The Wampanoag Nation, People of the First Light, comprised as many as sixty-seven villages populated by approximately 40,000 Indians. The Wampanoag joined with the Pilgrims for a three-day celebration sometime between September 21 and November 9 in the year1621. About 90 warriors attended the feast, including the great chief Massasoit. He sent warriors to hunt deer for the feast, including five deer and other game, geese, ducks, and other fowl along with shellfish, nuts, and berries to add to the Pilgrims’ store. There might have been turkeys, but they were not a major part of the meal.

“The American Wild Turkey, Male” (1863)

“The American Wild Turkey, Male” (1863) (26’’x40’’) (print) was plate #1 of the series Birds of America created by James Audubon (1785-1851). The series consisted of 435 plates. He wrote about his choice of the turkey as his first plate in the series in his Ornithological Biography (1831): “The great size and beauty of the Wild Turkey, its value as a delicate and highly prized article of food, and the circumstance of its being the origin of the domestic race now generally dispersed over both continents, render it one of the most interesting of the birds indigenous to the United States of America.” Audubon rendered images in great detail. In order to achieve a precise image, he prepared the birds, carefully stuffing and placing them. Audubon gave the turkey a proud stance and rich coloring. The plant behind the turkey is a cane plant.

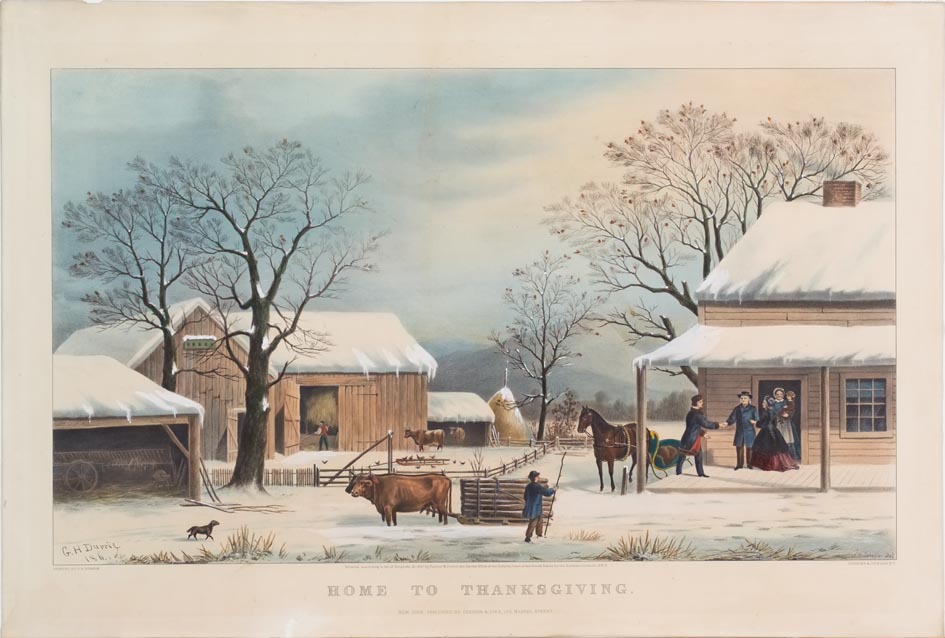

“Home to Thanksgiving” (1867)

“Home to Thanksgiving” (1867) (15’’x25’’) (hand colored lithograph) is from the Currier and Ives company. The original painting was by George H Durrie (1820-1863) of New Haven Connecticut. Currier and Ives promoted Durrie’s paintings in several prints. The last Durrie print was “Home for Thanksgiving,” and it continues to be popular today. The scene is a winter day with snow on the ground. In the middle ground, a young man has just arrived home in a horse-drawn sleigh and greets his family gathered on the front porch of the house. In the foreground is a dog and a skid of logs pulled by oxen. The young man with the skid raises a stick in greeting. A barn full of hay, cows, and chickens, and a silo complete the winter scene. The modest farm is well-kept. The celebration of Thanksgiving is about to begin.

