Xu Bing grew up in Beijing in the People’s Republic of China. His parents both worked at Peking University. His father was head of the History Department, and his mother was a researcher in the Department of Library Science. Xu’s father taught him calligraphy and Chinese history; he spent hours with his mother reading in the library and painting. Under Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) his father was sent to the countryside for re-education. To remain in school Xu was required to make propaganda banners. Mao wrote that it was “very necessary for educated youths to go to the countryside and learn from poor and lower-middle-class peasants.” Xu was sent for re-education in 1975. He worked at hard manual labor, but he states he learned humility and found calm. His talent in calligraphy was recognized and he was highly recommended for admission in 1976 to the May Seventh College of Art in Beijing. Although he hoped for a career in painting, he was assigned to the department of printmaking. He graduated in 1987 with an MFA in printmaking.

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao modified the Chinese language for the purpose of propaganda. Xu’s interest in languages and calligraphy, the propaganda banners he made, and the language changes he observed, inform a major part of his art. “It allowed me to see the changes in the Chinese language and the style of Chinese characters. At that point, I realized the style of these characters actually contained deep political messages.”

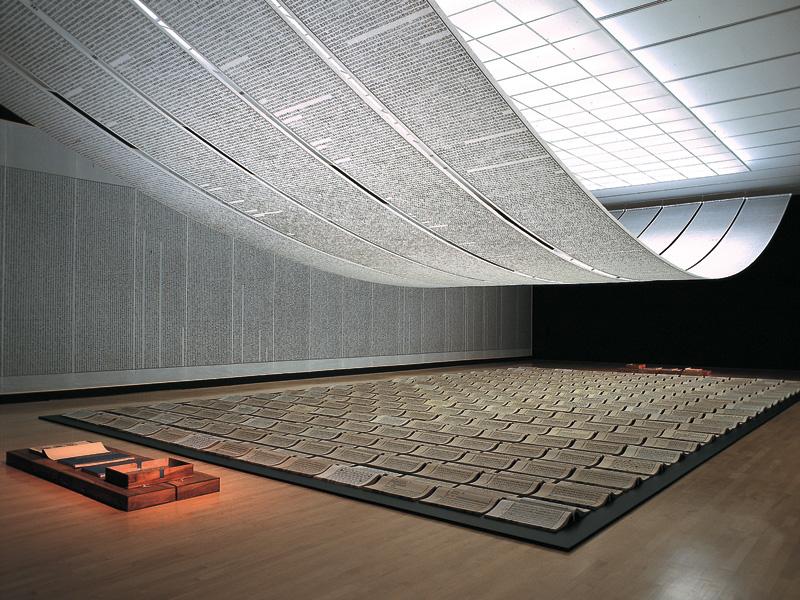

“Book from the Sky” (1987-1991) is an installation of four hand printed books and of scrolls printed with wood letterpress type that covers the floor, ceiling and walls of the exhibition space. Xu invented the 4000 glyphs and pseudo-characters that appear to be traditional Chinese characters, but they are not. He expanded “Book from the Sky” over the years from 1987 until 1991, and it has varied dimensions depending on its size location. After Mao modified the Chinese language, Xu’s use of his characters and text question the meaning of language. The work is complex and confusing but somehow familiar. In Chinese the title is “Fenxi Shijie de Shu” (A book that analyses the world). As in English, it is read from left to right and top to bottom. This work was not shown again in China for twenty years.

