America sculpture after the Revolution of 1776 was for the most part folk art and ship figureheads carved in wood. The only stone sculptures were grave markers. By the Nineteenth Century, as the Country grew and prospered, Americans began to look for permanent statuary to commemorate important persons and events. American sculptors adopted the then popular European Neo-Classical style based on Greek Classical art (480 to 332 BCE). They went to Rome to learn the craft and create their sculptures because the famous Seravezza and Carrera marble quarries were located near there. The first marble bust by an American sculptor was “General Andrew Jackson” (1815), sculpt by William Rush.

Thomas Gibson Crawford, born in New York in 1814, was one of these successful early sculptors. As a child he showed an interest in art. In 1833 he entered the New York studio of John Frazee and Robert Launitz who were wood sculptors. His skill was such that he went to Rome in 1834, with a letter of introduction from Launitz to Danish sculptor Bertel Thorwalson (1770-1844), one of the most popular sculptors in Rome. Crawford became his student, and by the late 1830s, Crawford found patrons and began a successful career as a sculptor in marble.

The Neo-Classical style was evident in Crawford’s work “Orpheus and Cerberus” (1843) (67.5” x 36” x 54”) (2340 lbs.) (Seravezza marble). Crawford selected the story of Orpheus and Eurydice from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The figure of Orpheus is depicted according to the Classical Greek ideal for nude male heroes: perfectly proportioned, accurately muscled, and of an appropriate age. Orpheus carries the golden lyre given to him by the god Apollo, who also taught him to play and sing. Praised by all living things for the exceptional beauty and power of his music, Orpheus has lulled to sleep the ferocious three-headed dog Cerberus, guard at the gate of the Underworld.

Orpheus’s great love Eurydice had died and gone into the Underworld. The musical laments of Orpheus so affected the gods that they allowed him to bring her back from the Underworld. One condition was imposed: Orpheus could not look back at Eurydice as she followed him until they crossed the border. Fearing she had lost her way, he looked back. Eurydice immediately faded back into the Underworld, lost to Orpheus forever. The viewer cannot not sure whether Orpheus is entering the Underworld, as his face is thoughtful and determined, or is he leaving without his love. The concentrated look on Orpheus’s face is irrevocably linked to the Classical ideal. In order to succeed at any endeavor, the perfection of the body must be matched by the intelligence of a rational mind. Maintaining a clear and reasoning mind is imperative at all times and in all situations.

Nineteenth Century patrons sought a heroic story but one tinged with romance and above all steeped in sentiment. Crawford supplied both. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and George Washington Greene, American Counsel in Rome, were so taken by the sculpture that they organized the sale of subscriptions to Boston residents for the purchase of the statue. It was displayed in 1844 in a specially designed exhibition space at the Boston Atheneum. The statue was a major success in Boston, and Crawford’s career was launched.

Crawford’s great success was due to his skill with marble, but also for his ability to understand the sentimental nature of his patrons. Sculptures with the titles “Mexican Girl Dying” (1853), “Christian Pilgrim in Sight of Rome” (1847), and “Babes in the Wood” (1851), are examples of Crawford’s sentimental sculptures. “David Triumphant” (1845-48) (45”) (NGA), a subject much interpreted in art, is depicted as a very young and innocent boy with curly hair. He stands in a Classical Greek contrapposto pose with his right leg supporting his weight, his torso in an S-curve, with his left foot on the large head of Goliath. His right arm is cocked on his projecting hip, and his left arm is draped over a harp, that also supports his left side. He calmly looks down at the giant he has just killed. He wears a laurel wreath, symbol of victory in Greece. The title may be “David Triumphant,” but his face shows no such emotion. As was expected of a hero, he is quietly contemplating Goliath and what he has just done.

Thomas Crawford received three commissions from the United States Government for sculptures at the Capitol. He was commissioned in 1854 to design and sculpt a marble pediment for the east front of the Senate wing that he titled “Progress of American Civilization.” A second commission for a rectangular relief over the entrance door to the Senate chamber was titled “Justice and History.” The third commission came in1855, when the design for a cast-iron dome on the Capitol building was approved. The dome was design by Thomas Walters and it included a 16-foot-tall statue holding a liberty cap on a long rod with a slave touching it, depicting an ancient Roman ceremony bestowing freedom. Crawford created three full-sized plasters sculpture to be cast in bronze or carved in marble in the United States. Unfortunately, Crawford died unexpectedly at age forty-three in 1857. The full-scale models were shipped in pieces to America. The Capitol works were installed in 1863.

