Marisol Escobar (Venezuelan/American) began making art in the 1960’s, and she became one of the very popular POP artists along with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. The New York art world changed rapidly from the 1960’s through the 1990’s with styles from Abstract Expressionism, Color School, POP, OP, Minimalism, New Realism, and unnamed others in a constant search for something new. During that same period, America’s politics, wars, economy, and society also changed quickly. Marisol reflected on these changes and found “modern life increasingly disturbing.” In 1969, she left her life and her fame behind to spend a year in Asia, recharging her energy and her thinking. “When I came back [from the far East] I felt like doing something very pure, just for the sake of it.”

Marisol’s art changed from funky and critical POP culture images to thoughtful works dealing with social issues. In “Self-Portrait Viewing the Last Supper” (1982-84) (29’10’’ wide x 10’1’’ high x 5’7’’ deep), Marisol modernized the famous “Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci. She created a three-dimensional wood sculpture of the painting. The figure of Christ is carved from a piece of salvaged brownstone. Each of the thirteen figures is posed in the exact composition found in the painting, and placed in the same setting with four panels on each side, three rear panels, and the food on the table. The arch on the wall over Christ’s head recalls the device da Vinci used to create Christ’s halo.

Christ announces to the seated apostles that one of them will betray Him. Da Vinci’s was an unusual choice, as typical “Last Supper” paintings depicted the offering of bread and wine in what would become the Eucharist ceremony. Da Vinci also was the first to show the various reactions of the apostles to the announcement. Marisol adds one extra figure, herself, seated several feet in front of the table of men. She looks on: “Because I studied it so much, I put my portrait there.”

In many of her sculptures Marisol included self-portraits. She stated, “I began to make self-portraits because working at night I had no other model…I would learn about myself.” Marisol looking on was a statement about the outsider position women were given, and a call to action for equality. The life-sized figures add to the impact. Viewers can walk up to view the scene. They can ignore the female presence in the room. Almost.

Marisol included children in her previous sculptures; some were abandoned and neglected. Marisol was eleven when her mother died, a loss she never forgot. In her new work, she turned to social issues. “Boy with Empty Bowl” (1987) (24”x17”x16”) (pictured), “Mother and Child with Empty Bowl” (1984) (not pictured), and “Poor Family 1” (1987) (not pictured), illustrate her interest in world hunger: “In some parts of the world people are on diets, obese from overeating, while in other parts, people are starving to death. I would like to see a more balanced way of sharing food and life.” Marisol’s “Boy with Empty Bowl” was part of the International Art Show for the End of World Hunger held in 1987. The boy’s life-sized body was made from a log. His legs are crossed and his toes can be seen on either side of his bowl. The knife and fork also are crossed on the empty plate in front of him. “Boy” is armless and therefore cannot feed himself, calling more attention to the fact there is no food to eat. Some have described his face as optimistic?

