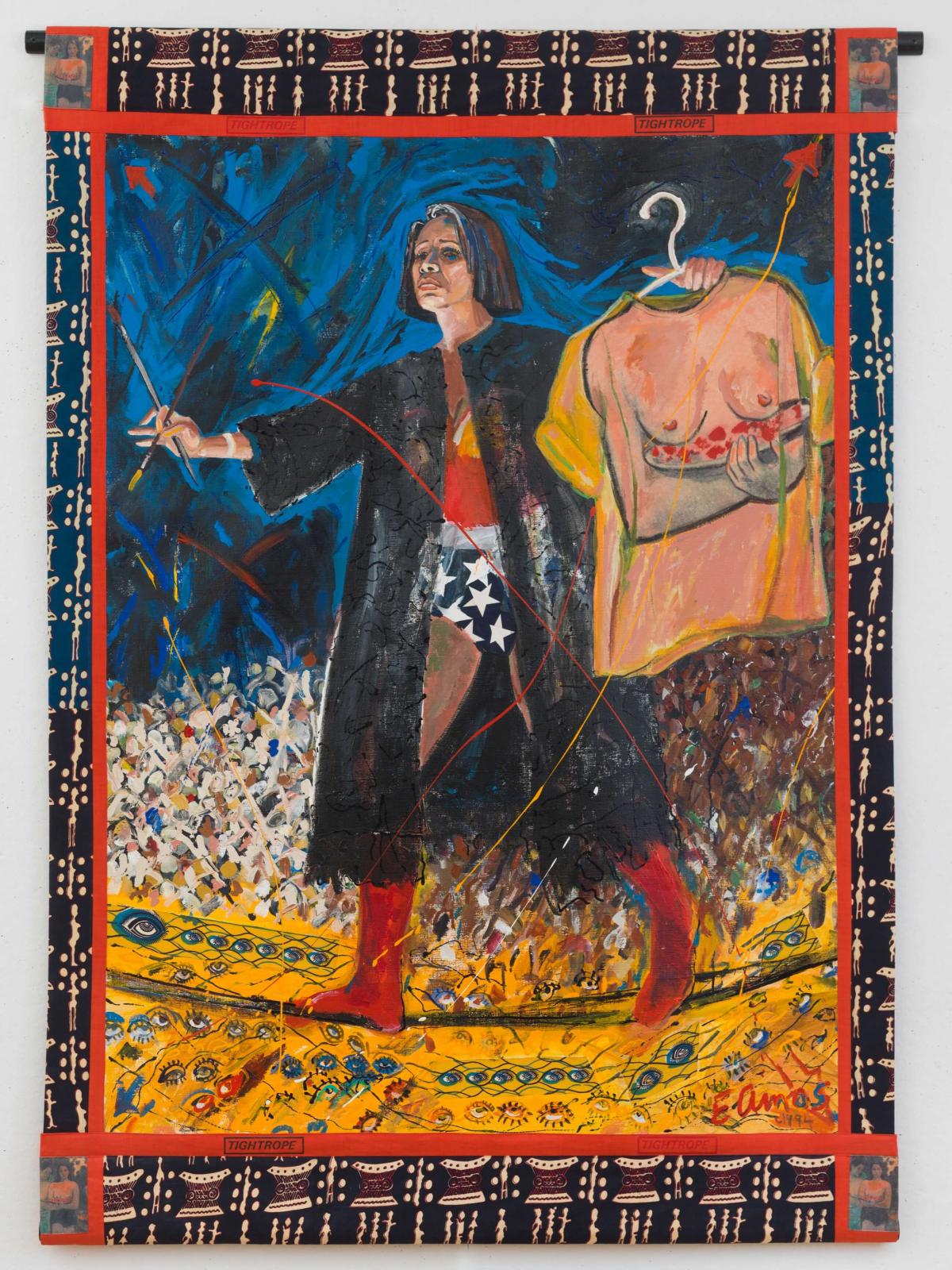

“Tightrope” (1994) (82’’ x 58”) (acrylic and fabric) depicts Amos balancing on a tightrope. The issues that many women face are displayed. She is a mother, wife, artist, and business woman, all of the roles she had to juggle. She is dressed as Wonder Woman, wearing red boots and blue shorts with white stars. In her right hand are her paint brushes. In her left is a T-shirt imprinted with a painting by Gauguin of his 13-year-old mistress, bare-chested and carrying a bowl of fruit. Not a fan of Gauguin’s life style, Amos felt either she was a sex object that provided for all of a man’s needs, or she wished to go to an island paradise.

Beneath the tightrope a sea of eyes watches her perform. Behind her a blue sky is painted in the Abstract Expressionist style. The painting is bordered with African fabric. Gauguin’s painting is printed on each corner.

On January 20, 2009, Barack Obama was inaugurated as the 44th President of the United States. “Higher and Higher” (2009) (68.5” x135”) celebrates this historic event in the history of America and of African-Americans. The first panel of the triptych depicts black slaves picking cotton. Slaves climb up a rope out of the fields. The words JACOBS LADDER is painted in red across the field. The middle panel depicts a strong black man entering the 20th Century, leaving the cotton fields behind. An African-American woman dressed in red runs vigorously toward the future. Beneath her, four African-American drummers lead a parade of people of various ages, dressed in contemporary clothing. The white frame of a window flies above her. It is a window into the future. In the third panel, a contemporary African-American woman dressed in shorts and white running shoes, a smile on her face, runs past the White House. A painter’s palette is split between the second and third panels, and a woman in T-shirt and jeans jumps for joy. The last figure is a woman posed as many of Amos’s falling figures with her arms wide spread and knees bent in a jumping pose. She smiles widely. She literally “jumps for joy.”

Emma Amos died on May 20, 2020, after a battle with Alzheimer’s disease. Art News, a prominent magazine for the arts, praised Amos’s contributions: [She] “profoundly shifted the course of art history through her various experiments combining painting and textiles, exploded with color, new meditations on what figurative painting could be, and issues of race and gender.” (4-30-2021)

“I try to make painting resonate in some kind of way. It’s always been my contention, that for me, a black woman artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.” (Emma Amos).

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Harriette Lowery says

Thank you, thank you for this awesome article!