Our Lady of Guadalupe is the Patroness of the Americas. The celebration of her feast day on December 12 dates back to the 16th century. Her story can be found in several chronicles of the time. She is particularly important in Mexico, where her story originated.

Cape with image of “Virgin of Guadalupe” (1531)

On Saturday morning December 9, 1531, on Tepeyac Hill, 28 miles from Mexico City, the Virgin Mary appeared to Juan Diego, a 57-year-old widower of Aztec ancestry. She spoke in Nahuatl, his native tongue. She told Diago to ask the bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumarraga, to build a chapel in her honor on the place where they stood. He told the bishop of his vision, and the bishop asked for a sign from the Virgin. She appeared again to Diego and told him to gather roses, even though it was winter. He gathered the roses in his cloak (tilma) and returned with them to the bishop. When the roses tumbled from his cloak, the image of the Virgin miraculously appeared on the garment. The ‘’Image of Virgin of Guadalupe” (1531) on the cloak hangs today above the high altar of the new Basilica of Guadalupe on Tepeyac Hill. The cloak was a catalyst for the conversion of many indigenous people to Catholicism. She is the patroness of the Americas and a symbol of Mexican identity. The Basilica is one of the most visited Marian sites in the world, and the most visited Catholic church except for St Peter’s in Rome.

The crown above the cloak was placed there on October 12, 1895, during the Canonical Coronation of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The Mexican flag hangs below the cloak.

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1691)

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1691) (72”x49’’) (Los Angeles County Museum) was painted by Manuel de Arellano (1662-1722), a well-known artist in 17th Century Mexico. The many paintings of the Virgin of Guadalupe were intentional copies of the painting on the cloak. As a result, the image was not altered from the original, but in almost all, four scenes of Juan’s interaction with the Virgin were added to the four corners. Later artists also added elaborate borders of flowers, particularly roses, and birds. Arellano painted in the Spanish Baroque style of chiaroscuro, using a rich color palette in the border.

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1691) (detail)

In the fourth and final part of the story, Diego holds his cloak with the roses, and kneels in the presence of the Virgin. Mexico City can be seen beneath her image, and the image of the Virgin can be seen on the edge of the cloak.

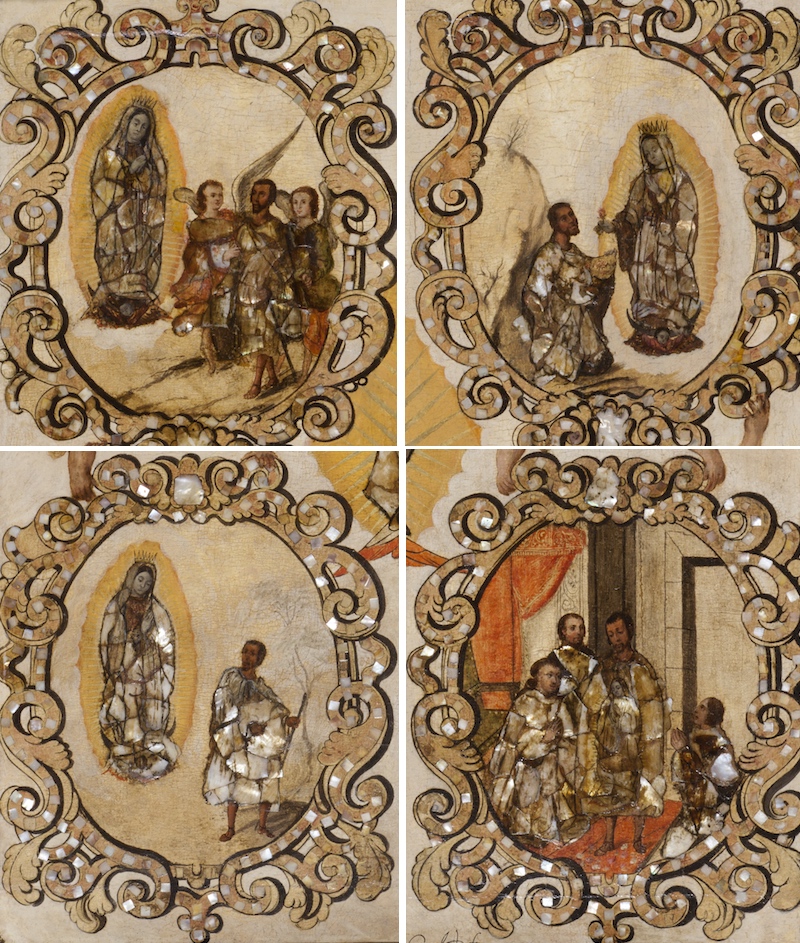

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1698)

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1698) (84”x37’’) was created by Miguel Gonzales. The medium is mother-of-pearl on wood, called enconchado, popular at the time. A variety of shells are placed on the painting like mosaic tiles and then covered with a glaze. Gonzales’s work repeats the traditional images, but the medium makes the work glow.

