Portraits of President George Washington were the most requested paintings in America for decades. Although disinclined to do so, Washington, at the request of Martha, sat for Charles Wilson Peale at Mt. Vernon in 1772. Washington was a Colonel in the Virginia Regiment at that time. Over the years Peale did seven portraits of Washington. Gilbert Stuart painted two portraits of Washington in 1795 in Philadelphia. The success of his first portrait eventually generated 75 copies. Stuart’s painting became the model for Stuart’s later portraits and for other painters to fulfill the numerous requests that flowed in from individuals and states.

The first sculpture of George Washington was the result of the efforts of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, both in Paris after the American Revolution. In 1784, Benjamin Harrison V, the Governor of Virginia, contacted Jefferson, in Paris serving as the American Minister to France, to look for a good artist to sculpt Washington. Jefferson, a Francophile, knew of Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), an artist known for his sculpted portraits of notable French persons. Jefferson met Houdon and commissioned him to create a monumental equestrian statue for Virginia. Ultimately the commission became a standing figure.

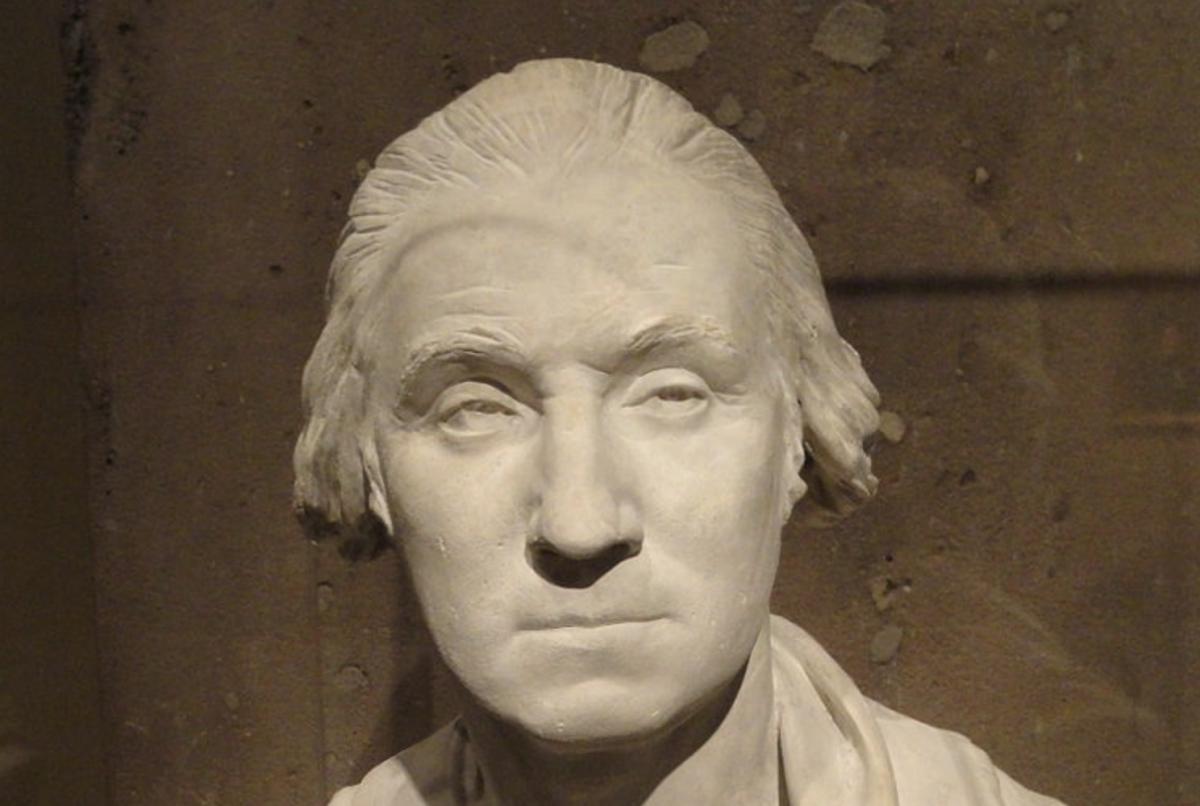

Coincidentally, Houdon had carved a bust of Benjamin Franklin in 1778. Considering the commission from Jefferson, Houdon was reluctant to carve a three-dimensional figure using only a drawing by Charles Wilson Peale. Franklin invited Houdon to come to America to meet and sculpt Washington. Jefferson, Franklin, and Houdon arrived at Mt Vernon in1785. Washington reluctantly agreed to sit for Houdon, but only for the time required for Houdon to make a wet clay bust in terra cotta. Washington also agreed to the making of a life plaster cast of his face. Houdon made a gift of the terra cotta to Washington, and it remains at Mt Vernon today. Houdon also took Washington’s measurements in order to produce the statue.

Washington insisted he appear dressed in contemporary clothing, not military garb. To this end, his right arm rests on a gentleman’s walking stick. He is posed in contrapposto, innovated Polykleitos of Athens (c450 BCE) to depict the human body in its most comfortable standing position. Washington’s body appears comfortable and relaxed, and his face appears calm but thoughtful.

