Jacques-Joseph Tissot (1836-1902) was a successful painter and printmaker in the 19th Century. Born in Nantes, a port city in France, he would continue throughout his life to be interested in painting images with ships. His parents Marcel Tissot, a successful drapery merchant, and milliner Marie Durand influenced his interest in fashion and art. He decided by age 17 to become an artist, and by age 20 he was in Paris studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He learned to paint in the classical style. Hippolyte Flandrin, a well-respected Academic painter, was his major instructor. Tissot met life-long friends in Paris, among them Whistler, Manet, Oscar Wilde, and Degas, who became his mentor. He had success at the Paris Salon in 1859 with his paintings based on the popular story of Faust. Gounod’s opera Faust and Carre’s play Faust and Marguerite influenced the works. Tissot’s earlier works featuring medieval stories were considered by critics to be of the old style. Critic Paul de Saint-Victor wrote, “It is sad to see an intelligent and gifted artist betraying his talent with pedantic imitations.”

“Two Sisters” (1863)

“Two Sisters” (1863) (83’’x54’’) is characteristic of Tissot’s meticulous attention to detail. The two sisters stand on a grassy lawn beneath the trees. The older sister’s white gown has a sheer layer of fabric decorated with laces draped over the well-fitted gown. Her red hair ribbon, red flowers tucked into her black ribbon belt, and black hat with red feathers are well matched. The younger sister’s white pinafore, appropriate for her age, has just the right amount of ruffles and lace. The younger sister carries a round fancy basket that repeats the shape and colors of the hat. Fashion seems to be the subject of the painting. The sisters appear to be posing, revealing little of themselves.

“Mlle L.L. in Red” (1864)

Tissot showed “Two Sisters” and “Mlle L.L. in Red” (1864) (49”x39”) for the first time at the Paris Salon of 1864 to illustrate his competency in depicting contemporary images. “Mlle L.L. in Red” is a mystery. The subject remains unidentified. Her red jacket was worn by the Zouaves, a French corps of soldiers formed in Algeria, who continued to wear their North African style uniform. The rows of bright red pom poms caught attention. Her lap and legs are merely suggested under the voluminous black skirt. Complementing her red jacket are the dark green color of the carpet and the red and green colors played out in the wall paper and the fabric covering of the chair. The subject appears to be a reader; she has books and loose papers in her room. The mirror behind her reflects an open door, and a card or photograph is tucked into the frame of the mirror. Charming and mysterious, she engages the viewer in a nonchalant manner.

However, in 1864, another critic commented that Tissot created “genuine paintings…whose greatest merit consists in the sincerity of their modern feeling.” In Le Grande Journal, Jules Castagnay wrote, “Mr. Tissot, the crazy primitive of the most recent Salons, has suddenly changed his manner and moved closer to Mr. Courbet, a good mark for Mr. Tissot.”

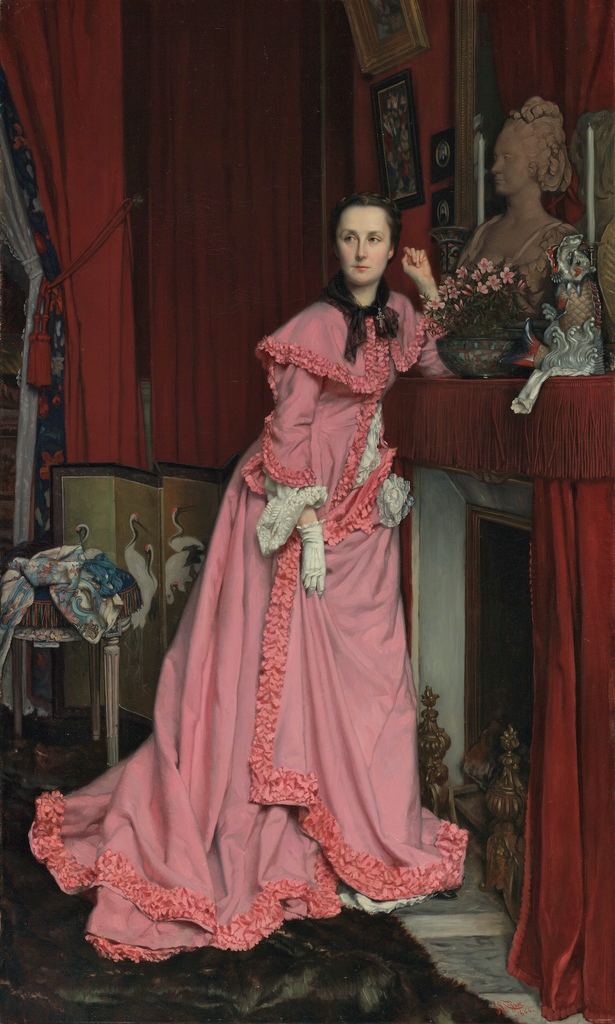

“Portrait of the Marquise de Maramon” (1866)