“A Pilgrims Grace” (1897)

“A Pilgrims Grace” (1897) (16’’x20’’) was painted by Henry Mosler (1841-1920). He was born into a Jewish family in Prussia. When Henry was eight years old, his family immigrated to America and settled in Cincinnati. He was trained as an artist in Paris and Dusseldorf. Exhibitions of his work in the Paris Salon were successful. As popular as Thanksgiving is as an American celebration, few painters attempted to depict the original Thanksgiving. When they did so, the colonists out-numbered the native Americans, and appeared to be the hosts.

Mosler, popular for his American genre paintings, chose to depict a family at prayer over a meager meal. Dressed in Pilgrim black and white, the family is safe inside the log cabin. A fire burns in the fireplace, and the black and white cat curls up on the steps.

At the conclusion of the American Revolution, President Washington called for “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer” for the successful conclusion of the war. As President, Abraham Lincoln designated the last Thursday of November as “a day of Thanksgiving.” On October 17, 1863, Harper’s Weekly published Lincoln’s proclamation.

“Giving Thanks” (1942)

“Giving Thanks” (1942) (11’’x14’’) was painted by Horace Pippin (1888-1946). He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania. While he was in school, he entered a contest and won his first art supplies, a box of watercolors and a set of crayons. Famous for his American genre scenes, Pippin also painted landscapes, scenes from American history, including scenes of slavery. “Giving Thanks” is not a specific reference to Thanksgiving; however, it depicts the family seated at a simple wood table in a log cabin and offering thanks for a meal they will share together. The setting is simple. The sentiment is sincere.

Pippin enlisted in the first World War and became a member of K Company, a largely black regiments known as the Harlem Hellfighters. They were awarded the French Crois de Guerre. He began making art in his 20s, and throughout his career he returned to images of his time at the front. Pippin was discovered in 1941 by the art dealer Edith Halpern, and his career bloomed. His work is in the collections of America’s prestigious museums. Writing about a memorial exhibition of Pippin’s work, art critic Alain Locke described Pippin as “a real and rare genius, combining folk quality with artistic maturity so uniquely as almost to defy classification.”

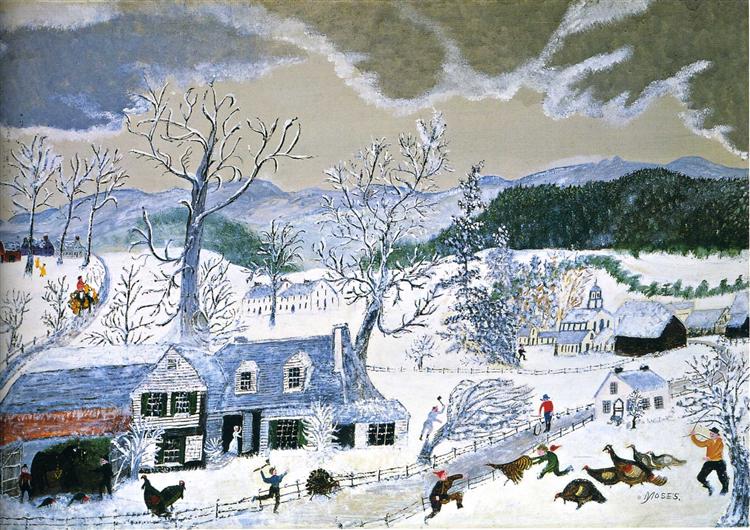

“Catching the Turkey” (1943)

Grandma Moses began painting in her 60s. Her paintings of rural life in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries became extremely popular after 1939. One of her favorite subjects was the farm family preparing for Thanksgiving. “Catching the Turkey’’ (1943) depicts the annual event. In this winter scene, a large farm house sits by a road leading into town. A school house, church, and other town building can be seen at both ends of the road. In the yard, a man is busy chopping firewood. The real action is at the front of the painting. One boy wields a hatchet, another throws a snowball, and a third boy vigorously grabs a turkey’s feathers. There will be no lack of turkey for dinner this year.

The turkey was described by Benjamin Franklin as “a much more respectable bird…a true original native of America.” He considered the eagle “a rank coward.” Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson were among those assigned to pick the American emblem, but Franklin did not make his thoughts about turkeys and eagles public. In a letter to his daughter, Sarah, on January 26, 1784, Franklin wrote about the virtues of the turkey. The story began to be circulated in the newspapers. Franklin never proposed the turkey as the national symbol.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Darrell Parsons says

Thank you! I like seeing the art works, and reading about them in the historical context.