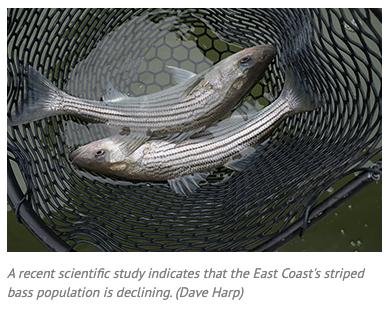

Prompted by a scientific finding that the East Coast’s most prized finfish are in trouble, Maryland, Virginia and the Potomac River are all moving to adopt new catch restrictions aimed at stemming the species’ decline.

Prompted by a scientific finding that the East Coast’s most prized finfish are in trouble, Maryland, Virginia and the Potomac River are all moving to adopt new catch restrictions aimed at stemming the species’ decline.

But many anglers are complaining about the complexity, fairness and even the adequacy of the cutbacks under consideration, which range from a quota tuck of less than 2% for commercial fishermen in Maryland to a 24% reduction in fish removed by recreational anglers in Virginia.

The two states are taking somewhat different tacks to comply with a directive from the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which regulates fishing for migratory species from Maine to Florida. Last October, the interstate panel ordered an 18% decrease in mortality of striped bass coastwide, including in the Chesapeake Bay, which serves as the main spawning ground and nursery for the species.

Striped bass aren’t in as bad a shape as they were in the 1980s, when Maryland imposed a total fishing moratorium on them for nearly six years. But scientists have warned that after rebounding from that earlier swoon, the number of spawning-age female fish has fallen once more to a worrisome level, and the species is again being overfished.

The interstate commission decided that commercial and recreational fisheries should share equally in the cutbacks it ordered. But it agreed to consider letting states curtail the two sectors by differing amounts, as long as the net effect achieves a “conservation equivalency.”

The commission meets again in early February to review and decide whether to approve the alternative approaches states have come up with.

All of the Bay jurisdictions are looking to throttle back recreational fishing pressure on striped bass because it’s considered the chief culprit in the population decline. Regulators are weighing a variety of combinations of rules that would shorten the fishing season or restrict the size and number of fish that can be caught. Maryland is also proposing to clamp down on the widespread practice of catch-and-release fishing when it’s otherwise not legal to keep striped bass.

The Potomac River Fisheries Commission recently posted the options it was considering, so anglers on the Bay’s second largest tributary will have a chance to comment at a Feb. 19 meeting of the bi-state commission’s finfish advisory committee. But the plans already aired for Maryland and Virginia waters have drawn the ire of anglers in both states. One oft-heard objection is over the recreational catch being cut more than the commercial harvest.

In Maryland and in the Potomac River, regulators have proposed trimming the commercial harvest by just 1.8%, while the recreational catch is targeted for a cutback of 20.6% below what was caught in 2017. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission, meanwhile, voted last year to reduce the commercial catch in the Bay by nearly 8%, while going for a 24% overall reduction in recreational losses in both the ocean and the Bay.

“Effectively, this will be transferring fish from the recreational sector to the commercial sector,” complained Tom Powers, a Poquoson-based angler. The Virginia Saltwater Sportfishing Association flooded the state commission’s email inboxes with more than 300 messages from its members, lobbying for equity.

But fisheries scientists say it’s recreational rather than commercial fishing that’s bringing striped bass down. Studies indicate that anglers catch many more striped bass, also known as rockfish, than commercial fishermen. Anglers kill still more when they release fish they’ve hooked that are too small to legally keep or are caught out of season. In 2017, more died after being released than were kept, scientists have estimated.

Alex Aspinwall, a data analyst with the VMRC, noted that the recreational harvest accounts for about three out of every five striped bass caught in Virginia waters. In Maryland, the breakdown is similar.

Bay jurisdiction regulators are loath to make deep cuts in the Chesapeake’s commercial striped bass fishery because it provides a livelihood for hundreds of people.

The Virginia commission did support a modest cut in that state’s commercial catch, extending by 11 days the period in the spring when larger fish are protected from being netted. The goal, Aspinwall said, was to improve the chances for big reproductive females to survive to spawn future generations of fish.

Cutting back on recreational fishing is trickier because regulators have to rely on what anglers want to tell them, rather than hard data. The hundreds of thousands of people who get recreational fishing licenses every year are not required to report their catch, as commercial fishermen are.

Some steps have been taken already to try to reduce the release mortality of striped bass. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources trimmed the minimum catchable size from 20 inches to 19 inches, reasoning that would result in fewer fish being thrown back and dying.

The state has also required the use of rounded “circle” hooks, which cut down on potentially lethal injuries to the fish’s mouth when caught. The Atlantic States commission has directed all East Coast states to mandate the use of circle hooks by 2021.