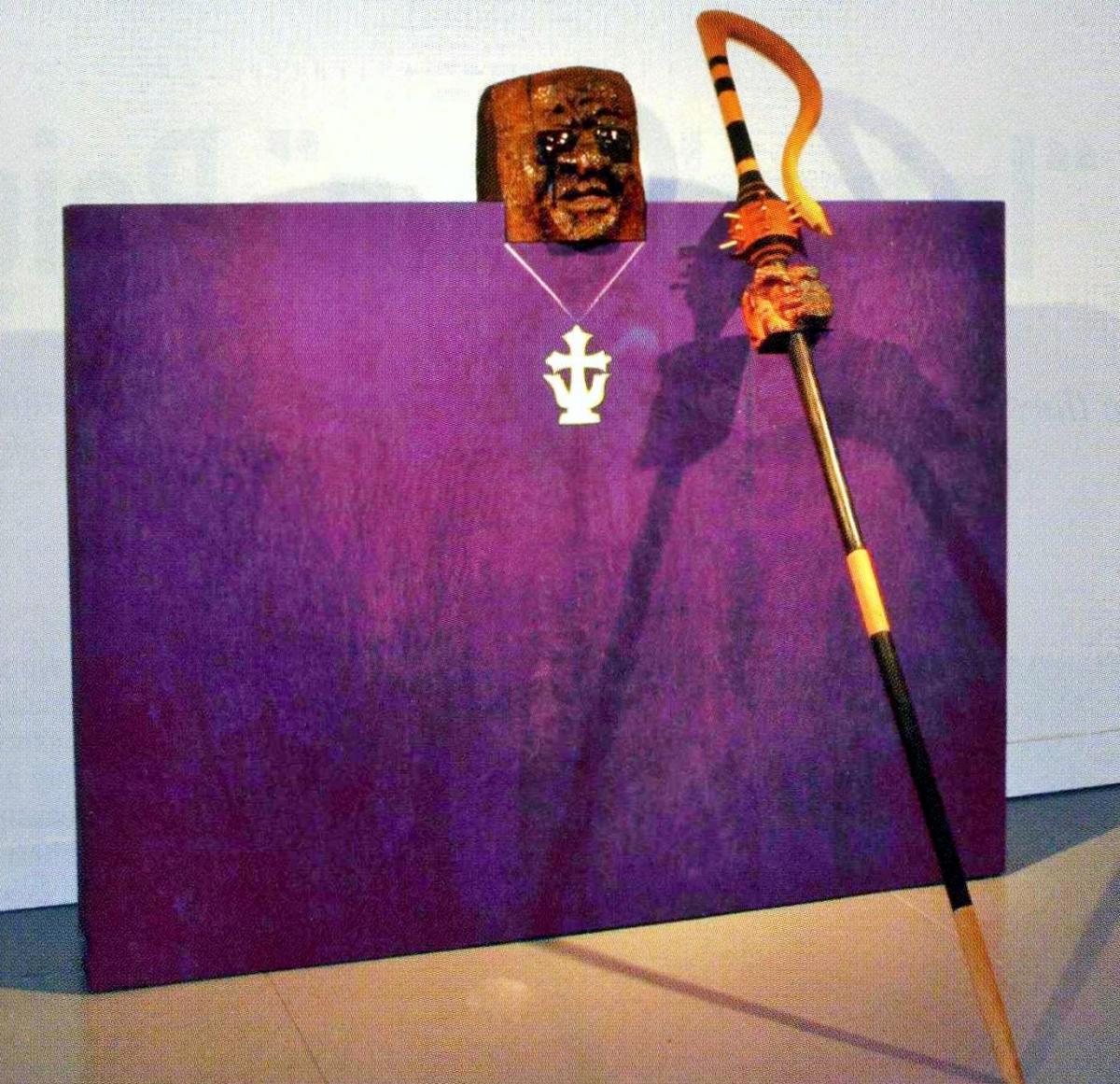

On Marisol’s return from Asia in 1970, she began a series of sculptural portraits of significant people in the arts. All had reached an advanced age. Her memorials to their lives and their work include Georgia O’Keeffe, William Burroughs, and Martha Graham. The sculpture of “Desmond Tutu” (1988) (4’ x 6’) was created four years after he was awarded the Noble Peace Prize for his work against apartheid in South African. Tutu’s carved face sits atop a 4’x6’ piece of plywood, painted purple to represent his clerical robe. A cross is cut out of the plywood where his heart would be, and a light shines through the cross. Tutu’s eyes are shaded with carved sunglasses that are coated with a shiny paint suggesting the reflection of sunlight. His left hand holds the Bishop’s crozier. The sculpture is simple, direct, and powerful.

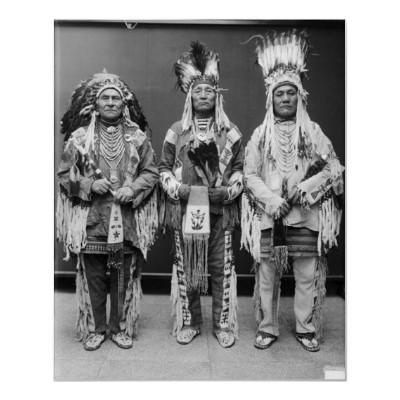

In the 1990’s Marisol began to create drawings and sculptures of Native American figures from old photographs. “The Blackfoot Delegation to Washington in 1916” (1993) was made at the invitation of a group of Native Americans who invited artists to submit artwork for their section of the American Pavilion in 1992 at the World’s Fair in Seville. In exchange for the work of art, the Native Americans offered the artists a shaman’s blessing. Marisol was the only artist who responded.

Marisol used a photograph of three Blackfoot Indians who were in Washington to negotiate a land settlement with the government. The figures in front are carved in wood with ceramic hands. They wear Native clothing with feathered headdresses. The two figures in the back row wear suits and white shirt collars. While the faces of the three figures remain the natural color of the wood, the faces of the two rear figures are covered with white chalk. It was the intention of the government to take the Indian out of the man. All of the Indians appear stiff and solemn. Marisol had the advantage of time, knowing that their mission would fail and their fate would be tragic.

When his son John John was three years old, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. At age eleven, Marisol lost her mother. The loss never left her. Marisol frequently saw the grown John Jr. walking the streets in their Tribeca neighborhood. Inspired by the iconic photograph of John Jr. saluting his father’s funeral cortege, Marisol created “The Funeral” (1996) (56’’x122’’x11’’). The figure of the child towers over the cortege that includes the honor guard, six white horses pulling the flag draped coffin on the caisson, the riderless horse Black Jack, the family, and a troupe of flag-bearing toy soldiers. Marisol’s portrait skills are evident in all her work, but none more so than here. Marisol captures John Jr.’s emotions of confusion, disbelief, and non-comprehension of the event.

Marisol describes her artistic journey: “I was born an artist. Afterwards, I had to explain to everyone just what that meant.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.