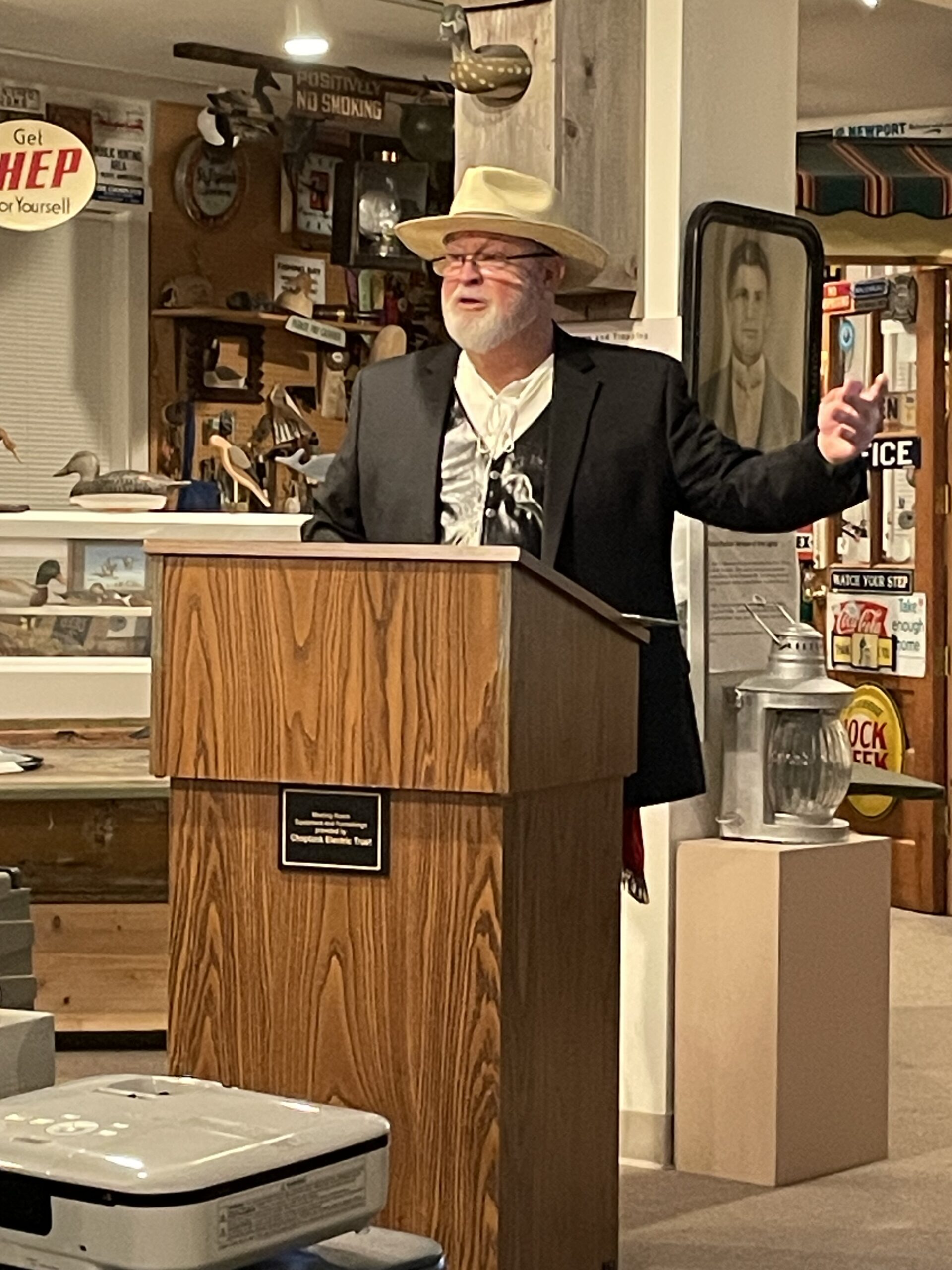

Author David Williams

The Chesapeake Bay has a long and storied history of sailing, fishing, and shipping, but not all the activities on those waters has been noble or even legal. On March 6, the South Dorchester Folk Museum hosted David Williams to present a talk on “Pirates, Privateers, and Smugglers of the Chesapeake” at the Robbins Heritage Center.

Williams, a retired Ford Motor Company employee and current Nathan of Dorchester captain, dressed in colonial garb, carried an aluminum sword, and called himself “Captain Graybeard.” While he obviously was enthusiastic about his subject matter, it was not a very exciting talk, as the “captain” mostly read off a power point presentation. But, there was quite a bit of information that would interest Eastern Shore residents and pirate buffs.

Pirates and Privateers

All through world history, there have been those who robbed people of their transported goods at sea. These pirates—also called buccaneers, freebooters, corsairs, and other names—generally focused on ships, although some made attacks on coastal settlements. Many thousands of pirates operated during the “Golden Age” of piracy between 1650 and 1720, among whom were Henry Morgan, Edward “Blackbeard” Teach, and William Kidd, the last one even spending some time on the Chesapeake Bay. Another whose activities brought him to these waters was Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts, also known as The Crimson Pirate.

But some of those mentioned wouldn’t have considered themselves pirates, but rather privateers. While a pirate was an independent “businessperson,” a privateer sailed with a “letter of marque” from his government authorizing him to steal from the vessels of other countries. This was a low-cost method for a government to increase the size of its navy, and the privateers were required to share their spoils with the authorizing body, so it was lucrative as well.