“Portrait of the Marquise de Maramon” (1866) (50”x38’’) is one of many portrait commissions received by Tissot. This portrait of the wealthy Marquise is more intimate than the group portrait of the family (1865). The setting is in their Chateau du Paulhac in Auvergne, France. Dressed in a deep pink peignoir, with rows of ruffles, the Marquise stands on a dark fur rug and leans on the fireplace mantle. She turns her head as if to recognize someone in the room. A black scarf with a small silver cross is tied around her neck. The cross is a small item, certainly placed there by her choice for a personal reason.

The room is lush. Red velvet drapery hangs from the fireplace and the window. It is evening. The candles on the mantle do not cast much light. The color of the bowl of flowers on the mantle, the same color as her gown, is designed to repeat the color of the gown. The portrait bust calls attention to the family’s nobility. A ceramic Japanese dragon rising from waves sits on a white glove, the mate to the glove that the Marquise is wearing, another touch that adds a mystery. The Louis XVI stool with needlework placed on top indicates she is a lady of leisure. Tissot borrowed this painting from the Marquis to show it at the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris.

Tissot, like many Parisians, was fascinated with Japanese art and artifacts, and he was among the great collectors of them. He included a Japanese folding screen and a Japanese ceramic in the painting. English Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, visiting Paris in November 1864, wrote to his mother that he had purchased four Japanese books and on visiting Madame Desoye’s shop on the Rue de Rivoli “found all the costumes there were being snapped up by a French artist, Tissot, who it seems is doing three Japanese pictures, which the mistress of the shop described to me as the three wonders of the world, evidently in her opinion quite throwing Whistler into the shade.” In 1869, French art critic and novelist Champfleury wrote about Tissot’s passion: “The latest original event of note is the opening of a Japanese studio by a young painter with sufficient means to afford a small townhouse on the Champs-Élysées.” Tissot also was the drawing master for Prince Tokugawa Akitake, the brother of the last Shogun and leader of the Japanese delegation to Paris in 1867-68.

Tissot served on the French side in the Franco-Prussian War and later with the Paris Commune during the resistance. After the war in 1871, he traveled to London, where he remained for the next eleven years. He learned etching and drew cartoons and caricatures. He was employed by Thomas Bowles, the editor of Vanity Fair magazine. His work was shown at the Royal Academy in London under his pseudonym Coide. Tissot purchased a house in St John’s Wood, popular with British artists. The writer and art critic Edmond de Goncourt described it as “a studio with a waiting room where, at all times, there is iced champagne at the disposal of visitors.”

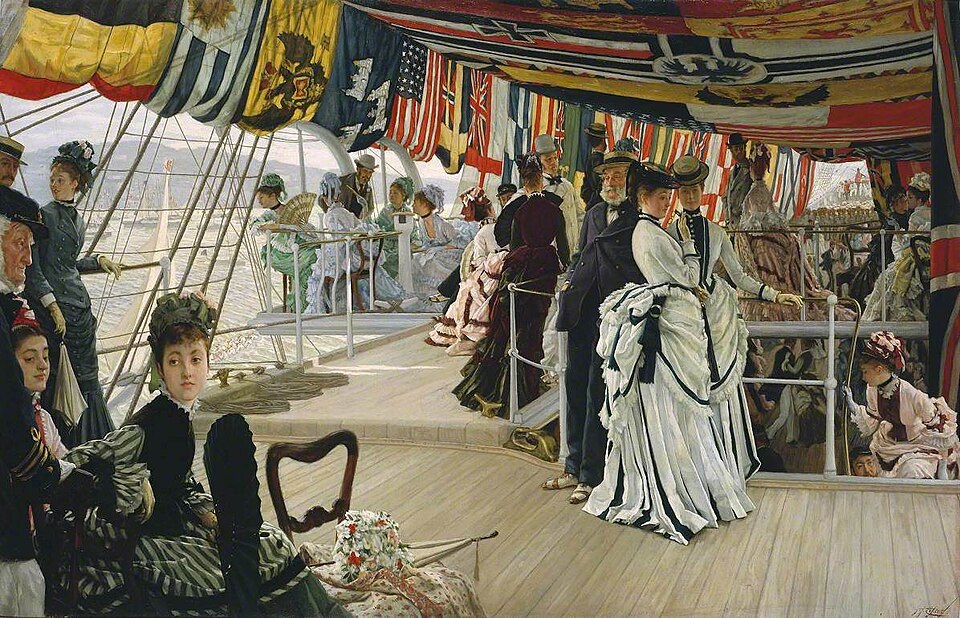

“The Ball on Shipboard” (1874)

Tissot believed London would be a source of patrons with money. He became a member of the Art Club in 1873. The member artists were popular with the wealthy industrialists of the day. The Industrial Revolution was changing the economy from hand-made to machine-made. From 1760 to 1830, iron and steel production, trains and ships powered by steam, use of electricity, use of machines in the production of goods, and advances in communication changed Britain and Europe. Tissot’s love of the sea, which he shared with Whistler, his interest in fashion, and his talent for storytelling communicated through his paintings appealed to numerous patrons.

