The Chesapeake Bay is known to many for the seafood it produces: blue crabs, oysters and striped bass.

In a few years, though, the Bay region could become a major producer of an even more popular seafood that doesn’t come from the Chesapeake. A Norwegian company, AquaCon, has unveiled plans to raise salmon on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

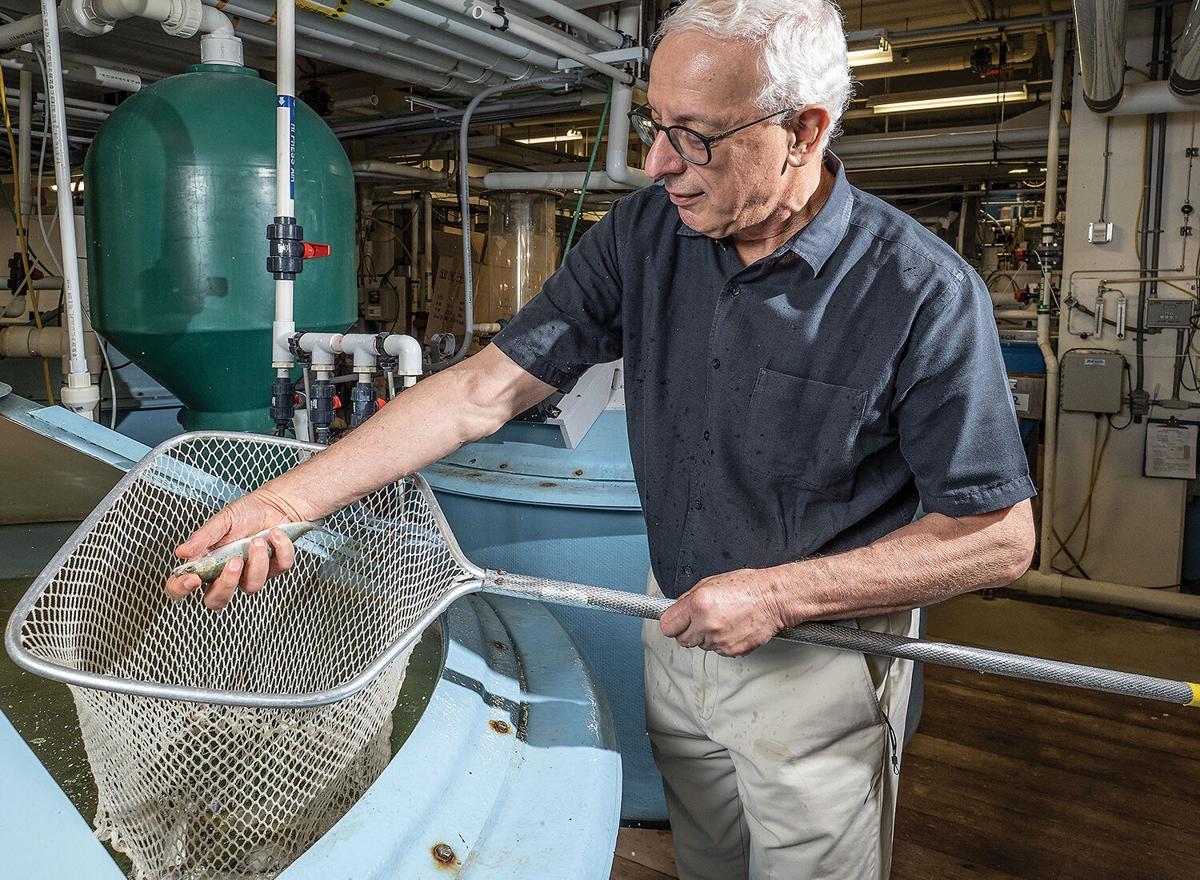

Yonathan Zohar, head of the Aquaculture Research Center at the University System of Maryland’s Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology, shows salmon being raised in tanks in Baltimore. Dave Harp

AquaCon executives intend to build a $300 million indoor salmon farm on the outskirts of Federalsburg in Caroline County. By 2024, they aim to harvest 3 million fish a year weighing 14,000 metric tons — an amount on par with Maryland’s annual commercial crab catch.

If that goes as planned, the company expects to build two more land-based salmon farms on the Shore over the next six or seven years, bringing production up to 42,000 tons annually. That’s more than the Baywide landings of any fish or shellfish, except for menhaden, and more valuable commercially.

AquaCon’s announcement comes amid a rush by mostly European aquaculture companies to supply Americans with farmed salmon. Another Norwegian company is preparing for its first full harvest later this year from a facility south of Miami, and plans have been announced to build big indoor salmon farms in Maine and on the West Coast. Two small U.S.-based salmon operations in the Midwest also are moving to expand production.