Symbolically, Washington’s left arm rests on Roman fasces, wooden rods bound together to represent power in unity. In Rome the hand-held fasces was a weapon with an axe firmly fixed at the top. America adopted the ideal of democracy from the Athenian Greeks, and organization of the rule of law from the Romans. In the United States Capitol and elsewhere the fasces are displayed as a bundle of thirteen rods bound together as an iconic symbol of the United States of America. Washington’s sword hangs from the top of the fasces. On the right side is the walking stick of the public man, and on the left is the sword of the general. Critics often state that Houdon had captured both the private and the public Washington. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote, “Nothing in bronze or stone could be a more perfect image than this statue of the Living Washington.” Houdon’s statue has been duplicated many times, and copies can be found at Valley Forge, inside the Washington Monument, and in Philadelphia, to mention a few.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s birthday, the United States government commissioned the first American sculptor, Horatio Greenough (1805-1852), to create a sculpture of Washington for the Capitol Rotunda. Greenough, born in Boston, was a strict classicist at heart. Trained in Rome, he sculpted several portrait busts in Boston and Rome. He used the life mask of Washington made by Houdon as the model for Washington’s face. The seated figure of Washington made of Carrara marble weighed twelve tons. It is recorded that twenty-two yoked oxen were needed to move the statue from Florence to the port at Genoa. Along the way, Italians crowded the streets thinking it was the sculpture of a saint.

Greenough’s statue was on display in the Capitol Rotunda from 1841 to 1843. The statue was controversial from the start. Most surprising to many viewers was the well muscled, bare-chested figure, wearing a Roman toga and sandals, and seated on a throne. Greenough had modeled the statue on the ancient sculpture of Zeus in his temple at Olympus. Washington chose the title President rather than King, and for many this representation was not the Washington they expected or wanted. Carved on the front of the pedestal is the inscription “First in the Hearts of His Countrymen.” On the back of the pedestal Greenough carved an inscription in Latin: “Horatio Greenough made this image as a great example of freedom, which will not survive without freedom itself.” One of Greenough’s friends wrote, “This magnificent production of genius does not seem to be appreciated at its full value in this metropolis.”

Greenough fully utilized the classical ideal. Washington sits on a throne-like chair, with lion heads and paws forming the arms. The chair’s right side panel depicts Apollo, the Sun God, driving his chariot across the sky. Standing at the back of the seat is a small figure of an Indian representing the old world. On the panel at the left side of the chair, baby Hercules defeats the python, and above is the small figure of Christopher Columbus representing the new world. Washington’s right arm is raised over his head and his hand is posed in the Roman imperial gesture with one finger pointing to the heavens, meaning the subject was the one and only one in charge and ruled by the Gods’ assent. Washington’s left arm is raised and holds his sword, hilt toward the viewer: Washington won the war with the sword and had given America to the people.

In 1843, Greenough suggested the statue be moved to the east lawn of the Capitol. It remained outside for the next sixty years subject to the elements. It became part of the Smithsonian collection in 1964, was restored, and placed in the National Museum of American History. The photo of the statue in place on the Capitol grounds was taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864 to1957). Johnston was one of the first American women photographers to achieve prominence. Notable for her portraits of presidents and diplomats in Washington, DC, she was a photojournalist, writer and photographer of magazine articles, chronicler of southern architecture and gardens, and a world-traveled photographer who exhibited nationally and internationally.

Vinnie Ream was born in a log cabin in Madison, Wisconsin. She taught herself to play guitar, piano and harp, and she composed music and sang. At age twelve she attended the Academy at Christian College in Missouri where her talents were encouraged and expanded to include art. When her family moved to Washington, DC, in 1862, she worked in the United States Post Office. She also was apprenticed to sculptor Clark Mills. On seeing Abraham Lincoln, she wanted to do a portrait of him. Lincoln was extremely busy as the Civil War was raging, and he was reluctant to have anyone or anything distract him from the necessary work for the Country. When Ream’s sponsor told Lincoln she was “a poor girl from the West,” he agreed to half- hour sittings while he worked at his desk. Ream writes of the experience: “I was a mere slip of a child, weighing less than ninety pound and the contrast between the raw boned man and me was great…His favorite son Willie had just died and this had been the greatest personal loss in his life… I remember him…slouched down into a chair… deeply thoughtful…I think he was with his generals, appraising the horrible sacrifices brought upon his people and the nation.”

When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, the Government commissioned the then eighteen-year-old, Vinnie Ream to carve his statue. A major controversy ensued. Objections to Ream were obvious. She was a woman, she had little or no formal training, and she was too young and too pretty. Senator Jacob Howard stated, “…having in view her sex, I shall expect a complete failure in the execution of her work.” However, she had strong support from President Andrew Johnson, General Ulysses S. Grant, and 31 senators and 114 representatives. Ream, as all great sculptors had to do at the time, went to Italy to find the marble and to sculpt the statue. This led to another typical criticism when the artist was a woman – plagiarism. Clearly she could not have done the work, someone else made it and she took the credit. Her mentor Clark Mills had to write a letter stating that he did not make the statue.

In their choice of Ream, the choice was correct. Vinnie Ream sat quietly with Lincoln for hours during the War and after the death of his son. She probably knew Lincoln as well or better than any one. Ream wrote of her statue: “I think that history is particularly correct in writing Lincoln down as the man of sorrow. The one great, lasting, all-dominating impression that I have always carried of Lincoln has been that of unfathomable sorrow, and it was this that I tried to put into my statue…when he learned that I was poor he granted me the sittings for no other purpose than that I was a poor girl. Had I been the greatest sculptor in the world, I am sure that he would have refused at that time.” The Lincoln statue has always resided in Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.