Rosa Bonheur grew up in a unique family. Her father Oscar Raymond was a painter, art teacher, and director of the Ecole Gratitide de Dessin des Jeunes Filles. He also was a devout Saint Simonian, a Nineteenth Century religious group that believed in equality for women and wanted to abolish the class system. Rosa’s mother Sophie taught her to play the piano. All the Bonheur children were artists: Auguste a painter, Isadore a sculptor, Juliette a painter, and Rosa.

The Bonheurs were frequently juried into the Academy Salon Exhibitions in Paris. These exhibitions were held annually and consisted of approximately 5000 works. All entrants were juried unless they were Academy members. Art galleries did not exist, and Salon exhibitions provided the only means for artists to display their works before the public. Salon exhibitions were open to the public and were widely attended. Rosa’s first Salon success was at the age of nineteen in 1841; where she exhibited “Goats and Sheep” (1840) and “Two Rabbits Nibbling on Carrots” (1840). She had six works in the 1845 Salon. In the Salon of 1848, all of the Bonheur family was represented and Rosa won a Third Prize. After this, Rosa stopped creating bronze animal sculptures so as not to compete with her brother Isadore.

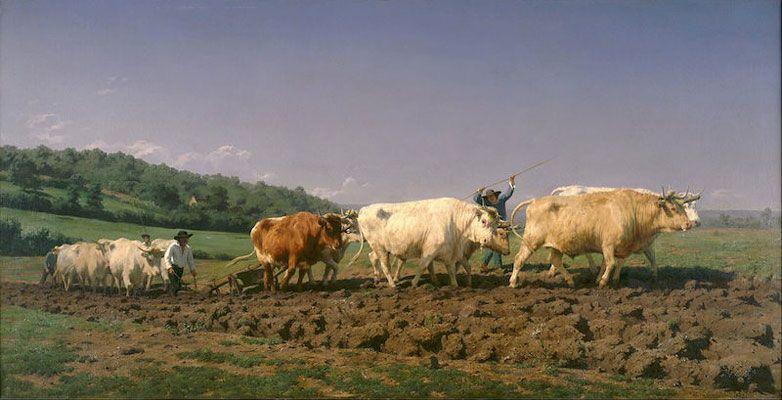

Bonheur’s first Salon gold medal work was “Plowers at Nivernais” (1849) (5’9’’ x 8’8’’). The Academy painter Horace Vernet presented her with a Sevres vase as the prize, and the art critic Theophill Thore remarked “Mademoiselle Rosa paints almost like a man.” The painting was unlike any animal paintings done by male artists. Bonheur was determined to understand the animals she painted, not simply to present a superficial likeness of a good looking animal. As a child she was interested in animals, kept pets, and went into nearby parks, fields, woods, and farms to observe living animals. She had a pet sheep that was kept on the balcony of the family’s sixth floor walk-up apartment. Having decided on her subject matter, she was determined to observe and understand them in all aspects of their lives. To attain a complete knowledge of the animals, she went to slaughter houses, watched butchering, and studied working animals.

“Plowers at Nivernais” depicts hard working cattle pulling plows through rich dark brown earth. Prodded by the workers, who take second place in the painting, the animal’s interesting facial expressions, their powerful muscles, and their drooling can be observed.

In her adventures into the fields and slaughter houses, Bonheur found it easier to wear pants, rather than a skirt. She also smoked, bobbed her hair, wandered the streets alone, wore men’s clothing and eventually owned property. She was fiercely independent. “To [my father’s] doctrines I owe my great and glorious ambition for the sex to which I proudly belong and whose independence I shall defend until my dying day.” Bonheur knew herself well. “As far as males go I only like the bulls I paint.” Early in her life she met Natalie Micas with whom she had a fifty year relationship, and after Micas’ death she enjoyed a relationship with an American artist in Paris, Anna Klumpke. “I well knew that I would lose my independence were I to take on household and wifely duties. I preferred to keep my own name. I believe I have been able to give it some renown.”