It’s not hard to see why. Next to shrimp, salmon are Americans’ favorite seafood. They each eat more than 2.5 pounds of it annually, according to the National Fisheries Institute. Experts think that appetite could double over the next decade. And right now, more than 90% of the salmon consumed in the United States is imported. Most is Atlantic salmon produced by aquaculture operations in Norway, Chile, Scotland and Canada.

Atlantic salmon, which can grow to 30 inches and weigh 12 pounds, once spawned in every East Coast river from New York north into Canada. But fishing so depleted the stock in U.S. waters that the fishery was shut down in 1948. It’s never recovered, and the species is listed as endangered.

Traditionally, most imported salmon has been raised to market size in open sea pens. But that has several environmental downsides. For example, growers have used antibiotics, pesticides and other chemicals to fend off sea lice, a major problem, along with other parasites and diseases.

Also, uneaten food and fish waste increase nutrient levels in open water, which can deprive aquatic life of the dissolved oxygen it needs to thrive and survive.

In recent years, facing increased production costs and more regulatory limits on open water aquaculture, salmon farmers have begun trying land-based aquaculture, using recirculating technology that’s been utilized for years to raise other fish in tanks.

AquaCon executives say their technology will keep their salmon free of parasites and diseases without drugs or chemicals. It will also prevent water quality impacts, they say, by treating and reusing nearly all of the water in which the fish swim.

“This is really the first true green aquaculture project in the world,” said Henrik Tangen, AquaCon’s chairman. “That’s what we’re trying to achieve here.”

Tangen said he and the company’s top executives are mindful of the need to minimize environmental impacts in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

“We know we are in an environment where we need to be cautious of any natural resources we are using,” he said.

‘Biodigester’ technology

“There is a huge opportunity here for domestic production,” said Yonathan Zohar, head of the Aquaculture Research Center at the University System of Maryland’s Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology.

To Zohar, the AquaCon venture is the fulfillment of a dream. He’s spent nearly three decades working to make fish farming more productive and sustainable, raising small batches of striped bass, salmon and tuna, among others, in tanks. But until now it hasn’t brought large-scale aquaculture to Maryland.

“Now we believe the technology is finally mature,” Zohar said, “and able to be scaled up in a way that is economically feasible and … environmentally responsible.”

The AquaCon team chose to build on the Eastern Shore because of its proximity to mid-Atlantic markets, but the institute’s nearby expertise helped cement that decision. Executives say they have a formal partnership set up to work with the institute as plans move forward.

Farmed salmon traditionally have been raised to market size in open sea pens. Parasites, disease and regulatory limits have fueled a shift to land-based aquaculture, particularly to supply a growing U.S. demand for the fish.

At the institute’s Baltimore laboratory, the sludge that settles on the tank bottoms from uneaten food and fish waste is siphoned off into an anaerobic digester, converting 70% of it into methane gas.

Tangen said AquaCon plans to treat its sludge using Zohar’s “biodigester” technology. The company also wants the institute’s help to develop a more sustainable diet for its salmon — one including algal oils and protein from insects. Another rap against traditional aquaculture is it requires harvesting a lot of wild fish to feed the farmed ones.

AquaCon’s salmon-rearing facility would have one of the largest building footprints on the Delmarva Peninsula. Containing 25 acres of space under a single roof, the facility will be roughly the combined size of six Walmart Supercenters.

As to the site, AquaCon is moving to purchase a 200-acre farm just outside Federalsburg. The property, currently composed of chicken houses and cornfields, will be annexed by the town to get access to its sewer lines, if the company gets its way.

The salmon will spend their lives swimming in circles in a complex of 127 tanks. Mimicking their natural life cycle, which involves migrating from rivers to the ocean and back, the fish will start out in freshwater tanks and finish their grow-out in tanks with salinity levels similar to the Mid Bay’s. Salmon can reach market size (about 11 pounds) in about two years that way, faster than if raised in sea pens.

The water in the tanks will be recycled after being treated to filter out ammonia, using technology that reuses more than 99% of it, company executives said.

“Our objective is to optimize the water usage so we don’t have any waste,” said Bob Rauch, the project’s Easton-based engineering consultant.

The handling of wastewater

The Federalsburg facility will still need a vast quantity of freshwater initially to fill its tanks – 49 million gallons, enough for 74 Olympic swimming pools. After that, the operation and processing of harvested fish will only require about 70,000 gallons a day from an onsite well to replace what is lost through its waste treatment systems.

The chicken farm currently operating there is permitted to pump more than 10 times that amount, according to Rauch. But at times, AquaCon may need to double or even triple the current well’s permitted withdrawal rate. Company executives say they believe there is ample groundwater to do that, but would require approval from the Maryland Department of the Environment.

