In all, Frederick Douglass devoted a total of 41 chapters in his three autobiographies to his childhood and adolescence in Talbot County, in many ways the most pivotal years of his life. Those books helped catapult him to international fame, which in turn made Douglass one of the most recognized and photographed of Americans in the 19th century.

And yet, even today, Douglass’s Talbot County years remain cloaked in mystery and obscurity. Except for a few road markers, a statue in Easton’s Courthouse Square, and a highway that bears his name, little remains to help Americans remember—much less understand—the landscape that left such an indelible mark on one of the greatest of early Americans. It’s as if the county’s soggy soil has gobbled up the memory of those vanished years.

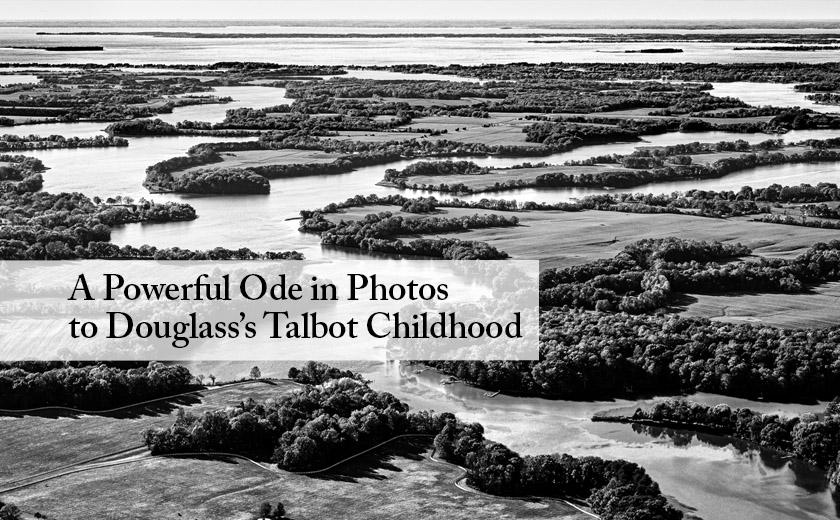

Jeff McGuiness—photographer, writer, St. Michaels resident—has devoted five years of his life to filling that void. In all seasons and all kinds of weather, McGuiness roamed the rivers and fields, the houses and eroding shoreline with one mission in mind: To match selections from Douglass’s own writings with scenes that brought them to life. He sought to capture through his camera lens the watery recesses and farmland where Douglass spent 11 of his first 20 years, starting with his birth in 1818.

The result is a lush, 250-page, large-format book, Bear Me Into Freedom: The Talbot County of Frederick Douglass. The book is an evocative, beautiful, and essential addition to the history and literature of Maryland and the Eastern Shore. Published by the St. Michaels Museum, it is also a testament to the bubbling cultural ferment of the county itself.

Anyone who has spent significant time between the Tuckahoe River and Tilghman Island should know that the region is dotted with the places that formed Douglass as a child and young man. Born enslaved and fatherless along the banks of the Tuckahoe. Sent at age six with his grandmother to the gleaming Wye House plantation on the Wye River. Dispatched to the home of Thomas Auld in St. Michaels after years in Baltimore. Marched off at 15, as a disciplinary action, to a small farm near Whitman, where he had his famous fight with a sadistic enslaver, Edward Covey, near the shores of the Chesapeake. Seized at the age of 18 at the Freeland farm north of St. Michaels over an aborted escape plot and frog marched to the Easton jail.

Of all those events—the tragedies, the heartbreaks, the triumphs—there are precious few remnants or markers. Our country is far from equal in doling out its “Washington Slept Here” signs.

At a time when Talbot County and much of the nation has been embroiled in battles over our past and what monuments to erect and which to tear down, McGuiness celebrates and honors what matters most: The land itself, where momentous things happened, so many now forgotten and washed away.

