Impressionist artist Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) was from a wealthy Parisienne family. He grew up near the area of the St. Lazarre train station. He received a law degree in 1868 and a license to practice law in 1870. During the Franco-Prussian War, he served in the Garde Nationale Mobile de la Seine. As a result of a visit in 1871 with Leon Bonnat, who was a painter, art collector, and professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Caillebotte changed direction and began to study art. His talent was evident, and within a short time, he set up his own studio in his parent’s house. His father died in 1874 and his mother in 1878, leaving Gustave and his two brothers very wealthy. They moved into an apartment on the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris.

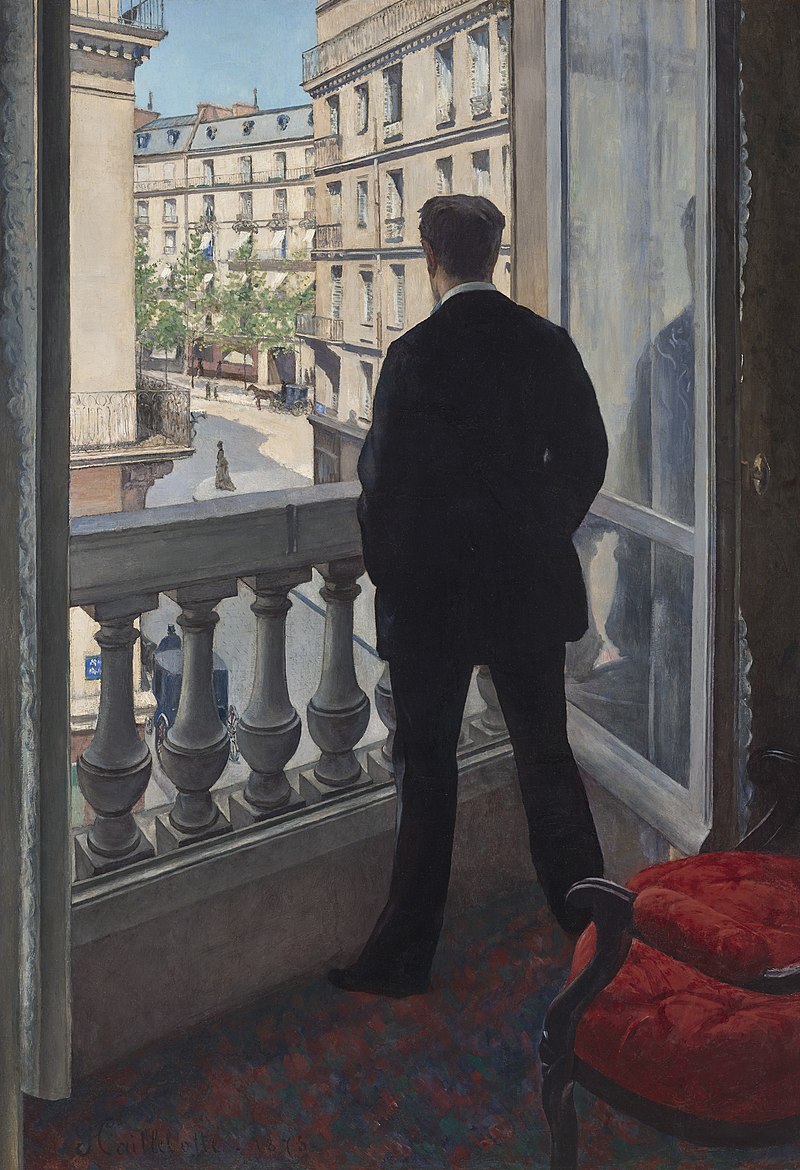

“Young Man at the Window” (1876)

“Young Man at the Window” (1876) (32”x46”) depicts Caillebotte’s brother Rene, standing on the balcony of one of the new apartments on rue de Miromesnil and overlooking the Boulevard Haussmann. The apartment is luxurious, with a colonnaded balcony rail, large glass windows that are open, a carpet with deep red and blue flowers, and a handsome carved chair with rich red upholstery. These details indicate wealth.