The VMRC, meanwhile, canceled its spring “trophy” season last year — a shutdown extended this year. Traditionally, for about four weeks in May and June, recreational anglers and charter boats have pursued the large striped bass that enter the Bay from the Atlantic to spawn. Virginia regulators said they shut down their trophy season to protect the big female fish, which produce the most eggs.

The VMRC, meanwhile, canceled its spring “trophy” season last year — a shutdown extended this year. Traditionally, for about four weeks in May and June, recreational anglers and charter boats have pursued the large striped bass that enter the Bay from the Atlantic to spawn. Virginia regulators said they shut down their trophy season to protect the big female fish, which produce the most eggs.

Maryland and the Potomac River, in comparison, are keeping their trophy seasons, though Maryland has cut its monthlong season nearly in half to match the two-week season in the Potomac.

Michael Luisi, the DNR’s director of fishery monitoring and assessment, defended keeping the season targeting the big spawners. The trophy fishery doesn’t take that many fish, he said, and it’s the only chance Maryland anglers have at the really large mature rockfish that anglers in other states can go after the rest of the year.

Virginia also adopted other conservation measures last year — adjusting catchable size limits, and most significantly, reducing the number of striped bass an angler could keep from two a day to one.

Some Virginia charter boat captains say the changes, imposed last fall, have caused bookings to dry up.

“I’m not going to pay $800 to go out on a boat and be only able to keep one of the fish I catch and it can only be 36 inches,” charter operator John Satterly said of his clients.

Regulators elsewhere in the Bay are weighing closing their striped bass fishery at different points of the year. In Maryland, they’re also looking to give charter fishing a break, even while restricting private anglers.

The Potomac River Fisheries Commission is eyeing four options, all focused on closing the striped bass fishery for varying lengths of time in the summer. That’s when fish are most stressed by high air and water temperatures and low dissolved oxygen levels in the water, noted Martin Gary, the commission’s executive secretary.

Depending on which option is chosen, Potomac anglers would not be allowed to keep any striped bass in most or all of July and August and possibly even later. They’d still be able to take two fish a day in the rest of the summer and in the fall.

Maryland’s DNR is considering a different set of options, which would close the summer striped bass season for shorter periods of two to three weeks in July or August. But it’s also looking at barring anglers from “targeting” striped bass during those closures, meaning that they could be cited for a fishing violation if spotted repeatedly catching and releasing the fish. That’s something no other Bay jurisdiction has proposed.

The DNR’s Luisi said that enforcing the “no targeting” rule could be challenging, because an angler can’t control what fish get hooked. But one fishing method that would be automatically suspect, at least in the spring, would be trolling, which involves towing multiple fishing lines through the water behind a boat.

“There’s nothing else in the Bay during March and April that people would be trolling up and down for,” he said.

Like Virginia, the Maryland DNR is weighing limiting all anglers to keeping one fish a day, down from two previously. But state regulators have indicated they’re leaning toward letting charter boat customers continue to keep two fish.

David Sikorski, executive director of Coastal Conservation Association Maryland, representing about 1,400 saltwater anglers, complained that the DNR is “picking haves and have nots.” He contended that if the DNR goes ahead with that option, “the charter and commercial fisheries are giving up much less than private anglers.”

Luisi acknowledged the uneven treatment. But he said that DNR officials sought to “strike a balance” that would keep the state’s 600-boat charter fishing fleet afloat.

“The one fish [limit], it would have been a death sentence for us,” said Ken Jeffries, acting president of the Maryland Charter Boat Association. Jeffries, who is based in Severna Park, said there are few other species to fish for in the Upper Bay.

“The one fish [limit], it would have been a death sentence for us,” said Ken Jeffries, acting president of the Maryland Charter Boat Association. Jeffries, who is based in Severna Park, said there are few other species to fish for in the Upper Bay.

“You’ve got to close during the time you’re killing the most to have the most positive conservation impact,” Sikorski said.

The larger problem, Sikorski said, is that the Maryland DNR is making regulatory decisions without reliable information on the state’s anglers. The East Coast states have compiled recreational catch estimates based on surveying anglers at marinas, boat ramps, beaches and other places. But the survey was designed to assess fishing activity coastwide, critics say, and it provides a much less accurate picture of what’s going on in any state or part of the year.

“We know the system we have right now is not working,” Sikorski said. “We deserve better.”

Luisi acknowledged the shortcomings of the survey, but he said it’s all regulators have to work with. He said the DNR is talking with Sikorski’s group and others about launching some type of voluntary electronic reporting for anglers that would give regulators more data to work with.

Jeffries of the Maryland charter boat association said he, too, is worried that the restrictions the DNR is considering don’t go far enough to reduce losses from catch-and-release fishing. But, he said, “this was the best plan we could come up with that was easily manageable.”