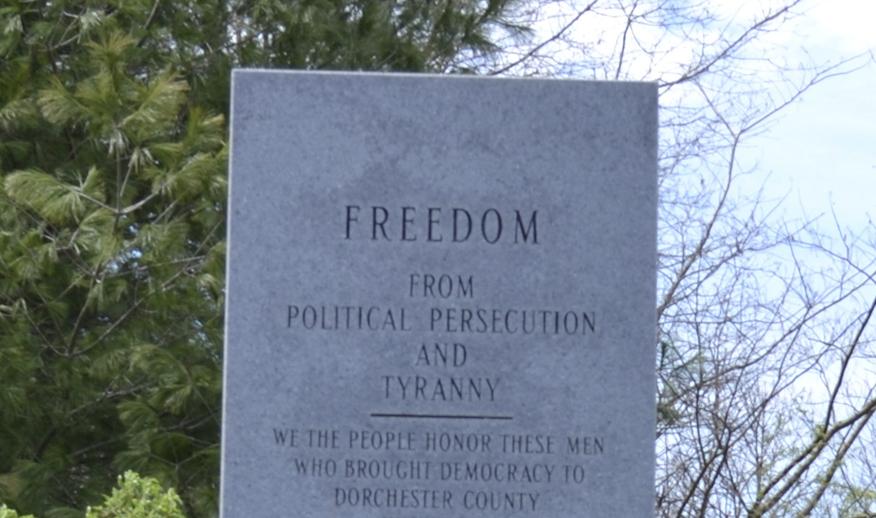

The large blue-granite monolith is easy to miss, as it stands within a chain link fence on the side of the road between Preston and Hurlock on MD 331. Ironically, a slab jutting out at the base reads “Lest We Forget.”

“I think we have forgotten,” said Cambridge resident Chuck McFadden mournfully.

The Historical Freedom Shrine, as it is officially known, is dedicated to ten Dorchester County men who brought about local and state voter reform in Maryland by challenging the injustices in the political process and leveling the playing field for minorities. It’s strange to see such a significant monument in such an obscure place, and there are some people who think it should be moved somewhere more prominent so everyone can see it and understand the reason for its existence.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, new federal laws were passed to outlaw various forms of discrimination against minorities, and among them were voting rules. But, into the 1980s, the five county commissioners of Dorchester County were elected using an “at large” system, in which the winners were the nominees who got the most votes from the entire county. This meant that all the council members always came from the most populated area—Cambridge—and were always white.

The same thing applied to the city council of Cambridge itself: because of the at-large election rules, it was very difficult to elect a Black commissioner, even from the largely Black Second Ward. And, since at least 1882, the boundaries of that ward encompassed all but one of the blocks where African Americans lived. According to the 1960 census, the Second Ward had over ten times as many people as the all-white Third Ward. The next year, the City redistricted to equalize the population of all the wards except the second. As a result, Black electoral participation was basically fixed to that voting area, thus depriving those residents of true representation.

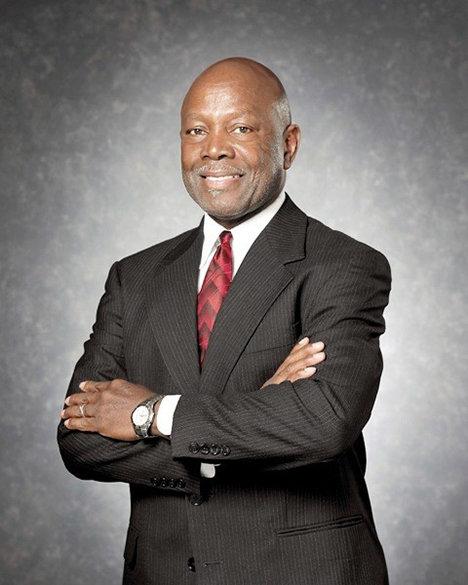

“I went back and looked at the city and how they had the streets divided in wards,” said Greg Meekins, one of the men whose names are on the monument. “And streets specifically said ‘Whites Only.’ This was prior to the 80s, but because it was in place so long folks just assumed that you don’t move out.”

“It’s just inconceivable that anybody could come up with a system like that,” said McFadden, “where they pushed everybody into one ward and the wards were not equal.”

Concerned that the at-large system made it extremely difficult to elect anyone from the northern part of the county, some people got together in 1980 and raised litigation funds. The following year, an action committee called the North Dorchester Democratic Club was formed by a group of influential men, led by George C. Jones, who determined that the county commissioners could and should be elected by districts. The club approached Meekins, who at the time was president of the Cambridge branch of the NAACP, and they forged a partnership.

“We thought it was an opportunity to enlarge minority representation,” Meekins remembered. “So, that’s why we got involved.”

In November 1983, the club filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice that the 1964 Voting Rights Act was being violated. After depositions by the members, the DOJ filed United States of America v Dorchester County Board of County Commissioners in U.S. District Court in Baltimore.

The following May, the Department was made aware of the county seat’s voting practices, and in December 1984 United States of America v the City of Cambridge declared that the City’s at-large system violated Section Two of the Voting Rights Act as well as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Alleging that Cambridge had adopted the at-large format in order to dilute the voting strength of its Black citizens, the government asked the district court for an injunction preventing the City from conducting future elections under that system. The court ordered the defendants to come up with a plan for meeting the requirements of federal law.

