Editor’ Note: This story was written for the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Dick Cooper

Standing in the living room of his home overlooking the Honga River just north of the hamlet of Wingate, J.C. Tolley points out a wooden sign he has displayed on a coffee table.

It brings back a rush of bad memories from the day in 1958 when famed boat builder Bronza Parks was shot to death.

“I was there right after it happened and saw Bronzie laying there shot in the head,” says Tolley, a retired seafood purveyor.

He says word of the shooting spread quickly through the close-knit watermen’s community and soon most of the men from the area – news accounts put the crowd at 150 — were milling around the large B.M. Parks’ boat shop 500 feet from the water.

“The sheriff came and took the killer away,” Tolley says. “The men were getting ready to lynch the guy.”

The murder of Bronza Parks is still one of the most memorable and often told crime stories of the Eastern Shore with legal proceeding dragging out for more than a decade. In many ways it is a story about the contrasting lives of two Maryland men from different worlds; Parks, the victim, and Willis Case Rowe, the killer.

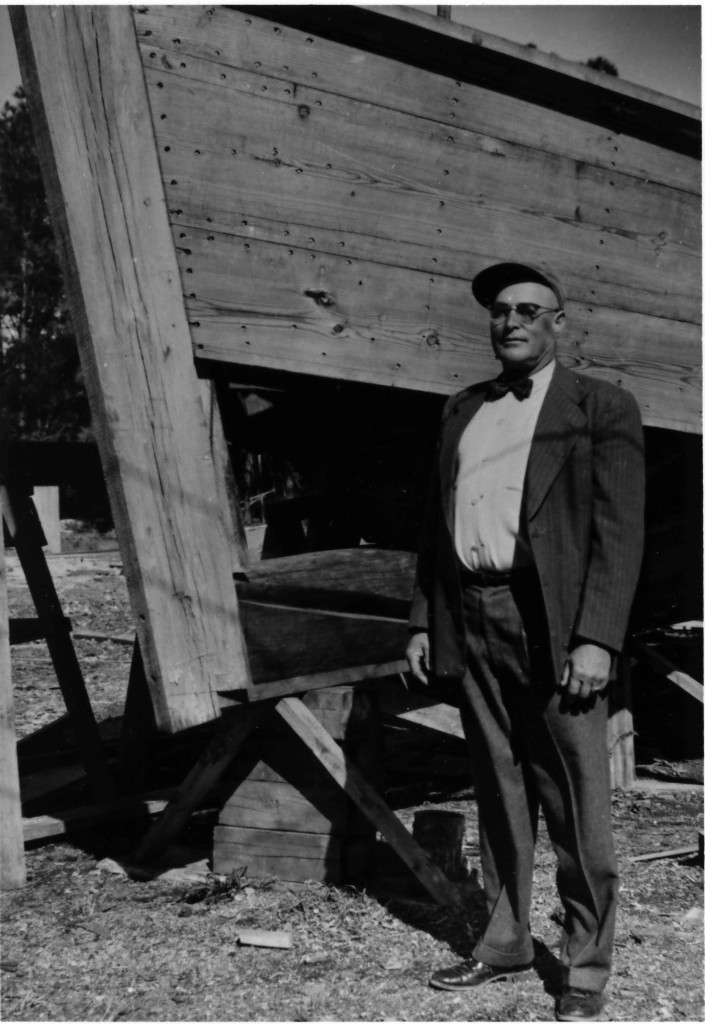

Parks, 57 when he was killed, was a big man in Wingate in more ways than his imposing physical stature. He came from a large extended family that had deep roots in the area. He was one of the largest land-based employers in the area.

“He would hire anyone who could drive a nail and use a paintbrush,” William “Snooks” Windsor says. Both he and his brother, O’Neal, worked for Parks as young men and both recall the day Parks was shot. Snooks, who now runs Pawley’s Marina, calls it the worst thing that ever happened in Wingate.

Parks was the founder of the Lakes & Straits Volunteer Fire Department and had donated land next to his boat shop for its first building. His daughter, Mary Parks Harding of Cambridge, says that her father was upset by the accidental electrocution of a local worker who survived the initial shock but died later.

“Dad thought that if we had an ambulance, that man would have survived,” she says. She said he began a drive to raise money to buy an ambulance and that was the impetus behind the starting of the fire company.

The current fire house is on land where Parks’ large boat shop once stood. It was in that boat shop that Parks and his crew built the Chesapeake Maritime Museum’s famed skipjack Rosie Parks. The Rosie, built for his brother Captain Orville Parks and named for their mother who died when they were children, is being rebuilt on the CBMM campus by Project Manager Marc Barto as part of a three-year education and demonstration project financed by contributions from Museum members.

Parks was also active in local Democratic politics and in January of 1958 announced his candidacy for the office of Dorchester County Commissioner. According to contemporary newspaper reports researched by Dorchester County writer Hal Roth, earlier in the day on May 13, the day he was shot, Parks had been campaigning in the northern part of the county promoting a rally the next night at the Lakes & Straits fire hall.