“Horse Fair” (1853-55) (8’ x 16 ½ ‘) (Metropolitan Museum) was and is the largest animal painting ever made. Bonheur was thirty-one years old and painted it in sixteen months. Exhibited in the 1855 Salon, the “Horse Fair” earned her the hors concours, the honor of submitting work to the Salon without going through the jury. The painting also won Bonheur, a First class medal that entitled her to receive the Cross of the Legion of Honor, and because of this honor the work would have been purchase by the French government. This did not happen. Bonheur rarely exhibited again in the Salon. She took the painting on tour. “Horse Fair” toured England and was given a special viewing for Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. Engravings were made of the painting and sold throughout Europe and American. There was even a Rosa Bonheur doll, much like the RBG doll. In 1855 at the Exposition International in Paris, Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the painting for $53,000. Theophile Thore and others criticized her work as being too English and Scottish in look, and her paintings after the “Horse Fair” had her “reddish tones, undecided touch, glassy and mannered effect.” This criticism did not interfere with the Bonheur’s growing international reputation, and it did not bother her personally: “The epithets of imbeciles have never bothered me.”

“I care nothing for the fashionable. A portrait painter has need of these things, but not I, who find all that is wanted in my dogs, my horses, my hinds, and my stags of the forest.” In order to continue to paint as she wished, and after several arrests for wearing improper attire, Bonheur stated, “I was forced to recognize that the clothing of my sex was a constant bother. That is why I decided to solicit the authorization to wear men’s clothing from the prefect of police.” She received written permission from the police, but it needed to be renewed every six months, and needed a doctor’s letter stating she needed to wear pants for reasons of health.

“Horse Fair” depicts the Paris horse market, and in the background we see the outline of the Pietie-Salpetrier Hospital. The painting is impressive. The horses are life size and powerful. The attendants have trouble controlling them as they rear, race and exert their strength. Bonheur explained, “The horse is, like man, the most beautiful and most miserable of creatures, only, in the case of man, it is vice or property that makes him ugly. He is responsible for his own decadence, while the horse is only a slave.”

Bonheur painted a wide variety of animals during her career, traveling to difficult locations where she could observe animals in their natural habitat. In “Highland Raid” (1860) (51’’ x 84’’) (National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.), she adeptly captures an overcast and windy day. The sun and the rain are competing as the on-coming storm approaches. The raiders struggle to coral and herd the wild Highland cattle. The powerful bodies of the cattle and sheep, wild eyed and scared, butt against each other, and resist the attempts of the herders. “Highland Raid” was exhibited in the Salon a few weeks before Bonheur died.

Her fame and popularity made it possible for Bonheur, at age 37, to purchase an estate and Chateaux at By near the Forest of Fontainebleau. The acres of pasture at By made it possible for her to gather a collection of deer, elk, ponies, goats, gazelles, and lions. All roamed free on the estate. Her lions followed her everywhere like dogs, but eventually she had to send the lions to the zoo because they frightened people. In 1865 the Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, came to see her at By and awarded her the much delayed Cross of the Legion of Honor and named her an Officer in the Legion of Honor. “I was in the garden and just had time to change from my masculine clothes. Madame, she told me, I bring you a jewel on behalf of the Emperor. His Majesty has authorized me to announce to you your name as chevalier in the imperial order of the Legion of Honor.” Bonheur was the first woman to receive the honor. Many honors followed. Among them were the Cross of San Carlos (1865) from Maximilian and Carlotta of Mexico, Commander in the Order of Isabella the Catholic (1880) from Alfonso of Spain, Catholic Cross and Leopold Cross (1880) from King of Belgium, and Merite des Beaux-Arts de Saxe-Colburg- Gotha of Germany.