Caillebotte was fascinated with the new architecture of Paris, instituted during the period of 1853 until 1870 by Baron George-Eugene Hassmann. He was commissioned by Emperor Napoleon III to tear down the overcrowded, unhealthy slums and to build a more spacious and hygienic Paris. His reorganization resulted in wide boulevards that connected the various parts of Paris and new buildings with mansard roofs and dormer windows that allowed greater light into the rooms. The roof and windows in this work were a signature of Haussmann’s buildings. New squares, sewers, fountains, aqueducts, and parks were constructed. The view out the window includes the wider avenues and sidewalks and new buildings that stretch into the distance. This new Paris became one of Caillebotte’s favorite subjects.

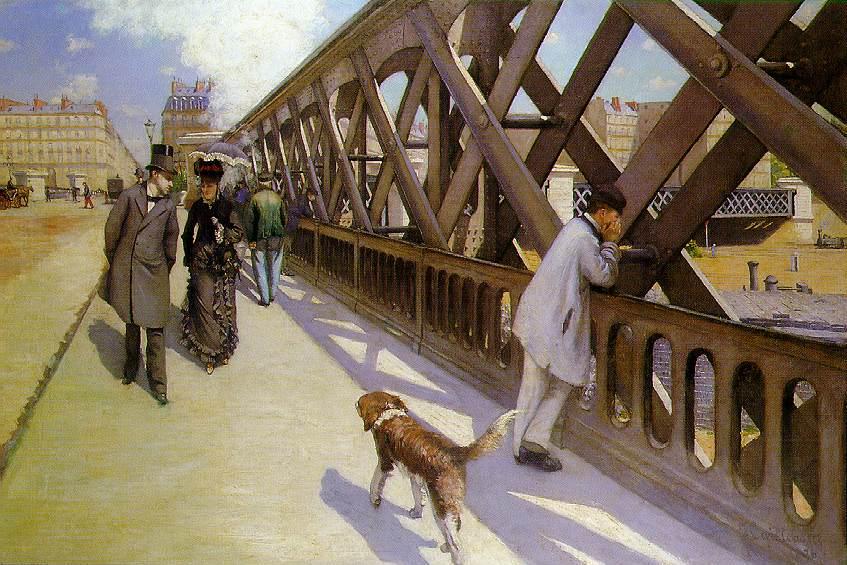

“Le Pont de l’Europe” (1876)

In January 1877, Monet, Sisley, Degas, Manet, and Renoir met in Caillebotte’s apartment on rue de Miromesnil to plan a third exhibition of the Impressionist group. “Le Pont de l’Europe” (1876) (49”x71”) was one of Caillebotte’s paintings included in the exhibition, and it was one of the stars of the show. The large bridge off the plaza was one of Haussmann’s renovations. It connected six avenues named after a European capital, and it spanned the railroad yard of the Gare Saint-Lazare. The view is from the Avenue of Vienna. Construction of railways, bridges, and train stations, the result of the invention of the steam engine, was taking place across Europe.

Caillebotte made several preliminary sketches for the painting, adjusting the perspective and the placement of the people. He paid careful attention to the construction of the bridge trusses. Caillebotte, like Millais, was interested in the common people, and he included at the front of the painting a worker looking out from the bridge. A dog leads the viewer into the composition. A well-dressed man wearing a hat and a woman in black stroll along the bridge. This young woman is often considered a prostitute, because women in public, especially at train stations, was against the social norm of the time. The man is thought to be Caillebotte and his companion Anne-Maris Hagen. Caillebotte remained single.

Also in the exhibition was Monet’s “Le Pont de l’Europe, Gare Saint-Lazare,” an alternate view of the bridge. Monet and Caillebotte were great friends. Caillebotte purchased a Monet painting in 1874, and left 16 Monet works to the State in his will. He was not only a painter in the group, but also a patron. His wealth made it possible to support the other members by purchasing their work and providing any necessary funds to support group efforts.