“The Ball on Shipboard” (1874) (51”x33”) combines several of his interests. A variety of national flags are sewn together as an awning. People are enjoying a sunny day. Many of them are beautiful young women dressed fashionably. Some walk about the deck, some sit in mixed company groups, and others go below deck. It is interesting to note that most of the men are older.

Tissot continued to paint images of society, and the sale of his paintings added to his wealth. However, critiques were mixed. John Ruskin described Tissot’s paintings as “mere painted photographs of vulgar society.” The writer of an article in The Athenaeum said there were “no pretty women, but a set of showy rather than elegant costumes, some few graceful, but more ungraceful attitudes, and not a lady in a score of female figures.” Another critic found the piece “garish and almost repellent.” Despite the British Victorian prudishness, prominent art dealer William Agnew, purchased “The Ball on Shipboard” and easily sold it for a nice profit.

Degas invited Tissot to show his work in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. Tissot refused, but remained friends with Degas and Manet and others of the Impressionist group

“The Gallery of the HMS Calcutta, Portsmouth” (1876)

Victorian society was gender-segregated, which resulted in social and sexual tensions. Tissot represented this tension in “The Gallery of the HMS Calcutta, Portsmouth” (1876) Both women are dressed in white, a popular color choice at the time, and their dresses are decorated with bows and ribbons. The hourglass figure is achieved with a tight bodice over a corset. The woman with yellow bows holds a large fan in front of her face, not looking at the junior naval officer and the woman next to him. Fans were used for secret messages. An open fan at the left ear meant “do not betray our secret.”

Curves are plentiful in Tissot’s composition, from the curves of the ladies to the curves of the wicker chairs on deck. Even the shape of ship’s gallery, a type of balcony at the back of a ship that houses the officers’ quarters, is curved. Questions about motives and relationships abound.

American-British writer Henry James, whose novels often told the story of marital situations between English and Europeans, described the painting as “hard, vulgar and banal.” Another critic suggested Tissot chose to name the ship Calcutta because it was a play on words from the French “Quel cul tu as” (What an arse you have). The painting was exhibited in 1877 and was sold to Johon Robertson Reid, a Scots painter who became president of the Society of British Artists in 1886.

There may be another reason the ship was named Calcutta. It was a second-rate British ship of the line with 84 guns. Built in Bombay in 1831, it was recommissioned to serve in the Crimean War in the Baltic. It also served from 1856 until 1858 in the second opium war in the Far East. In 1858, Calcutta was the first ship of the line to visit Japan.

Tissot met the Irish beauty Kathleen Newton in 1875, and the couple formed a strong relationship until her death from tuberculosis in 1880. Since she was a divorced Irish Catholic, they could not marry. However, they lived together openly and had a son, Cecil George Newton (b.1878). Kathleen was Tissot’s lover, companion, and muse. She was frequently a female figure in his paintings. After her death, Tissot sold the London house and moved back to Paris. He became interested in spiritualism, popular at the time, and even held a séance.

“Artists and their Wives” (1885)

“Artists and their Wives” (1885) (58’’x40’’) is a depiction of well-known painters and sculptors attending the celebratory lunch on Varnishing Day at the restaurant Le Doyen in Paris. Varnishing day was the day before the opening of the Paris Salon when artists put the final coat of varnish onto their paintings. The artists and their friends could then view the exhibition privately before it was opened to the public the next day. The painting was exhibited at two solo exhibitions, in Paris in 1885 and in London in 1886.

After the death of Kathleen, Tissot painted a series of 15 paintings titled “The Women of Paris” (1885). A Roman Catholic, he also turned his attention to religion. He began a series of paintings that he believed told the truth of the Bible stories of the life of Christ. He traveled to the Holy Land several times between 1886 and 1896. He produced 365 watercolor images, of which 270 were published in a book that became a bestseller. After finishing the project, he began a series of pictures based on Old Testament stories. He died before he could finish the project.

After 11 years in London, Tissot never surrendered his French citizenship. One of his biographers described him “the most English of all French painters.”

The writer of an article in the journal L’Artiste (1869) concluded, “While our industrial and artistic creations may perish, and our customs and our costumes may fall into oblivion, a painting by Mr. Tissot will be enough for archaeologists of the future to reconstruct our era.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.