Angels hold the four corner scenes, a dove flies above Mary’s head, a unique shield sits at the Virgin’s feet, all surrounded by an elaborate floral border that includes red and gold flowers and small scenes of a ladder, palm tree, ship, lily, and fountain from Bible references. For example, Mary was believed to be the ship of salvation, as was Noah’s ark. The white lily is a symbol of Mary’s virginity. Marion iconography was abundant in Baroque paintings.

“Virgin of Guadelupe” (1698) (detail)

At the top left corner, angels guide Diego to the Virgin. At the top right, Mary appears to Diego. At the lower left, Diego goes away with a cloak full of roses. At the lower right, Diego shows the roses and the image on his cloak to the bishop.

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1698) (detail)

The shield beneath the figure of the Virgin had both religious and political significance. The creoles of Mexico sought a symbol that would distinguish them from old Spain. The eagle and cactus became popular. Mexican myths told about the founding of the ancient Aztec capital city Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. The solar god Huitzilopochtli told the people they would find the destination of their new home when they found an eagle on a cactus. The current Mexican flag design was adopted on September 16, 1968, but the central image is a version of the original 1821 design, and it also is found in Gonzales’s shell inlay work. Famous explorer and conquistador Hernando Cortez (1485-1547) carried a banner with the image of the Virgin when he brought down the Aztec empire in 1521.

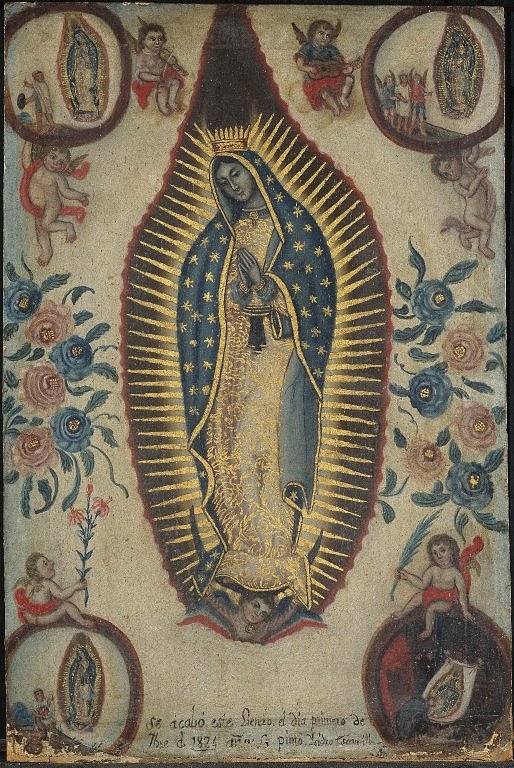

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1824)

“Virgin of Guadalupe” (1824) (23’’x15’’) was painted by Isidro Escamilla after the 1821 Act of Independence that formally ended Spanish reign in America. Always a popular image, the Virgin of Guadalupe became even more important as a figure whose divine help was a factor in freeing the people from Spanish rule. The part in Mary’s hair is a symbol of her virginity. She wears a cross, her hands are folded in prayer, and she wears a dark ribbon around her waist, over her womb. She is expecting a child. The Spanish word for pregnancy, encinta, means adorned with a ribbon. Her blue-green cloak represents Heaven; the reddish robe represents Earth. The stars on her robe are arranged in their position in the sky on December 12, 1531.

Her reddish gown is decorated with four-petaled jasmine flowers, a sign of the divine to the Aztecs and a symbol that the age of peace has come. A jasmine flower is placed over Mary’s womb. Mary is surrounded by the rays of the Sun. The crescent Moon under her feet is a Christian symbol of her perpetual virginity as well as of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent of the Moon. An angel supports both the Moon and the Virgin. At the bottom, the two angels hold a rose and a palm branch, and at the top, one plays a violin while the other plays a guitar. Red and blue roses adorn the sides. Escamilla used gold paint to depict the rays of the sun, to cover Mary’s gown with jasmine flowers, and to accent the roses. Her crown also is gold.

The Virgin of Guadalupe who appeared to Diego was Aztec; therefore, her complexion was traditionally painted with a greyish tint. Her connection with Aztec culture and Roman Catholicism continues to be strong. Twenty-five popes have honored her, and Pope John Paul II visited her shrine four times. On his third visit in 1999, he declared December 12 the Liturgical Holy Day for the whole continent. Juan Diego was canonized by John Paul II on July 31, 2002.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.