We fight over symbols and abstractions—that granite statue, now moved to another state, carved with the names of the Talbot Boys, or the accompanying signs people stuck in their yards demanding we “Preserve Talbot History.” But neither the statue nor the signs were in active service of remembering or unearthing our true past. We neglect or let fall into oblivion the places where our weightiest events occurred

McGuiness sets out to right this imbalance and to nudge our eyes back to the land itself. His is not a monument-building or sign-erecting exercise. Instead, McGuiness captures fragments of Douglass’s own past much as Douglass would have experienced them then, in all their haunting brevity.

Douglass’s Talbot County roots have been more than ably accounted for in words. Douglass in his three autobiographies devoted extraordinary attention to his childhood and to his tormented love for Talbot County. In addition, Dickson Preston provided a vivid account in his Young Frederick Douglass: The Maryland Years, while David Blight provided still more detail in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

McGuiness’s premise in assembling and writing his book is simple, as he points out in his preface: “Frederick Douglass cannot be fully understood without a visual representation that accompanies the written.” One suspects Douglass would agree, as the great orator and essayist was himself a fervent proponent of the “mighty power” of photography.

McGuiness acknowledges the delicacy of what he set out to do. The book, he notes, is not intended as “archeological or historical documentation nor is it an attempt at a photographic depiction of the unimaginable horror of enslavement.” Instead, the aim “is to place the events Douglass describes so searingly into a visual context, so that the reader can appreciate the physical environment that gave rise to his literature and oratory, which remain vibrant parts of America’s discussion of race.”

On page after page, McGuiness’s images capture the sadness, the longing and even the joy of Douglass’s own words. All were taken after 2018, and yet they feel like magical windows into the first half of the 19th century. His six-image rendering of the young boy’s pilgrimage to Wye House in 1824 perfectly accompanies the awe and ache of Douglass’s own words.

In a few cases, the faithfulness of the photos to Douglass’s own time comes thanks to the wizardry of our own. The gorgeous shots of Wye House, for instance, are all the purer for the meticulous plucking out of all overhead wires or modern amendments. Similarly, McGuiness features an extraordinary aerial shot of Tilghman Island rid of all contemporary clutter and jutting piers. On many a page, you wish the book was several times larger so you could disappear into the vast horizons.

Bear Me Into Freedom is primarily a photo book, but it also contains just enough historical context to guide the reader through each chapter of Douglass’s young life. Its ample citation of sources at the end also gives the book a scholarly heft. This is a volume made with great care.

Fittingly, the book’s title speaks directly to the omnipresence and potency of the Chesapeake Bay itself. During the dark year he spent on the Covey farm at 15, Douglass would often stand along the shore and look longingly at “the countless number of sails moving off to the mighty ocean.” He saw his best route to freedom being a watery one. “I will take to the water,” he wrote later in his first autobiography. “This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom.”

McGuiness has stepped forward at just the right moment with a cultural gift to both the county and the country. Bear Me Into Freedom brings an immediacy and urgency to Douglass’s early life, and with all the dignity you should expect of such an endeavor. Ours is a raucous, ugly, and disjointed era, increasingly unmoored from taste and truth. McGuiness’s book is the opposite of all that: quiet, meticulous, gorgeous, and respectful to a fault.

Neil King Jr. is a former Wall Street Journal reporter and editor who spent much of the past three years in and around Claiborne. His book about his long walk to New York City, American Ramble: A Walk of Memory and Renewal, will be out in March. He and McGuiness worked together on a piece published in The Talbot Spy in early 2021 examining a forgotten field where Douglass spent a pivotal year of his life in 1834.

Charles E. Yonkers says

Neil King’s article about Jeff McGuiness’s new book is another landmark in the continuing and inspiring saga of Frederick Douglass and our Eastern Shore. I can’t wait to see the final product tomorrow, but I know of Jeff’s now-long and meticulous devotion to this book and of Neil’s supporting collaboration and encouragement. That Neil should write such a glowing review is a well-deserved testament to Jeff and to their mutual contribution to our better understandings of Douglass. We can all take pride in this important new account of how Douglass and Talbot County is something we can all be so proud of. It is a Win for Everyone. Bravo to Neil and Jeff.

J.T. Smith says

I second Charlie Yonkers’s comment and am eager to read and see the McGuiness book about Talbot County’s greatest son.