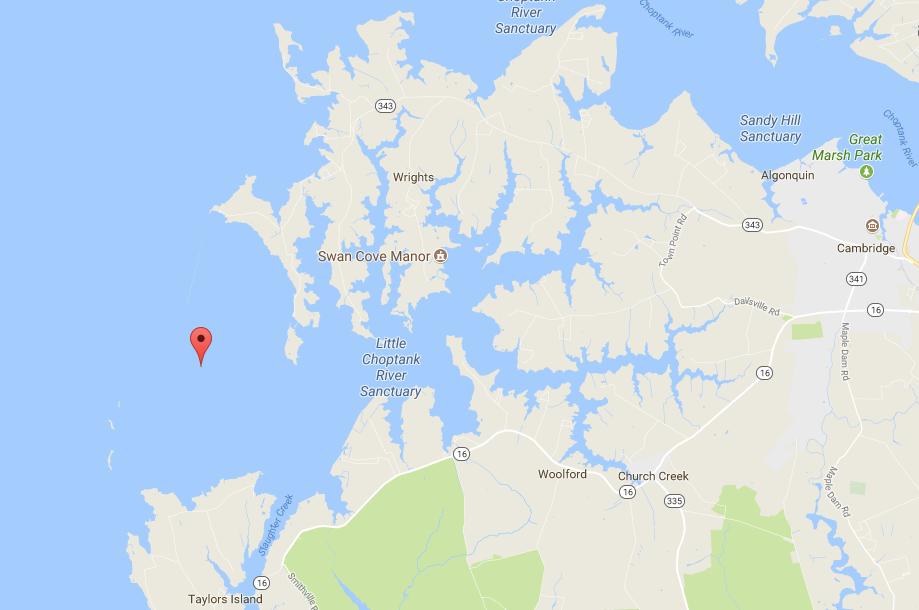

The state of Maryland has decided to reduce the large-scale oyster restoration project goal in the Little Choptank River after boaters ran aground at another sanctuary and some of the man-made reefs there had to be rebuilt.

The sanctuaries are among five planned to be built as part of a federal-state agreement to improve water quality in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

The project, which grows and plants oysters on man-made beds in protected waterways, has been touted by environmentalists and generally opposed by watermen. Numerous agencies have agreed to a longterm goal of growing oysters on at least 50 percent of restorable oyster habitat.

The project, which grows and plants oysters on man-made beds in protected waterways, has been touted by environmentalists and generally opposed by watermen. Numerous agencies have agreed to a longterm goal of growing oysters on at least 50 percent of restorable oyster habitat.

The habitat goal for the Little Choptank River sanctuary has been cut by 118 acres — about one-fourth of the original target.

This means there will be roughly 19.5 million fewer oysters at this site alone — enough to filter up to 1.03 billion liters of water per day.

Oysters’ capacity to filter water can vary widely depending on temperature, salinity and other factors, according to Matthew Gray, an assistant professor specializing in oyster feeding habits at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

A construction error in Harris Creek — Maryland’s first large-scale oyster restoration site — caused damage to multiple boats, as vessels grounded or scraped against stone-based reefs that did not meet five feet of navigational clearance, officials said.

Skeptical of oyster restoration from the start, watermen have complained of trotlines getting stuck in new stone river bottoms and boats being damaged by oyster reef “high spots” in Harris Creek. A trotline is a long, heavy fishing line with short, baited lines suspended from it. They are often used to catch blue crabs in Maryland.

Watermen depend on their boats to earn a living. No boat means no fishing. No fishing means no income.

The extent of damage to boats as a result of Harris Creek groundings varied widely, said Jeff Harris, a Tilghman Island waterman. Even a relatively insignificant repair requires taking the boat out of the water.

“You could lose maybe three days of work,” he said.

The state’s natural resources agency cited navigational risks for boaters and the inconvenience to trotlining in its decision to curb construction in shallower spots in its second oyster sanctuary — the Little Choptank — going forward, according to Chris Judy, Maryland Department of Natural Resources shellfish division director.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District was tasked with designing the reefs in Harris Creek and hired contractor Argo Systems LLC, based in Hanover, Maryland, to build them.

But after stone-reef construction in Harris Creek in 2015, the location was left with “high spots,” according to Angie Sowers, oyster restoration study manager at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Baltimore District.

Argo Systems could not be reached after repeated requests for comment.