On the edge of the small community of Federalsburg, MD, a proposed indoor salmon farm would sprawl for 25 acres under a single roof. Jeremy Cox

AquaCon hopes to pipe 70,000 gallons of treated wastewater daily from its operation to Federalsburg’s municipal wastewater treatment plant. That facility can process up to 750,000 gallons per day but now uses only about half of that capacity to serve the community’s 2,800 residents.

Lawrence DiRe, the town manager, said that the developers haven’t formally submitted any plans to the town. But if they jibe with what has been publicly presented so far, the wastewater plant should have no problem handling the additional flow, he said.

Federalsburg’s wastewater plant discharges into Marshyhope Creek, about 15 miles upstream from where it drains into the Nanticoke River, a Bay tributary. In 1996, the MDE declared the Marshyhope impaired by nutrient pollution, pointing to the overfertilized cropland that abuts much of its course.

Despite the nutrient problems, scientists and fishermen have discovered that the creek and the Nanticoke River harbor a spawning population of endangered Atlantic sturgeon. The state is conducting a tagging study to monitor the rare, prehistoric-looking fish.

Rauch said environmentalists have expressed concern that the aquaculture complex might upset the waterway’s ecological balance, harming the sturgeon. He vowed the company would take any actions required by environmental regulators to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Federalsburg’s wastewater plant itself has a spotty regulatory history, though, with a handful of violations the last three years, including exceeding discharge limits on phosphorus and E. coli bacteria. The town manager said the plant was run then by an outside contractor, but the town has since taken over.

AquaCon may need to dispose of additional wastewater if it has to purge its fish of a muddy flavor that can plague tank-reared salmon. Tangen said that the technology they plan to use should avoid that problem. But if needed, Rauch said the facility would seek MDE permission to spray the extra treated wastewater onto the land the company is acquiring.

AquaCon’s Tangen noted other “green” features of its project, including the installation of solar panels on the sprawling roof and the methane its waste digester will generate, which could be burned or sold to generate power. And by locating in Maryland, he said, the company will be reducing carbon dioxide emissions used to get its salmon to U.S. consumers, compared with those shipped in from abroad.

Salmon swim in a tank at the Aquaculture Research Center at the University System of Maryland’s Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology in Baltimore.

Dave Harp

Company executives have met with state environmental regulators to explain their plans. MDE Secretary Ben Grumbles wrote AquaCon’s Tangen in June that he is “very encouraged” by the company’s plans and “welcomes the opportunity to support projects that are environmentally responsible and sustainable.”

The amount of groundwater requested by the company is “within a reasonable range,”Grumbles added, though testing would have to confirm it.

The MDE also would need to approve the company’s plans to control stormwater pollution, and agency spokesman Jay Apperson said an air pollution permit tied to the anaerobic digestion operation may also be required.

Can it succeed?

AquaCon’s Federalsburg operation is expected to create about 150 jobs, company officials said. Although it would be located in the Shore’s only land-locked county, it’s a good fit for the predominantly agricultural region, said Debbie Bowden, Caroline County’s economic development director.

“Anything that grows is in our DNA,” Bowden said. “With the cutting edge technology of the aquaculture … it creates an opportunity for more jobs and more economic activity.”

Whether it all comes together remains to be seen. While there’s a lot of buzz around land-based salmon operations, industry experts say they have yet to prove they can reliably turn a profit and compete with traditional openwater fish farming.

All of the salmon facilities announced in the United States call for massive injections of capital, and experts predict some won’t be able to get off the ground. They also warn that glitches in the water purification systems could cause large numbers of fish to die; a large indoor salmon farm in Denmark experienced a big die-off earlier this year. And recirculating systems require a lot of energy to run.

What’s needed is a “major success story,” said Brian Vinci, director of the Freshwater Institute, an arm of the Conservation Fund that works to make aquaculture more environmentally responsible. The institute’s laboratory in Shepherdstown, WV, has been raising a small batch of salmon in recirculating tanks for years to refine the technology.

“We need someone to show that, at this massive scale … they can succeed biologically and can succeed economically,” Vinci said during a recent webinar, “and can do it while maintaining all the sustainability benefits.”

AquaCon’s executive team believes it can do that. First, though, they need to come up with $300 million to build the Federalsburg plant, and $1 billion for all three facilities. This is the first such operation for the company, which was only formed last year.

But Tangen is confident they’ll attract enough investors, because the firm’s management team has decades of experience in financing, designing, building and operating aquaculture facilities in Norway and around the world.

Above all, he said, they’re aiming to develop an operation that can produce “American Salmon” — their brand name — with a reputation for environmental responsibility.

“We’d like to have a product that people relate to in a positive way,” he said, “that is something they want to give their children and something they believe … to be a sustainable type of production and product itself.”

By Tim Wheeler and Jeremy Cox

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.