It’s pure pleasure to view “Earthwork,” an exhibit of handsome, well-crafted works at the Carla Massoni Gallery through May 3. As part of “Art of Stewardship,” Chestertown’s month-long series of exhibits and events, it celebrates the natural world and aims at encouraging the desire to be a good steward of the earth, but the question that looms over the show is “Can such art really make a difference?”

This is not a show of confrontational art, and there’s no gloom and doom environmental rhetoric. Instead, “Earthwork” takes a remarkably positive stance reflecting gallery director Carla Massoni’s feeling that it’s only when you come to love and appreciate something, that you naturally develop a strong desire to nurture and care for it.

Environmental art can range from angry protest art to actively engaged work such as Mel Chin’s use of plants to extract heavy metals from contaminated soil in his “Revival Fields” and Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s installations and performances educating the public about urban waste as artist in residence with the New York City Department of Sanitation. The works in this exhibit fall politely somewhere in between, leaving it a matter of opinion how effective they are in raising environmental awareness.

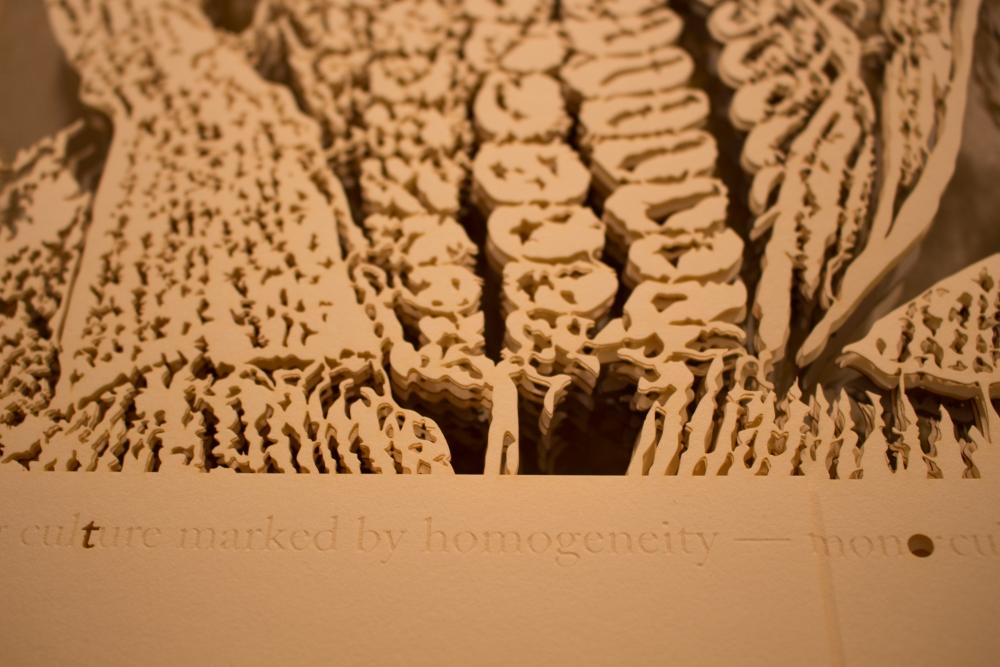

The show’s most specifically issue-oriented piece is Blake Conroy’s “GMO.” An absolute show-stopper, it’s a large, breathtakingly intricate panel of many superimposed layers of laser-cut paper. From a distance, you clearly see an image of ripe ears of corn still on the stalks, but step closer and curious things happen. The image dissolves into a frail web of paper and holes as you realize you’re seeing each layer exactly repeated by the one underneath, just as the genes of genetically modified corn are identical. Just below the corn is an unobtrusive line of text giving the dictionary definition of “monoculture.” From loss of seed diversity and dependence on possibly toxic herbicides to patent issues and the consequences to native species, the implications of GMO monocultures form a large and controversial subject. Leaving viewers to consider its ramifications for themselves, Conroy mischievously points the finger at the main player by highlighting certain letters spaced widely across the line of text. They read: “Monsanto Monsanto.”

