As remarkable and important as the Water’s Edge Museum collection of Ruth Starr Rose paintings and prints may be, its provenance is even more so. Dating back to a time when women had just recently won their right to vote and when Jim Crow laws sought to deny all human rights to African-Americans, Rose – a white woman – created, as she put it, “a record of the life of Negroes of the Eastern Shore. It had never been done,” she wrote, “and is still unique in the annals of art.”

Bernard Moaney as a duck hunter, 1931

While art depicting people of color is no longer “unique” to this collection at the museum located on the Tred Avon’s edge in Oxford, it most likely was the case in 1933 when she wrote about her work. Moreover, it’s hard to imagine that anyone else could have achieved such a legacy. In the early decades of the 20th Century it was rare for black artists or women artists of any color to gain much notice. And her access to an isolated community with every reason to mistrust white strangers is itself remarkable. There were black artists whose success at the time was hard-earned – from Jacob Lawrence in fine art to Paul Robeson in performing arts – they won their notoriety in metropolitan capitals of the United States, principally New York City.

By comparison, Rose, the daughter of staunch Wisconsin abolitionists, won the trust of all-black communities of Talbot County at a time when the Eastern Shore – before any Bay Bridge was even dreamed of – was a geographic backwater. Yet she made friends with residents of The Hill in Easton, the historic neighborhood of free African-Americans dating back before the Civil War, as well as Unionville and Copperville settled by veterans of the war that won their emancipation.

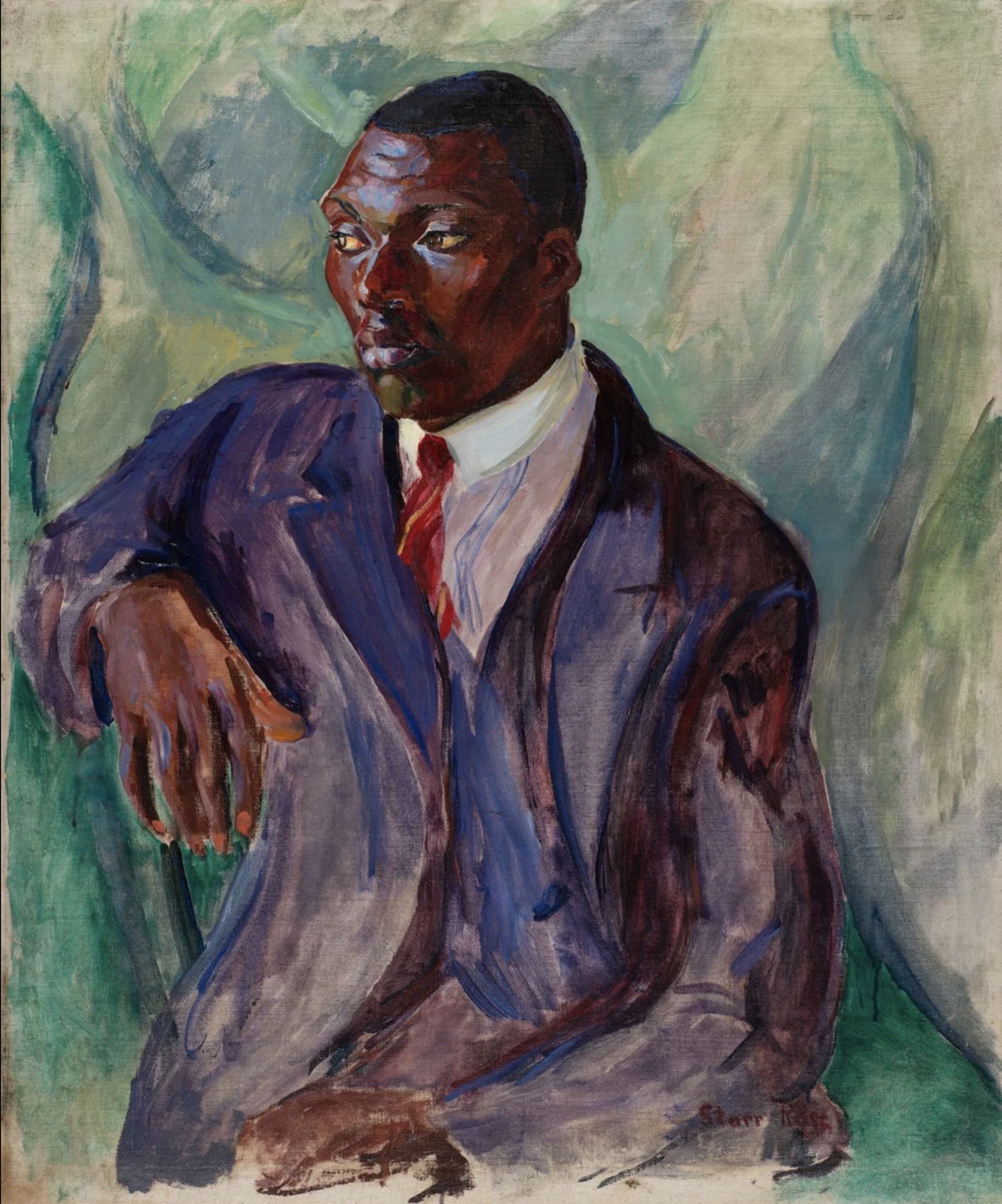

Rose attended their AME churches regularly and developed her appreciation of spirituals performed by people she regarded as friends and neighbors. Among the oil portraits she painted were those of Isaac Copper, namesake of the founding family of the village bearing his surname, and Bernard Moaney, whose descendant, George Moaney, narrates the five-minute video “The Afterglow of Ruth Starr Rose” by Talbot Spy that can be seen on the Water’s Edge website, You Tube or talbotspy.org. He’s also a founding member and genealogical adviser to the museum.