“Skiffs” (1877)

Caillebotte came to Monet’s attention through his paintings of rowers, swimmers, and fishermen, created at his family estate at Yerres, a small town southeast of Paris. Both men were boaters, and Caillebotte also designed boats. They also discovered they were avid gardeners. Cailebotte’s “Skiffs” (1877) (35”x46”) is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. It is one of several of his paintings of boats from 1877 until 1878. He was interested in everything that was going on in the art world, and his Impressionist instinct about color is evident. He uses fresh blues, greens, and yellows, and he painted with broad brush strokes to depict moving water. In “Skiffs” it is a sunny day, and the shadows across the rowers’ white tee-shirts are blue, not gray. The yellow coloring of the oars, hats, and sunlight on the water help to emphasize the rapid movements of the rowers.

He continues to display his interest in perspective that was influenced by his keen interest in photography and Japanese prints. His tendency to crop and zoom-in is demonstrated in the work. He places the view slightly above the rowers so the perspective hides their faces. Skiffs are flat bottomed boats that easily tip over if not handled correctly. The energy Caillebotte creates in this painting helps the viewer to experience the challenge faced by the rowers.

“The Uphill Path, Chemin Montant” (1881)

In May of 1881, the Caillebotte brothers bought land on the Seine at Gennevilliers and built a holiday home they named Petit Gennevilliers. It was a popular sea-side resort in Argenteuil and Trouville. Caillebotte picked and chose from realism and Impressionist styles. “The Uphill Path, Chemin Montant” (1881) (39”x49’’) demonstrates that he had fully embraced Impressionist color and brushwork. The couple enjoy a leisurely stroll along a garden path on a sunny day. The sky is a bright blue. A dark orange parasol and a straw hat protect the couple who are at present on a shady part of the path, but will walk into the sunlight. Broad brush strokes of green, dark blue, yellow, and light green paint create a rich grassy lawn, with shadows crossing it from the trees on the right. The doorway to the Italian style villa is at the left. The color of the woman’s parasol, the villa’s shutters and brick walls, and a section of wall farther along the path draw the viewer’s attention deeper into the garden. Caillebotte’s unique sense of perspective is highlighted by the diagonal line of the house’s cement fence and the molding along its second story. The garden ends in a bright yellow sunlit patch of grass and a green hedge. This work was sold for $6.73 million at Christie’s in New York in 2003, and in 2019 for $22.1 million at Christie’s in London.

“Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers” (1893)

Caillebotte stopped showing his work in 1884, and he dedicated his time to gardening. “Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers” (1893) (39”x24’’) (Metropolitan Museum, New York City) is one of the many paintings he made of his garden and of flowers. Like other artists, he made still-life paintings, many of cuts of meat and fish, and some of flowers. Chrysanthemums were popular in Europe and France because of their variety of colors, as can be seen in this painting. The flowers also were popular because of their association with Japan. Chrysanthemums were symbols of longevity and the Japanese imperial family. This close-up composition is the result of his idea of decorating the panels of dining room doors with images of plants, an idea shared with his close friend Monet. His paintings included long paths of dahlias and sunflowers. He also grew orchids.

Caillebotte in his greenhouse at Petit Gennevilliers (1892) (photograph)

Caillebotte maintained over the years close connections with several of the Impressionists. Renoir often came to stay at Petit-Genneviliers, and he served as the executor of Caillebotte’s will. Many of Caillebotte’s 500 paintings are in private collections. When he died in 1894 at the early age of 45, he left 68 paintings to the French government. They were not his own, but works he had purchased over the years to support Monet (14), Cezanne (5), Degas (7), Renoir (10), Sisley (9), Manet (4), Pissarro (19), and Millet and others. The Impressionists still were not welcomed in French museums. Caillebotte stipulated the paintings were to be shown in the Luxembourg Palace, where the works of living artists were displayed. As executor, Renoir ultimately negotiated that 38 of the works would be shown at the Palace. The near-sighted French government had rejected the offer for the donation of the rest of the collection again in 1904 and 1908. The government finally accepted the donation in 1928, but it was too late. Other claimants had emerged and the paintings were sold.

Caillebotte’s works were not popular, because he did not need to exhibit his work. His reputation was based upon his support of the arts. His popularity and international fame as an artist are the result of the 2024 exhibition of his works at the Musee d’Orsay in Paris and the exhibition in 2025 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

If he had lived instead of dying prematurely, he would have enjoyed the same upturn in fortunes as we did, for he was full of talent. He was as gifted as he was conscientious, and when we lost him, he was still at the beginning of his career. (Claude Monet)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.