Cambridge finally agreed to a consent decree, and settlement negotiations started in June 1985. A DOJ attorney told the City that the government sought a racially fair election plan. The outcome was the establishment of a new format that was approved by the Court and the DOJ. It included the stipulations that commissioners must reside in the ward they represent, they must be elected by the voters of that ward, and the voting population of each ward must be approximately the same. Similar requirements were established for Dorchester County elections.

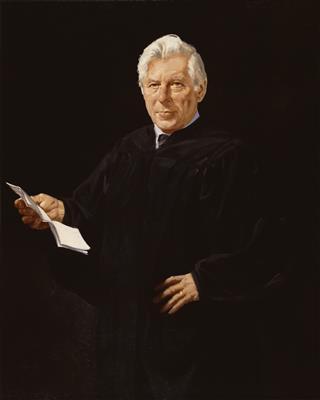

On July 8, 1985, Judge Norman J. Ramsey ordered the creation of five equal voting districts, abolished at-large voting, and signed the consent decree. In 1986, the Maryland legislature amended the state constitution. The results were the election of the first Black county commissioner in Dorchester history and the broadening of Black representation on the Cambridge City Council.

To immortalize the efforts of the North Dorchester Democratic Club, George Jones had a 20-ton monument created in 1987. The inscription includes the names of all ten men: Jones, Meekins, Charles F. Hurley Sr., Don W. Bradley, Oliver Harding, Richard Harding, William Reid, Edward Conway, William O. Corkran, and Leon Medford. The monument also offers information about the events that led to the end of at-large voting in Dorchester County. It is an impressive shrine deserving a place of honor.

However, because of a backlash of feelings about the voting rights cases, the local government could not “find” any public land—in Cambridge or the county—on which to put the monument. So, Jones had it installed on his own out-of-the-way property. It was erected on November 10, 1987.

After Jones died, the land was sold twice, and the current owner put up the fence around the shrine to keep people out. According to Meekins, curious visitors have “caused a little pain for [the owner] and his family.”

“I think it’s a shame that it’s sitting out there,” lamented McFadden. “There’s no parking, you have to just pull up to the side of the highway and walk around a drainage ditch to get to the fence that surrounds it.”

In an attempt to remedy this, Dr. Carl Barham started going to the state legislature annually to keep the monument in the public’s view. His goal has been to see about moving it to a more centralized location, such as Cambridge or Hurlock. At one point, Meekins was interested in having it placed at North Dorchester High School, and he even approached the Board of Education about adding the lawsuits to the history curriculum so students would learn to be vigilant and keep their eye on what happens with voting rights in America. Generally, though, Meekins prefers to remain in the background. But he and Barham keep in touch.

McFadden knew none of this when he began researching the Cambridge City Charter “because of what’s going on with the City Council and people living outside of their wards.” He happened upon the voting rights case, which he had only vaguely heard of, even though he served with Meekins on the city’s ethics commission for several years.

“I thought it was back in the sixties, during the riots and all that kind of stuff,” said McFadden. “I didn’t realize it was ‘85, and I also didn’t realize it was ‘85 when they had this disproportionate ward system.”

Then, during Black History Month this year, Mayor Steve Rideout called Meekins and said, “I thought about that monument and would love to see it moved.”

Meekins was pleased that there was some interest in the project. But it had to wait until he investigated some of the technicalities surrounding the monument’s ownership. He didn’t know if Jones had included anything about it in the property’s deed before he died.

“As soon as we find out what the technicalities are,” explained McFadden, “I would like to approach both the county and the city to find funds to move it. It is a big object, not something you can put on the back of your pickup and move. This is big. But, if they could put it out there, they can put it anywhere they want.”

If funds are not available for moving the monument, McFadden will be happy to lead the effort to raise the money needed for the move, a new place to put it, and a rededication.

“So, I don’t know what it’s going to take,” he said. “It’s going to take some effort, but I’m retired.”

McFadden thinks it’s important to “make amends” for the neglect of the monument and its reason for being. “It’s just as important to me as the riots in the 60s, maybe up there with Harriet Tubman.”

“It’s a part of history,” said Meekins. “And, ironically, despite all the black eyes Cambridge and Dorchester County get, we’ve been a trendsetter in the state as far as activism in the community, more so than some other counties.”

The monument was important enough for Governor Larry Hogan to visit it a few months before he left office—the first Maryland governor to do so. He and Meekins took some photos together with it. Hogan recognized that the triumph of the North Dorchester Democratic Club needs to be remembered.

In November 2014, Dr. Barham said, “The works of ten bold, brave men should not be minimized or go in vain, because their passion and vigilance changed the political landscape of Dorchester County.”

Totch Hartge says

Tell us how to help

Totch Hartge

Easton

Lorraine Claggett says

Dorchester County has a legacy here, among others, of which it can be proud. Let the local folks find a suitable place and recognition for their leaders of today who carry out the promises of freedom established to begin our nation.

JoAnne Wingate Nabb says

This is a very important article. I truly hope this monument gets the attention it truly deserves and is relocated to a proper home for everyone to see. Thank God we have brave, righteous and caring people who give of themselves.