A Renaissance person is described as someone with many talents and areas of knowledge. Cambridge resident, David Stevens, is such a man, coming to Cambridge from Easton in 2018 after living there and raising his family there for almost 30 years. But that was just the latest of many moves around the country, learning and practicing many different creative pursuits.

Originally from Kalamazoo, MI, David says that he has been an artist all his life. In his bio, Stevens says, “The University of Michigan opened my eyes to the world of art and self-expression. Upon graduating in 1970, I felt driven to pursue life as an artist.” After driving a cab while painting and drawing over a period of eight months, Stevens moved to Los Angeles. “California seemed to be the place to be at the time.” There he worked in a small shop in Santa Monica and learned to work in stained glass. After a year at the studio, he opened his own stained glass studio, and worked there for eight years.

According to the Stained Glass Association of America, the social changes of the 1960s created an environment for stained glass to move from the religious to the secular world as building of churches slowed. “Hippies” spread “eastward from San Francisco…rehabbing the old houses, painting them bright colors and…repairing the stained glass.”

The ’60s also saw developments such as small furnaces for hot glass make the art accessible to individual artists instead of only in large studios that had been previously required. This did away with the requirement of apprenticing to learn the art, and hot glass began moving into college curricula.

Stevens’ largest stained glass work consisted of panels commissioned from by him by a school in Baltimore, using a 1% fund set aside for the arts. The 15 panels, arrayed together, each 30 foot tall by 5 feet wide, depicted Eastern Shore scenes moving from the water onto the land, showing native birds, animals and plants. The entire piece took almost a year to make. Sadly, the school has since been torn down and Stevens does not know what became of the panels.

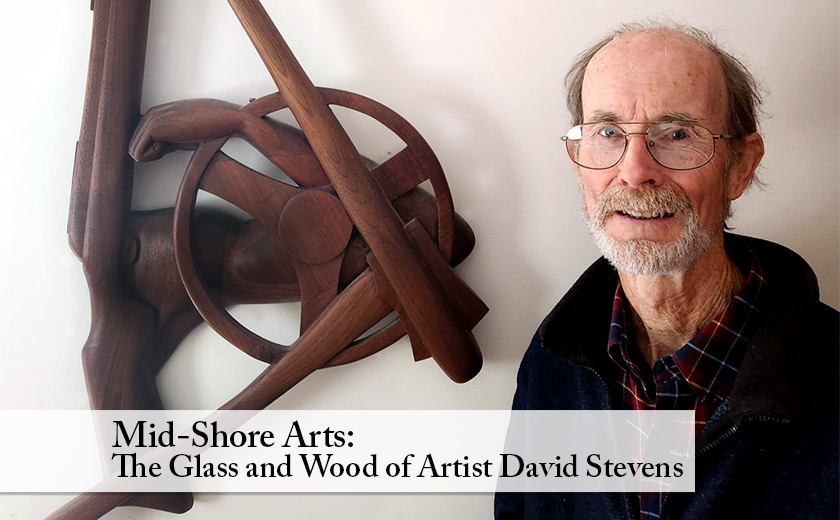

While in California, having pushed stained glass as far as he was interested, Stevens also took up wood working, which he practices to this day in his home studio. For some time, he melded his skills and talent in stained glass with his knowledge of woodworking to create artwork of bright glass and smooth sinuous wood. “Working with my hands in stained glass and wood comes very naturally to me,” he says. “Coming up with a design and then making it work” is easy and enjoyable. But “the rigidity of the design demands of using wood and glass together lead me to pursue wood alone in the mid 1980s.”

Choosing to make his living as an artist, he found the best way to make a living with his art was through photography, mostly black and white, and worked out of his own darkroom. The advent of digital cameras and phones, however, definitely dampened the market for photographs. Closer to home, he has shown his work in River Arts in Chestertown, the Maryland Federal of Art in Annapolis and Main Street Gallery in Cambridge.

“The thing about art,” he says, “you are not going to make a lot of money. As long as I can just get by that’s enough. It’s also good to be healthy.”

More recently, Stevens created a container measuring 76 inches x 20 inches and ¾ inches wide, filled it with water and started taking pictures of the results of dropping ink into the water, photographing the progress of the process. He notes that he loves the translucence of the ink as it flows into the water, how the ink creates “thin intricate threads of color in the water.” The effect is something like watching clouds, how they melt and slide, and, if you’re so inclined, the results I saw call forth dragons and other such whimsies in the mind’s eye and its need to see “something” even in the most abstract creations.

More recently, Stevens created a container measuring 76 inches x 20 inches and ¾ inches wide, filled it with water and started taking pictures of the results of dropping ink into the water, photographing the progress of the process. He notes that he loves the translucence of the ink as it flows into the water, how the ink creates “thin intricate threads of color in the water.” The effect is something like watching clouds, how they melt and slide, and, if you’re so inclined, the results I saw call forth dragons and other such whimsies in the mind’s eye and its need to see “something” even in the most abstract creations.

As a logical extension and follow-up to working with these successfully unplanned art configurations of letting what happens happen, Stevens has moved into using watercolor paints in much the same way he has used the ink in the water container, dropping water color onto wet paper and allowing it to move however it will. “I photograph each step – sometimes the first few steps are the best for a piece that’s totally abstract. It is good to have a record of the steps because sometimes I push the medium to the point of too much.”

When asked how he would explain his art, he says, “the art pretty much explains itself,” and references his website, horizonphotograph.com, as a good place to see the history of his work. He also shows his work on the walls of the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Easton (UUFE). UUFE also hosts other of its members’ art work, turning over the offerings once every month or so to keep it fresh and interesting.

These days Stevens says that he makes his art “just for me.” He says that he is retired from the career of art paying his way and now just enjoying the process and the joy of living with the results.

Tammy Vitale. an artist herself, has fallen in love with all the facets of art available in Cambridge/Dorchester County, and wants the rest of the world to get to know and love the arts and artists of this area as much as she does. Cambridge artists (broadly defined) are invited to contact her [email protected], subject line “Arts.”

David Stevens says

Thanks to Tammy

2 small typos on sizes. The 15 panels for the Baltimore project were 30 inches by 5 feet.And the container for holding water to photograph ink was 16 inches by 20 inches.

Nanette M Turanski says

It’s beautiful work. Love the wood sculpture of the musical instraments.