The themes of Crawford’s Capitol sculptures were symbolic of America’s ideals. “Freedom” (1863) (19 feet 2 inches) (23,96.82 pounds) was placed on the Capitol dome; a 35-gun salute was answered by return salutes from twelve forts in the Washington DC area. A discussion regarding the finished version of the statue was carried on between Captain Montgomery Meigs, the supervising engineer, and Crawford through the exchange of letters and photographs between Rome and Washington. Meigs wrote to Crawford “We have too many Washingtons, we have America in the pediment. Victories and Liberties are rather pagan emblems, but a Liberty I fear is the best we can get.”

Crawford responded with a photograph of a maquette (small model) that he titled “Freedom Triumphant – in Peace and War.” The female figure of Freedom wears a classical Greek peplos gown and on her head a wreath of wheat, symbol of American agriculture. She holds in her right hand a branch of laurel, symbol of victory in Greece when woven into a wreath. In her left hand she holds a sword and shield.

A second maquette depicted the female figure wearing a liberty cap; a soft cone shaped hat with the crown bent over, associated with the Greek Island of Scythia and worn by French Revolutionists. The hat is circled by stars and Liberty holds a sword in her right hand, and a shield and a laurel wreath in her left hand. Crawford titled this version “Armed Liberty.” It was rejected by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who did not approve of the Liberty Cap because it was a symbol of freed slaves. He stated “…its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and should not be enslaved.” He suggested a helmet circled with stars. Secretary of War (1853-57) under President Franklin Pierce. Jefferson Davis was elected President of Confederacy in 1861.

Crawford’s third figure wears a Roman helmet surrounded by nine stars. The symbolic meaning of the nine stars in unclear, but nine is a sacred number to the Free Masons, including George Washington. Crawford described the helmet as bearing a “crest of which is composed of an eagle’s head and an arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes.” “Freedom” wears the classical peplos gown that is closed in front by a brooch inscribed with the letters US. A Roman toga, decorated with a fringe of fur and ornamental balls, is draped over her shoulders. In her right hand she holds a sheathed sword tied with a fringed scarf. Her left hand supports the shield of the United States bearing stars and stripes, and also holds a victor’s laurel wreath. On the helmet and her shoulders are ten bronze points covered in platinum to protect her from lightning.

“Freedom” stands on a globe bearing the motto “E Pluribus Unum” (Out of Many, One). Beneath the globe are Roman fasces and laurel wreaths. Fasces were formed in ancient Greece and Rome by bundling wooden rods tightly around an axe, symbolic of the power achieved by many working together. The pedestal is 18-feet-tall and made of cast-iron. When “Freedom” was cast, some of the workers on the project were slaves. With the height of the dome at 288 feet, topped by the pedestal at 18-feet, the statue of “Freedom” rises high over the Capitol dome.