Parks reputation as a premier boat builder was known around the Bay. He had built more than 400 vessels including skipjacks, work boats and pleasure craft. Willis Case Rowe, a 39-year-old lawyer, writer and researcher for the influential U.S. News and World Report magazine, had contracted with Parks to build an 18-foot skipjack replica. Parks, who was building the boat on a time-and-material basis, had stopped construction until he was paid.

Rowe, who lived with his wife and young daughter in Silver Spring, was a World War II veteran whose capture by the German’s near the end of the war left deep emotional scars. His defense lawyer would later argue that he had been suffering from mental illness ever since his capture.

Rowe was an Army captain when his battalion commander surrendered his unit to the Germans. In an essay entitled “Ethics of Surrender” published in The Infantry Journal after the war, he wrote of his shame and embarrassment for not fighting to the death and gave insights into his internal struggle.

“During those last moments, when grenades were crashing around the cellar door and men began whispering surrender, something inside me rebelled. I could have yelled for them to follow and rushed out into the street. They might have followed. But I waited too long and the battalion commander passed the word to surrender. Then it was too late,” Rowe wrote.

In another passage he wrote, “As we marched out of the gutted village in the gray dawn, I had heard American machine guns firing in the far end of town. Some of those kids, who hadn’t thought of surrendering, were still holding out, selling their lives dearly, while, unknown to them; the surviving remnants of their outfit were marching off to captivity.”

After the war, Rowe, a slight, studious man, returned to Maryland and enrolled in George Washington University. He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1949, a law degree the following year and his master’s in law degree in 1952.

His career took him first to the Library of Congress were he worked in the copyright department and then to U.S. World and News Report where he worked directly for the editor-in-chief. That was the job he held when he drove to Wingate on May 13 to talk to Parks about what he owed on the boat. (After his arrest, the Sheriff’s Department described Rowe as a traveling magazine salesman from the western shore.)

What happened next has never been disputed. Captain Jim Richardson, a noted Dorchester boat builder in his own right, accompanied Rowe to Wingate. He was the one person that both Rowe and Parks would trust to review the quality of work that had been done on the replica skipjack.

Richardson inspected the work and told Rowe it was good construction. Parks joined them in the boat house and told Rowe to pay him the $1,000 he was owed. Richardson left the boat house and Rowe came out minutes later and asked him if he thought Parks would take $700. Richardson told him no. When Rowe returned to the shop, Richardson saw him reach into his pocket, thinking he was going for his wallet.

“The next thing I heard was as shot and then two more,” Richardson later testified.

Bronza Parks was dead on the floor of the shop, shot twice in the head and once in the chest. Rowe was holding a .38 caliber pistol. He still held the pistol when the sheriff arrived.

Mary Harding says that Richardson’s role has been misreported over time. She said many believed that Richardson brought Rowe to Wingate. “Dad wanted Jim there, he was a friend,” she says. “Orville blamed Jim and never spoke to him again.”

After he was whisked away to the Dorchester jail, the legal process kicked in and Rowe would be held in jails, mental hospitals and state prisons for almost two decades. A month after the shooting he was sent to Spring Grove Mental Hospital where he was found mentally incapable to stand trial.

The case was transferred to Wicomico County because it was feared that the killer of Bronza Parks could not get a fair trial in Dorchester County. The trial didn’t start until February 1963. Rowe’s mental state was the heart of the defense with a stream of psychiatrists giving conflicting testimony.

After a four-day trial, the jury convicted Rowe of second-degree murder, finding that he had been sane when he killed Parks, but he was insane during the trial. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Rowe’s lawyers appealed the verdict and in 1964 the Maryland Court of Appeals overturned the conviction ruling that Rowe should not have been tried if he was insane during the trial as the jury had found. In 1965, seven years after shooting Parks, Rowe was found guilty and sane by a Baltimore jury. Rowe was again sentenced to 18 years, this time with credit for time served.

In the late 1970s, Rowe moved to Catonsville outside of Baltimore and began a vocation as a writer, often sending missives to the Baltimore Sun and other local newspapers. Most of his letters were of a controversial and conservative nature, frequently drawing responses from other letter writers whose ire he had piqued. He contended in one letter that persons who did not comply with their military draft notice should be put in front of a firing squad. His claim that blacks fought for the Confederacy drew heat from readers who challenged him for proof. In a long treatise published in the Washington Times in 1996, Rowe wrote about the history of Confederate flags. He said the current version of the Star and Bars did not exist during the Civil War. At the end of the story he listed himself as “retired.”

Rowe died in relative obscurity in 2002. He was 83.

The life and the legacy of Bronza Parks, the man he killed in cold blood a half century ago, is still being celebrated on the Eastern Shore and in the hearts of wooden boat lovers everywhere.

In southern Dorchester County, rumors still persist about what happened to the replica skipjack Parks was building for Rowe. Everyone agrees it disappeared. J.C. Tolley says some local men took it away and burned it. Snooks Windsor says he knows.

“It was chopped up and buried over there,” he says pointing to a rise of high ground topped by a flag pole just south of his marina.

.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.