Cherokee artist Kay WalkingStick was born in 1935 in Syracuse, New York. Her father was Scots/Irish and her mother was of the Cherokee tribe in Oklahoma. WalkingStick began making art at an early age. She graduated in 1959 from Beaver College in Pennsylvania where she earned her BFA degree. She completed her MFA degree at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York City. She served from1988 until 2005 as a tenured Associate Professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. She commented, “It was always important to me to be recognized as a Native person…It was also important to be understood as a New York artist, one who was working in the mainstream.”

”Where are the Generations, Stillness” (1991)

“Where are the Generations, Stillness” (1991) (28”x56’’) (acrylic, copper, and oil on canvas) is an example of WalkingStick’s early paintings in which she adapted the diptych, two separate panels hinged together. She said, “The diptych is an especially powerful metaphor to express the beauty and power of uniting the disparate and this makes it particularly attractive to those of us who are biracial…I use landscape as the context…one side of the painting represents immediately visual memory; the other archetype memory and both could be a stand-in for the human body and soul.”

The left panel of “Where are the Generations, Stillness” is abstract. At the middle of the composition an ochre half oval is surrounded by a sapphire field. The interpretation of abstract images is left to the viewers, but the title of this work offers a suggestion: the semi-oval could be half an egg, symbolic of life. The universe and creation are suggested by the sky, including the red sparks, and the red shape lying beneath the oval, the beginning of the Indian Nations. A barren mountain landscape is on the right panel; no people are present.

Text is printed on the wall next to the painting: “In 1492, we were twenty million. Now, we are two million. Where are the generations, never born? From a distance, the sphere becomes more prominent–a universe, suggesting that viewers would need the perspective of time and distance to understand the weight of genocide.”

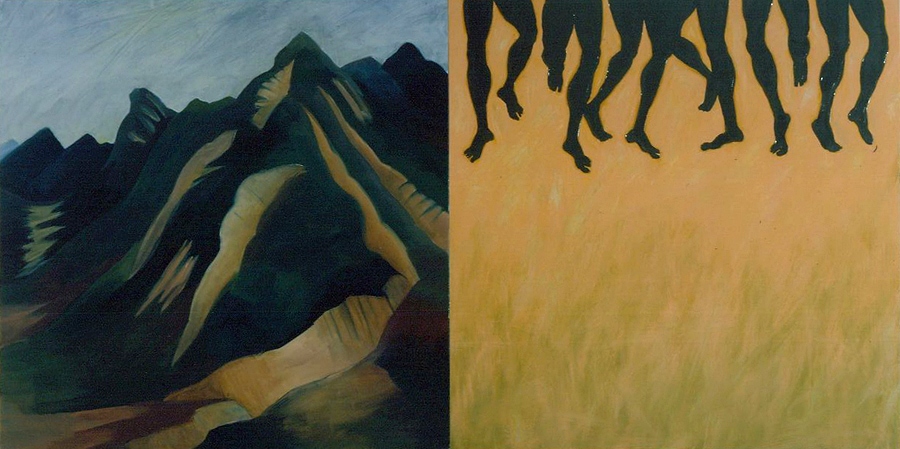

We’re Still Dancing (2006)

In “We’re Still Dancing” (2006) (32’’x64’’), WalkingStick pairs a dramatic image of a rocky mountain with women’s legs dancing on a golden field. The two images create a dynamic duo of hope. The paintings may appear to be alla prima, an Italian term meaning at first attempt. They are, in her words, “by contrast, deliberate and resolved.” They are from “memory, sketches, photos, not a depiction of a specific space, but a psychological state painting of a totally real place.”

“Fairwell to the Smokies” (2007)

WalkingStick painted “Fairwell to the Smokies” (2007) (36”x72’’) after a visit to the Smoky Mountains. It represents the Trail of Tears, when the Indian Removal Act in 1830 forced five tribes, including the Cherokee, to leave their homes in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee. They walked 800 miles west of the Mississippi to Oklahoma. The landscape is painted in rich browns and greens. The Indians walk along the bottom of the canvas. The small size of the figures and hazy gray color make it easy to miss them, particularly those who enter the unknown new land at the right. Text placed on the wall of the gallery explained that Walkingstick, although born and raised in New York, felt the significance of the Trail of Tears when she visited her ancestral homeland in the Carolinas and Tennessee: “It’s about the traumatic experience of leaving home—leaving this beautiful home.”

Stories of the Indians who walked the Trail of Tears are hard to hear. Families were separated, the elderly and sick were forced to leave at gunpoint, and they were given no real time to gather their possessions. After they left, white people looted the homes. Gold was discovered in 1830 on Cherokee lands in Georgia.

“Lush Life” (2015)

“Lush Life” (2015) (36”x72”) represents another facet of Walkingstick’s paintings. She commented, “The move seemed inevitable. Although, I hadn’t put depictions of humans into my art for many years. In fact, their absence had seemed crucial to the significance of the work.” The female figure was herself, and she began using the image on a limited scale in the 1990s. Placing her figure against a lush light green landscape and coordinating the trees with the movement of her dancing legs, gives the viewer a peaceful and happy moment.

WalkingStick was given a retrospective exhibition in 2015 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC. She commented, “I had to come to terms with this idea that I am as much my father’s daughter as my mother’s…I hope viewers will leave the museum with a renewed sense of how beautiful and precious our planet is with the realization that those of us living in the Western Hemisphere are all living on Indian Territory”

“New Hampshire Coast” (2020)

WalkingStick grew up on the East Coast, but she has painted landscapes from coast to coast. She lives and works in Pennsylvania, and she has traveled across the American west and to Italy. In “New Hampshire Coast” (2020) (36”x72’’) she expresses her love of landscape painting in the wide expanse of the Atlantic Ocean and New Hampshire’s rocky coast. The Indian sign, painted in terra cotta on the right side of the diptych, is from a Native basket motif of the Wabanaki Indians, who lived there for hundreds of years before white settlers arrived. A fight for the ownership of the land is an on-going battle in Maine.

“Niagara” (2020)

“Niagara” (2020) (36”x72”) is a painting of one of America’s best-known landmarks. Walkingstick depicts a panoramic view of two of the three falls, Horseshoe and Bridal Veil. WalkingStick has chosen to paint single-view landscapes in her recent diptychs. She painted a symbol of the Haudenosaunee Indians, people of the long house. They are the first Confederation of the Six Nations, also called the Iroquois Confederation, that included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora tribes. They are the oldest participatory democracy in America. Several of their democratic principles were adopted by the thirteen original colonies. The six tribes originally lived in northern New York.

Kay WalkingStick’s work has been included in numerous solo and group exhibitions. Her paintings were exhibited by the New York Historical Society from October 2023 until April 2024, comparing her landscapes with those of the Hudson River School of the 19th Century. WalkingStick was included in the 60th anniversary of the Venice Biennale, that will end on November 24, 2024. The theme of the Biennale was Foreigners Every Where. The Addison Gallery in Andover, Massachusetts is exhibiting her work from September 14, 2024 until February 2, 2025. Kay WalkingStick is one of the most esteemed American Indian artists.

“I want them to also see the primary message in the work, that is: This is our beloved land no matter who walks here, no matter who “owns” it. This is our land. Recognize us and honor this land.” (Kay WalkingStick, 2012)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.