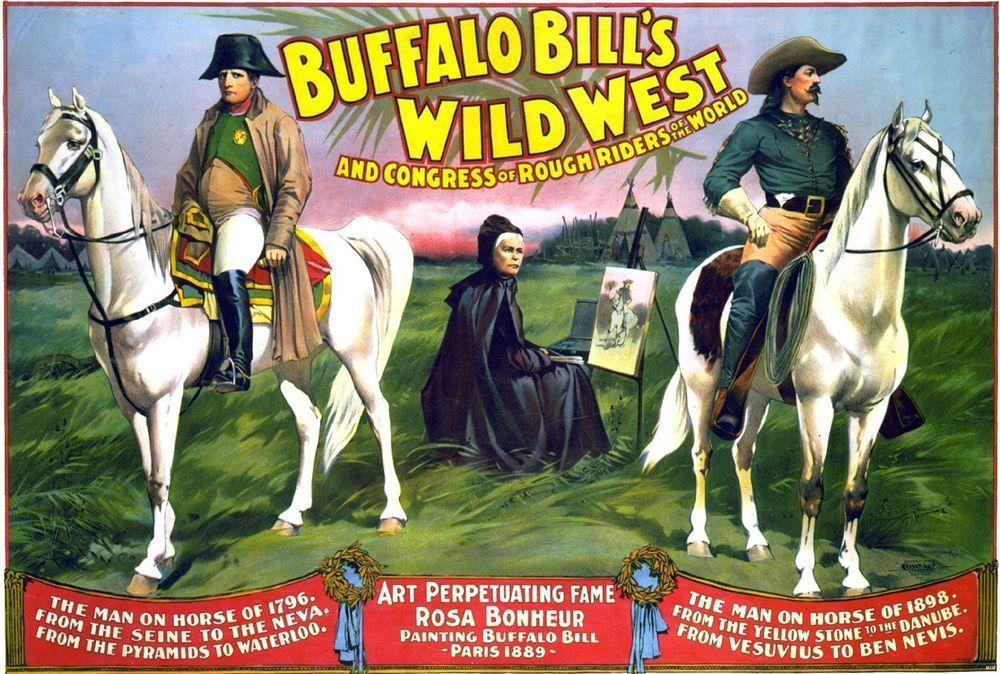

Bonheur had been attracted to the American west after visiting an 1854 exhibition of American Indian paintings by the George Catlin. Her interest was rekindled in 1889 after attending Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show at the Paris Exposition. She invited him to her estate, and they became friends. He invited her to the encampment on 39 acres near the Bois de Boulogne and Eiffel tower. Bonheur made numerous paintings and sketches of everything. The portrait of Cody is small in scale, only 18 by 16 inches, but as with all Bonheur’s work, it seems monumental. She went almost daily to the encampment: “I was thus able to examine their tents at my ease. I was present at family scenes…conversed as best I could with warriors…made studies of the bison, horses and arms. I have a veritable passion, you know, for this unfortunate race and I deplore that it is disappearing before the white usurpers.”

One of the advertisements (1898) for Cody’s show includes images of two famous French persons: Napoleon is “The man on horse of 1796” and Bill Cody is “The man on the horse of 1898”; however, Rosa Bonheur is “Art perpetuating fame, Rose Bonheur, painting Buffalo Bill in 1889”. Bonheur is indeed shown painting the famous painting of Cody. All are situated on a lush green lawn, and cleverly included in the background are army tents behind Napoleon and Indian teepees behind Cody.

Bonheur traveled to American to visit the Women’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. She met the American painter Anna Klumpke, who traveled back to By with her and was her companion until Bonheur’s death in 1899. Klumpke, her administrator, discovered 892 paintings and several boxes of drawings, all sorted and dated. “I wed art. It is my husband, my world, my life dream, the air I breathe. I know nothing else, feel nothing else, and think nothing else.” Bonheur was an exemplary artist.

Bonheur also was an exceptional woman, and her words place her as a feminist precursor. “I have no patience with women who ask permission to think. Let women establish their claims by great and good works, and not by conventions.”

“Why shouldn’t I be proud to be a woman? My father, that enthusiastic apostle of humanity, told me again and again that it was woman’s mission to improve the human race…To his doctrines I owe my great and glorious ambition for the sex to which I proudly belong, whose independence I’ll defend till my dying day. Besides, I’m convinced the future is ours.”

“If American marches at the forefront of modern civilization…it is because of their admirable intelligent manner of bringing up their daughters and the respect for their women.”

This article is dedicated to the life and legacy of the Notorious RGB.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.