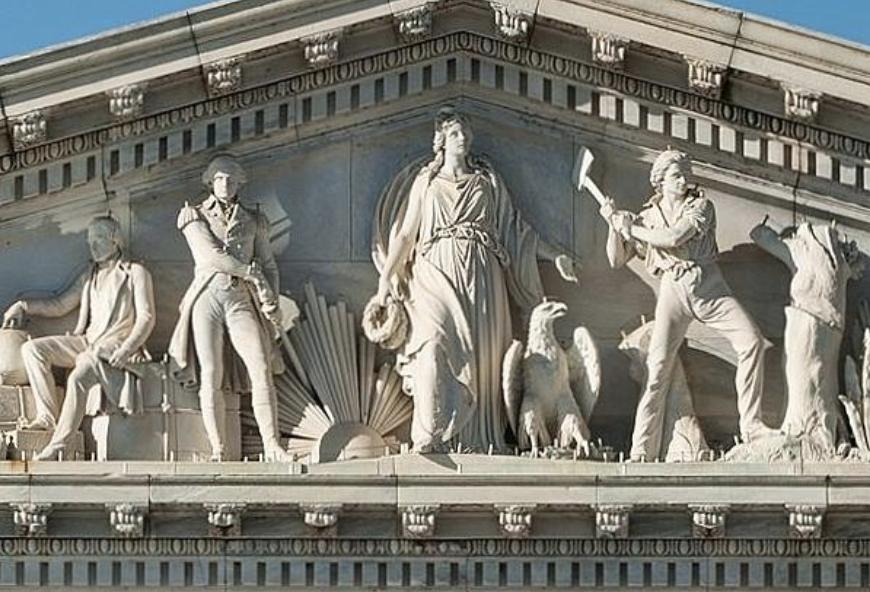

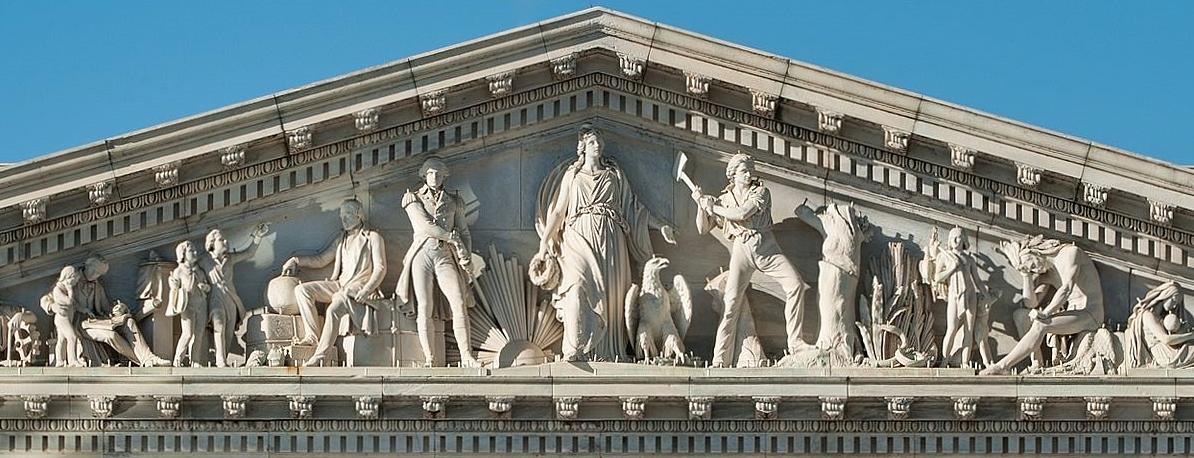

Crawford’s marble pediment sculpture “Progress of American Civilization” (1863) (60 feet x 12 feet), is located over the east entry door to the Senate wing of the Capitol. The central figure in the pediment is “America.” She wears a liberty cap and holds two laurel wreaths in her right hand. The sun rises behind her. In an unusual composition, the figures in the are composed to read from left to right instead of branching out to either side. Beginning at the point on the left is a mass of Earth representing the land. Next, an Indian mother cradles her child and faces the corner and the Earth. A seated Indian chief faces the center of the composition toward American progress. Crawford carved this figure as a single marble work in 1856 and titled it “The Indian, The Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization” (1856) (60” x 55” x 28”). Given the title, Crawford must have felt this work was appropriate for inclusion in the pediment.

The next figure is a hunter with game slung over his shoulder. The tradition of a triangular pediment requires each figure, except the larger central figure, to be in equal scale and in a position logical to the height of the space. The face of the hunter with the game is that of a mature male, but the height of the figures is that of a child. A pair small scale figures also appear on the opposite side of the pediment in the same location. As careful as Crawford was to the Neo-Classical style, these two exceptions seem to be the only lapse in skill witnessed in Crawford’s work. Alternatively, they might be a concession made by those who carved the pediment from Crawford’s design. Completing this side of the pediment, a woodsman is shown cutting down a tree and next to “America” is a bald eagle.

To the right of the figure of “America” a Revolutionary War soldier stands with his hand on his sword, ready to draw it to defend America. A seated merchant is next, followed by the two smaller scale male figures mentioned above. Facially the slightly taller figure who gestures skyward is older than the young boy carrying a book and looking up. Beyond them a full-scale seated school teacher holds an open book on his lap and instructs a young boy. At the point a working man reclines against a large gear and holds a hammer. At his feet are an anchor and sheaves of wheat, symbols of American progress on land and sea.

“Justice and History” (1863) (11’2”) was placed in 1863 over the Senate Chamber entrance. The two female images represent important American values, and were positioned presumably over the door to remind Senators of their duty every time they entered the chamber. Both figures are dressed in classical Greek attire to represent the idea of Democracy, first conceived and practiced in Athens Greece. Filling the long rectangular space, both women recline side-by-side on a long banqueting couch. Their legs are stretched out toward each end and their arms rest on a pillow/globe with a stars and bars design. “History” is a young woman with long flowing hair and wearing a laurel wreath. She holds a large scroll inscribed with the words HISTORY, JULY,1776. American was young, and “History” looks slightly to the right toward the future. “Justice” is a mature woman with her head covered and bound up in the style of a mature Greek woman. In her left hand she holds a large book inscribed with the words JUSTICE, LAW, ORDER. Her right arm leans on the pillow and her hand holds the top of the scales of justice. Due to the height of a set of scales, the chains holding the scales and the two pans are collapsed at the edge on the couch.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.