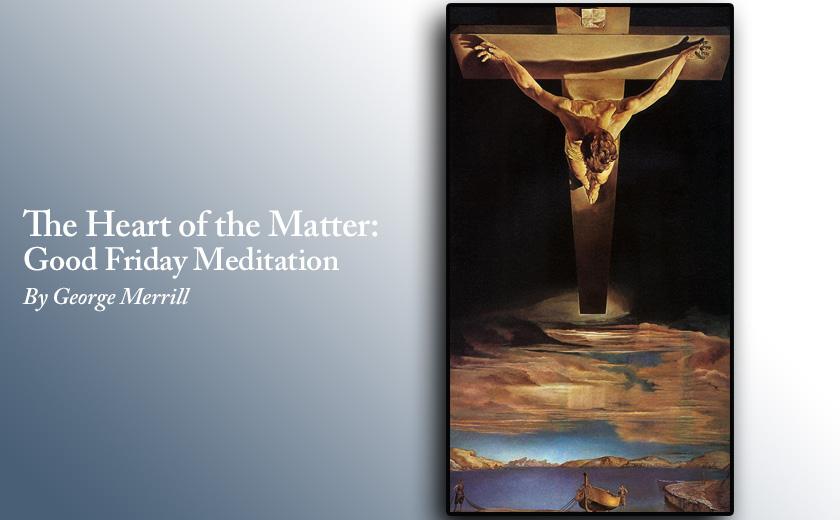

The crux of an historic religion is its stories. The stories guide, direct, inform and inspire the faithful. We call those stories myths. By myths we mean not that they’re make-believe, but that they strike to the soul of our human condition. Mythical images reflect eternal truths.

I have sometimes wondered about one of the Christian stories. I’ve struggled at times to see how it could guide, direct, or comfort me in any way. It is the Good Friday epic which, I confess at times, I haven’t seen as very good at all. It’s very heavy. It’s complicated. It has to be one of history’s most egregious accounts of both political and religious treachery and deceit, accompanied with a level of brutality and humiliation equal to the holocaust. It is one of humanity’s horror stories.

Over the years I have come to see the observance in a clearer light. There is something very good about it, some things we desperately need to hear. I would go as far as to say our survival will depend in it.

As the Good Friday story unfolds, it begins to suggest a scenario not unlike Dr. King’s marches that spoke truth to power. King’s message had been creating backlashes from not only law enforcement agencies, but also some religious institutions invested in white supremacy. Speaking truth to power can be dangerous. King’s rallying cry was “Set my people free.” Jesus message was, “Love one another as I have loved you.” Like Jesus, King’s message of love and reconciliation were not universally welcomed. In fact, people grew nasty, and brutally violent at times.

Christians understand Jesus as the one who reveals to them just what God is really like. He helps us see beyond the generalities into the particulars of God’s spirit, the nuances if you will. So, Christians remain attentive to Jesus by watching what he does as well as what he says.

I believe this is one way that God leads us.

Which brings me back to the Good Friday epic.

In a telling incident, I believe the nature of God is clearly revealed, and we see what God is like and what he wishes from us. God is very strong and at the same time, remarkably kind and gentle.

The incident takes place in a garden near a brook at Cedron. Judas brings with him armed officers and officials of the high priest to arrest Jesus. “Whom do you seek?” Jesus asks. When they say, Jesus of Nazareth, he tells them that he is the one. Then this happens:

“Then Simon Peter having a sword, drew it, and smote the high priest’s servant and cut off his right ear.”

Jesus rebukes Peter, saying, “Put up thy sword into its sheath; the cup that my father hath given me, shall I not drink?”

I understand the incident in this way; that whatever means that Jesus may wish us to employ or that he would himself engage in the furtherance of his Kingdom, violence and the use of weapons is not among them.

To state the divine imperative in another way that speaks to our own time: our faith teaches us unambiguously that stopping a bad guy with a sword, with a good guy with a sword, is not a Christian’s way.

There’s one other piece to the story. Considering all the brutality, humiliation, and injustice visited on Jesus, he exhibits a gentleness of spirit and moral courage that is extraordinary. At the end of the day he can still say “Forgive them, Father, for they don’t know what they are doing.”

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.