The “high spots” in Harris Creek have since been leveled to meet specifications determined by the oyster recovery partners — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the Army Corps and the Oyster Recovery Partnership.

But for the Little Choptank, 118 fewer acres may have greater implications.

The oyster recovery partners finished planting 350 acres in Harris Creek in 2015, and it has been touted as the largest oyster restoration in the world. The Little Choptank project was scheduled to overtake Harris Creek, with 440 acres of river bottom to be covered with restored reef by late 2018.

In 2009, then-President Barack Obama signed the The Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration Executive Order, setting a goal of restoring 20 tributaries by 2025.

The goal was amended by the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement, which set out to restore oyster populations in 10 tributaries — five in Maryland and five in Virginia — by 2025, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Under the amended agreement, the oyster restoration partners agreed to restore 50 to 100 percent of “currently restorable oyster habitat” in each tributary, according to a 2011 Oyster Metrics Workgroup report. Restorable habitat has hard riverbottom, suitable for man-made reefs, which keep the bivalves from sinking into sediment and dying.

“In order to qualify as successfully restored,” said Stephanie Westby, oyster coordinator at NOAA’s Chesapeake Bay Office, at least 50 percent of the tributary’s suitable habitat must be restored.

The Little Choptank had 685 restorable acres at the project’s onset, Judy said. The original goal was to restore 64 percent of that restorable habitat — a total of 440 acres. Now Maryland has pared back the target.

Though the state is removing the shallower areas from the Little Choptank’s restoration plan, Judy said, “there is a commitment to make sure it’s 50 percent and we will do that.”

The Little Choptank’s new, 50-percent target is 342.5 acres.

“We’re disappointed,” Allison Colden, fisheries scientist at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, told the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service. “The state is doing the bare minimum to meet restoration standards and setting a bad precedent for future oyster restoration in Maryland.”

Judy maintained that the state’s only obligation is to restore at least 50 percent and that the department will do that.

At the new 342.5-acre target, 390 million fewer spat — baby oysters — will be planted in the Little Choptank.

The mortality rate of spat developed at the state’s Horn Point Hatchery is regularly 90 percent or higher once they are released into river, Judy said. The spat are highly vulnerable because of their small size, he added.

At a 95 percent mortality rate, 390 million spat translates to 19.5 million adult oysters.

No more stone

The amended version of the Little Choptank restoration also aims to avoid using stone and other substrate foundations for reef construction, a practice the watermen community has opposed from the project’s inception.

Robert Brown, president of the Maryland Watermen’s Association, said NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “didn’t do their job. They had criteria they were supposed to go about.”

“They put so many stones in there that it has disturbed the places where (watermen) crabbed at,” Brown said. “When you’re running a trotline down … you have a long line with bait on it and it’ll get hung underneath the stones and your line can’t come up.”

Harris, who took a 15-minute break from working on the water to speak with Capital News Service Oct. 20, said the oyster recovery partners “ruined Harris Creek for trotlining.”

He also pointed out that the lines actually shift with the tides, increasing the likelihood of the baited-lines getting snagged.

Brown added: “I don’t wanna see ‘em use no more stone, anywhere.”

The decision to avoid stone and substrate-based reefs raises concerns about the filtering potential of the oyster restoration.

Stone-based oyster reefs in Harris Creek produced an oyster density about four times greater per square meter than mixed-shell based reefs, according to NOAA’s 2016 Oyster Reef Monitoring Report.

“If you’re constructing reefs … for the oysters’ sake, then that points to the stone being a very promising material,” Westby said.

She added: “the science we have indicates” that oysters seem to do better on stone.

Constructing the remaining reefs exclusively from shell magnifies the shortage of recycled shell.

Shell is acquired from restaurants, which can recycle oyster and clam shells, or by purchasing out-of-state shells.

The Department of Natural Resources is also seeking a permit to dredge buried oyster shells from waterways, Judy said. “Every possible option is being pursued, whether it’s in-state or out-of-state.”

As it stands, the Little Choptank is approximately 63 acres shy of reaching the new 342.5-acre goal, Judy said.

In other words, the oyster recovery partners have completed more than 80 percent of that project with various reef-bases, including stone and substrate. The remainder will be built with a shell base.

In-the-water work in the Little Choptank began in 2014 and is expected to be completed mid-summer 2018. But that may take up to a year longer than expected “because you have to accumulate the shell to complete the project,” Judy said.

By Alex Mann

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.