Privateers were considered a bit more “respectable” than pirates, but the truth is that one person’s privateer was the opposing person’s pirate, especially since the privateer’s actions tended to be rather piratical. In fact, many privateers came to ignore the distinctions between nations when attacking ships or towns.

William Claiborne and the Maryland-Virginia Conflict

In 1627, Virginia Secretary of State William Claiborne “discovered” an island in the Chesapeake Bay and named it Kent Island after his English hometown. Recognizing its strategic importance as a trading center, he established a settlement on the island in August 1631. At this time, the colony of Virginia extended to the northernmost part of the Chesapeake. When the king of England granted Cecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore, the territory to be called Maryland after Queen Henrietta Marie, it became apparent that there was a boundary overlap with Virginia.

Protests were raised, but they fell on deaf royal ears. However, when the ships the Ark and the Dove landed at St. Mary’s in February 1634, the new colonists kindly told Claiborne he could keep his trading post…so long as he conceded Kent Island belonged to Maryland. He apparently wasn’t happy with that arrangement, but he protested in his own way.

In the spring of 1635, one of Claiborne’s ships, the Long Tayle, attacked a small Maryland trading pinnace near Havre de Grace. The seizure of that pinnace was to be the first documented act of “pyracie” on the Chesapeake Bay. Battles commenced, people died, and ships were taken on both sides. Two of Claiborne’s men were convicted of piracy but then pardoned. Claiborne himself was sent back to England to face charges of piracy. His property was given to Lord Baltimore, who then controlled Kent and Palmer Islands.

Privateers of the Revolution

When the American Revolution began, Britain had the most powerful sailing fleet in the world. The colonial forces, however, had none at all. Without the ability to impose taxes to raise war funds, the Continental Congress had to get creative in order to develop its own navy. So, it issued letters of marque to create privateers among the patriots. And men like Robert Morris of Oxford, Maryland, provided ships for the purpose.

Colonial privateers formed a fleet of more than 2,000 vessels with 18,000 cannons and 70,000 men. They acquired $50 million for the owners and supported George Washington’s army. In fact, Morris became wealthy and was able to help finance the Revolution.

When Virginia and Maryland’s royal governors abandoned their offices and fled to the protection of British warships, the colonials took over the governments. Because only a third of the colonists supported the rebellion, the new governors were forced to impose taxes and restrictions on the citizens that were just as harsh as those of the British.

This did not sit well with the free-spirited residents of the isolated Eastern Shore, many of whom became British privateers. The most infamous of them was Joseph Wheland, commander of Britain’s privateers in the Chesapeake. He and his men wreaked broad havoc, especially on the Eastern Shore, disrupting shipping and raiding plantations. Because the Shore was producing vital foodstuffs for the Revolutionary army, Wheland made a point of destroying the food as well as homes, farms, and means of production.

When a detachment of colonial Major Fallin learned that Wheland was in the Hooper’s Strait area, they seized his ship and cargo of iron, guns, swords, and ammunition. He and his men faced many charges, and Wheland himself was ultimately convicted of piracy and having loyalist sympathies. Jailed in Frederick County until he could offer restitution to John White for the burning of his sloop, Wheland was released in 1781.

Smuggling on the Bay

In order to raise money from its colonies, Britain imposed import duties, which strangled commerce and dampened trade and competition. So, many colonists chose to circumvent the laws. Britain labeled colonial smugglers as pirates, who could be taken to London, tried, and inevitably executed. Those on land who helped the smugglers faced the same fate. The colonists were not to be cowed, but they did have stiff competition in the form of the East India Company, which was the only official importer of tea to the colonies in the early 1770s. Because the cost of tea was reduced, the smugglers protested by arranging the Boston Tea Party and the Chestertown Tea Party.

Civil War increased the opportunities for smuggling on the Eastern Shore. Many of its residents were sympathetic to the Confederacy, and they smuggled various goods through the federal blockade to the South. There was also smuggling on the other side of the conflict—human smuggling—as the Underground Railroad helped runaway slaves escape north.

Passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920 brought about Prohibition, which outlawed the manufacture, transport, and sale of alcohol. This gave rise to the smuggling of liquor from home breweries, stills, and abroad. This illicit manufacturing thrived on the remote Eastern Shore, where many of the inhabitants were involved in the business.

The Chesapeake Bay was the perfect place for “rum running,” thanks to its miles of shoreline, rivers, and inlets. The Coast Guard, who was chiefly responsible for stopping smugglers there, found it impossible to properly police 11,684 miles of coastline. While large liquor-bearing boats from overseas waited past the three-mile limit, small craft pulled alongside at night or when the Coast Guard boats were elsewhere, loaded up, and snuck back into the Bay. Then they would travel to a drop-off point to meet a car or truck that would whisk the booze off to the cities.

The fastest rum-running boats were the 53-foot-long Whippoorwill and the 56-foot Hiawatha. With its three 450-horsepower motors, the Whippoorwill could not be caught. But, in May 1931, federal and county officials ran a sting operation at Taylor’s Island, which had been a rum-running base for more than a year and had a radio operator for giving directions to the smuggler boats. The Whippoorwill and Hiawatha were caught, netting the government 14 prisoners, a fleet of trucks, and 6,000 cases of liquor.

Conclusion

While piracy still exists in the world, it has pretty much disappeared from the Chesapeake Bay, where it is no longer in demand. But the memories remain, in oral and written form, and occasionally they’re brought out by folks like David “Captain Graybeard” Williams to be experienced once again.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.