Even in major museums of the world, George Moaney notes, “You don’t see a black person in their paintings except in the background as servants” or, more recently, in portraits of celebrities and political figures, notably Muhammad Ali and President Barack Obama. Before 2015, when the Rose collection surfaced, “Our family didn’t even know these images existed.” The unveiling of the works by Rose (1887-1965) marked, he said, “the first time I had seen on the Eastern Shore black and white people coming together for a cultural event.”

Of her 1933 color serigraph “Jonah and the whale,” featured four years later at the Paris International Exposition, Rose wrote: “Long ago the slaves sang, ‘If the Lord delivered Jonah from the belly of the whale, He will deliver me.’ And these words came too: The Negro race has been delivered from dangers and torments worse than Jonah knew. They have been given a vision of the freedom that can finally be complete.”

But there is much more to see and experience at the Water’s Edge Museum. In its special exhibits gallery, “Black Watermen in the Chesapeake” opens later this month. In the hallway just outside, pause to view “Victoria Park as a Civil Right.” In 1848, about a decade into her 63 years and seven months reign – surpassed only by the 70-year monarchy of Elizabeth II – Queen Victoria granted an “urban botanical garden” for the people of Antigua and Barbuda, part of the British Empire until 1981. The garden, she wrote, serves as open space “for the healthful enjoyment of air and space” for the people of the Caribbean island colony – now a nation.

Be sure, then, to step outside to the Water’s Edge botanical garden. Replete with flowers, plus basil, bell pepper, cucumber and tomato plants, the fruits of which are composted. Besides the staff, the garden is tended, in part, by visiting elementary to middle school children who “learn about environmental justice that is denied to those who live in food desert neighborhoods,” said Sara Park, co-director of Water’s Edge along with Ja’lyn Hicks.

Water’s Edge was awarded a certificate of recognition from the Talbot County Council for the “pictorial history and artifacts on display [portraying] a resilient people who lived their lives, and loved and fought for their country and continued to forge ahead, despite the obstacles and hardships faced.” Council member Keasha Haythe, who had attended the museum’s anniversary celebration earlier in February, commented on the recognition: “Thank you for telling these stories. Having a grandfather who was a waterman, it’s important to tell stories of the heritage, history, and diversity that we have in Talbot County.”

Coincidentally or not, this occurred at the same council session in which a motion to rescind the county’s declaration supporting the goals of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) was defeated. However, following Trump administration threats to deny federal funding for expansion of the Easton Airport, the council voted in June to delete all mention of DEI goals in its official statements.

Isaac Copper in a suit, 1931

Nevertheless, Kay Brown, the museum’s assistant director, continues her work as manager of the Middle Passage Port Marker Project. Oxford is the only UNESCO-documented Middle Passage port on the Eastern Shore with no sign declaring that this is where slave ships docked to deliver its human-bondage cargo for sale. It’s a distinction shared in part just across the Tred Avon River where the Bellevue Passage Museum is planning and raising funds to build a space to tell the story of one of the country’s oldest African-American waterfront communities, which became self-sufficient following the Civil War abolition of slavery. The goal is to add on to one of the few remaining historic buildings available, located next to the Oxford-Bellevue Ferry dock. For now, the museum is a virtual one where you can view photos, artifacts and documentation of Bellevue’s own water’s edge past. In partnership with the museum in Oxford, the two would comprise a ferry-linked match in presenting an immersive educational and heritage tourism experience.

***

For more on slavery to self-sufficiency and the Eastern Shore’s witness to both, the Harriet Tubman Freedom Center in Cambridge is exhibiting “Harriet: A Taste of Freedom” through Sept. 30. Curated by Larry Poncho Brown, a Baltimore-based artist, through interpretive works by 40 artists whose visions know no bounds as they are both local and international. The art ranges from portraiture to abstract imagery. In that sense, it’s almost as varied as Tubman’s remarkable life’s work – starting as a runaway slave herself who returned time and again to free family and other fellow slaves in Dorchester County to freedom at least as far north as Philadelphia. And she literally fought for freedom in the Civil War, having recently been promoted posthumously to the rank of general.

While you’re at it, and especially if you haven’t already visited, drive a few miles out of town to the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park. The visitors center there serves both as a stand-alone attraction with exhibits and films changing from time to time with the goal of orientation as a gateway to the multi-state Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway. Tubman is quoted as saying, “I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

FROM RUTH STARR ROSE TO HARRIET TUBMAN

Water’s Edge Museum, 101 Mill St., Oxford. watersedgemuseum.org; Bellevue Passage Museum, online only bellevuepassage.org

Also, “Harriet: A Taste of Freedom,” Harriet Tubman Freedom Center, 3030 Center Dr., Cambridge, through Sept. 30 (possibly extended through December); harriettubmanfreedomcenter.com; Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitors Center, 4068 Golden Hill Rd., Church Creek, nps.gov/htu

Steve Parks is a retired New York arts critic and editor now living in Easton.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.