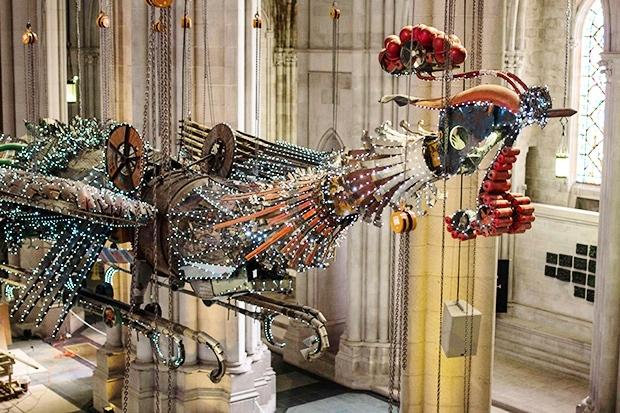

In 2008, Xu was commissioned by Lee Shau-kee, a Hong Kong real estate tycoon, and Cesar Pelli, the building designer, to create a magnificent sculpture to be placed in the atrium of the World Finance Center (Fortune Towers) which was being constructed in Beijing. They asked for a large crystalline phoenix. Xu’s first reaction when visiting the site: “It was impossible to image that with all the modern technology today, the building was constructed with such low-tech methods.” Most of the workers were migrant laborers who lived in nearby housing provided for them. He was appalled that workers living in squalor were building luxury towers. It “made your skin quiver.” Xu essentially refused to make the glittery sculpture he knew they expected; instead he created “Phoenix Project” (2008-2010) using recycled construction materials. Xu encouraged the constructions workers to gather debris from the building site and from several other construction sites in urban China. His choice of construction debris was intended to call attention to contemporary issues “including the rapid industrialization of the rural geography, and increasingly throwaway culture, and a lack of value for manual laborers.”

The phoenix is a significant, ancient Chinese symbol and Xu’s work displays a pair of phoenix with respect to historical representation of phoenixes that are often shown as a pair. The sculpted male, Feng, is 90 feet long. The female, Huang, is 100 feet long. Their combined weight is 120 tons and they hang 20 feet in the air. Junjii Jiang in an article published for Harvard University Press provides a specific description of the work. “Xu Bing translated the organic components of the bird into industrial ones, and while reinventing the bird’s design, he followed carefully the logic of each part. The hardhats form the comb because they are red and worn on top. The concrete mixer is the stomach because the two share a function of stirring and blending. The heads of both the male feng and the female huang are made from the nose of industrial jackhammers, a contemporary translation of their strength and ferocity (historical images of the phoenix often show the powerful bird with a snake in its talons or beak). The shovels apparently make good claws. A spade becomes a piece of feather because the handle’s function resembles that of the quill. The impellers are on the long tail feathers due to their relation to aerodynamics. Thus the phoenixes are by no means a haphazard assemblage of used materials; rather, the design is careful and thoughtful, and the logic of assemblage follows the anatomical structure of a bird and makes the piece a well integrated whole.” The phoenix sculptures are strung with thousand of lights to illuminate the works at night.

The phoenix first appeared in 2600 B.C.E. under Emperor Hung, and it is one of four mythical celestial beings. The Phoenix is immortal. At the end of its life it burns; like the fire it is both generative and destructive. It sacrifices itself for a significant purpose, and then is resurrected. Phoenixes are found in several ancient religions from Egypt to Rome, and from Mesopotamia to India. Phoenixes were found in the Garden of Eden, and Christianity they represent the resurrection of Christ. Not to forget Fawkes in Harry Potter. In each case they are beneficent forces representing resurrection.

The sculpture was interpreted correctly as critical of the Communist Chinese government and was disparaged in the press. The commissioners agreed to accept the work if Xu beautified it. Xu refused. Therefore the ownership of the work was in doubt until Barry Lam, a billionaire art patron in Taiwan, purchased it. The “Phoenix Project “ has traveled from the Shanghai World Expo (2010), to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (2013), to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City (2014), and to the Venice Biennale (2015), where they were suspended over the Grand Canal.

Xu Bing’s “Phoenix Project” was a departure from the use of text by the artist. The “Tobacco Project” was another such departure. He accepted an invitation to lecture and serve as artist-in-residence at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Durham, known as “tobacco town”, is also the home of the Duke Medical Center, a major research center for cancer. As a result of his father’s death after a long struggle with lung cancer of lung cancer, Xu researched the history, cultivation, culture clashes, trade routes, manufacture, and medical aspects of tobacco use. He turned tobacco and cigarettes into works of art. The first exhibition was in Durham (2000), the second in Shanghai (2004) and the third in Richmond, Virginia (2011). After a two week residency in Richmond, the resulting exhibition included several of his earlier tobacco related works and culminated with a piece composed of 500,000 cigarettes, some standing on the tip and others on the filter. Following Xu’s template, a group of students produced a dazzling and massive tiger skin rug. Xu’s Chinese heritage meets modern Chinese culture; tiger skin rugs are a major status symbol in China.After leaving China in 1990, with several other contemporary artists in reaction to the Communist crack down due to Tiananmen Square demonstration (1989), Xu moved to the United States, at the invitation of University of Wisconsin, Madison. He lived there and later in New York City producing work and lecturing internationally. In 2008, Xu Bing was invited to return to China to serve as the Vice President of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, the former May Seventh College of Art in Beijing. He was appointed President of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2014. Xu continues to create art, to teach and lecture internationally. Xu Bing is considered to be one of China’s foremost contemporary artists

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.