Many of the show’s works touch on specific environmental concerns, if only through their titles. Like Conroy’s, some of them presuppose knowledge of these issues. Karen Klinedinst’s quartet of photographs of milkweed pods in sepia tones are striking simply for their achingly beautiful textures and forms, but knowing that milkweed, the host plant of the endangered monarch butterfly, is being largely eradicated from agricultural lands through the use of the herbicide glyphosate, gives them a deep and touching pathos.

Similarly, Rob Glebe’s remarkable large steel sculpture “BeeCause,” while strangely fascinating for the “otherness” of its huge bees at work filling their honeycomb, is really about the pollinator crisis. Animated and alien, Glebe’s bees call to mind old, scary movies like the 1954 film, “Them,” with its giant ants, in a neat allusion to nature out of balance. Considered in terms of the pollinator crisis, the sculpture’s scale gives it a surreal power that points to the magnitude of the problem.

Many of the show’s 21 artists, Glebe included, will be familiar to those who frequent the gallery, but there several artists new to the gallery bring in fresh energy. There’s an effervescent dance running throughout Katherine Allen’s stitched and painted fabric pieces, and the scribbled pencil marks in Susan Hostetler’s “Flock in Funnel Formation” masterfully evoke the dynamic swirl of flocks of blackbirds in flight. A sprinkling of red dots seems a curious addition until you realize they form a spiral, the basic shape of the birds’ path. More rustic than the gallery’s usual fare, Marcia Wolfson Ray’s engaging sculptures made with dried plant materials from marsh elder bushes to hosta leaves explore the delicacy and rhythmic structures of plant growth.

Wolfson Ray’s focus on natural materials is shared by many of the artists giving the show a satisfying feeling of physicality. Vicco von Voss’s burnt black walnut shelf speaks of the natural forces of growth and fire while celebrating the strength and solidity of the wood. Rectangles of richly textured encaustic (pigment suspended in beeswax) give Karen Hubacher’s abstract panels a luscious, earthy feeling, and Carol Talkov’s mosaics, while weak in composition, are captivating for their collections of bits of slate, marble, quartz crystals, pyrite and jasper.

Much of the show’s strength derives from Massoni’s knack for finding relationships between artworks. As is usual for this gallery, the works are hung in such a way that the power of each augments those around it and suggests a wider, more encompassing view. If Michael Kahn’s elegantly serene photograph, “Lilypad Reflection,” with its delicate reflections of clouds in water, was not hung directly above von Voss’s sculptural wall shelf, “Estuary,” you might never notice the nearly identical skim of pale shapes left by a fungus in the grain of the wood.

The ability to sensitize the eye and, by extension, the mind is one of art’s greatest strengths, and this show is intended to do just that. Expanding the concept to the written word, visual images are partnered with evocative poetry in an inspired collaboration between painter Marcy Dunn Ramsey and eco-poet Meredith Davies Hadaway. A stack of copies of Hadaway’s new book, At the Narrows, shares a corner of the gallery with a group of Ramsey’s tiny, intimate gouache waterscapes painted in response to the poems. Their titles are tantalizing snippets of Hadaway’s work that tempt the visitor to read more.

These interactions between works of art are a hint at the premise of this exhibit and of the “Art of Stewardship” project as a whole, that it takes more than individual effort to affect change. Collaboration and the open sharing of ideas are all important to developing sustainable ways to live on this earth. The first stage is to raise awareness; the next is to find solutions to the many challenges to the earth’s well-being. A look at the “Art of Stewardship” schedule of events finds everything from environmentally focused art exhibitions, concerts and storytelling to panel discussions on stewardship issues to community trash cleanups of trails and waterways.

“Art of Stewardship” has become a collaboration between several organizations including the Massoni Gallery, RiverArts, Garfield Centre for the Arts, Washington College, and the Town of Chestertown. It’s a humble, grassroots effort and will need to be duplicated in many other communities, large and small, to make any real difference for the planet earth. Still, it’s a start, and it’s worth noting that it is based on a tried-and-true model of dynamic balance: Nature itself is one big collaboration.

..

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.