There’s some very intriguing photography on view in three of the Academy Art Museum’s four galleries through April 7. A roomful of newly acquired works by such prominent photographers as Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, William Eggleston, Lisette Model, and Bruce Nauman gives a brief taste of the startling breadth of photography’s range over the past century, but it’s the two other galleries, one with John Gossage’s work and the other with Matthew Moore’s, that will really leave you thinking.

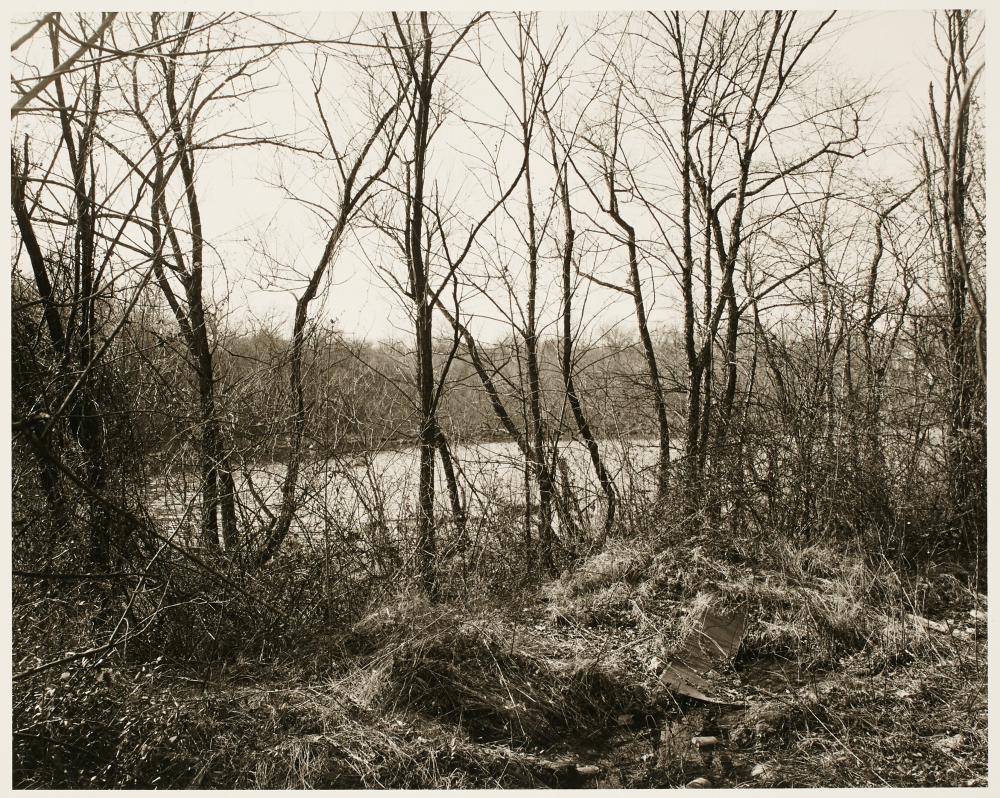

Gossage is a well-known photographer living in Washington who taught at the University of Maryland College Park and who exhibits internationally. On view is “The Pond,” his 1985 series of black-and-white images shot in the vicinity of an unremarkable pond at the edge of a city. Unremarkable is the operative word, because Gossage focuses on its humdrum situation surrounded by ragtag trees, dusty paths and tangled vines bordering on a human landscape of suburban houses and their attendant chain link fences and power wires. A distinctly prosaic tableau is revealed that we know all too well is repeated thousands of times across the country wherever neighborhoods meet natural landscape. There’s nothing of the iconic richness and beauty found in Ansel Adams’s elegant “Cedar Tree and Maple Leaves” just across the hallway. Gossage presents these peripheral landscapes exactly as he finds them, brambled, scraggly, strewn with trash, and mostly overlooked.

But as you peruse these 47 photos (also published as a book), they get under your skin. However unremarkable their setting, they are photographed so skillfully, with such clarity of detail and evenness of tone, that their blandness seems almost exquisite. Every leaf, twig and blade of grass is clearly visible and acknowledged in Gossage’s photographs so that, perversely, they embody both the human longing for nature and our blatant disinterest in its existence. In titling his series “The Pond,” Gossage slyly built in an oblique but nagging reference to Walden Pond and Thoreau’s insatiable curiosity and Transcendentalist awe in exploring its every detail. In Gossage’s landscapes, the human presence is instead one of indifference, conspicuously devoid of any sense of wonder.

Upstairs, Easton photographer Matthew Moore’s “Post-Socialist Landscapes” bear some notable similarities to Gossage’s in that his photographs also draw their impact not from being beautiful, but from the deadpan, black-and-white austerity of their compositions and their crisp and intricate detail. An Associate Professor and Visual Arts Department Chair at Anne Arundel Community College, Moore shares Gossage’s fascination with the human presence in the landscape, but with a focus on how societies use landscape, particularly urban spaces, to manipulate our views of history. This series, shot during a 2014 residency at the Vilnius Academy of Arts’ Nida Art Colony in Lithuania, records the aftermath of Soviet occupation in photographs that fall into three categories.

One explores the crumbling military structures that were used to maintain power. There are former bunkers and machine gun nests being slowly overrun by graffiti and grass. The disused blast berms on Estonia’s Turisalu Missile Base are now so blanketed with small trees and wildflowers that they resemble Bronze Age barrows, transformed into just another bit of history buried in the ground.

A second group records public spaces where statues of Lenin, Stalin or both once stood. In some, the only remaining evidence is a cluster of ornamental bushes or an odd stretch of vacant pavement, while in “Lenin, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2014,” a visible scar still remains in the form of a bare spot smack dab in the center of a plaza. In a shot of Letna Hill in Prague, the huge pedestal that once held a 51-foot-tall statue of Stalin overlooking the city below has been repurposed to support an enormous metronome whose ticking provides a constant reminder of Czech struggles under Soviet communist rule.

In the third category, Moore documents the temporary resting places of these statues. The effect is sometimes comic, as when he discovered a discarded sculpted head of Lenin in a backyard in Estonia between some rubble and a flowering shrub. Others, such as busts of both Lenin and Stalin stored on stacks of wooden pallets, feel far more ominous. Like Prague’s ticking pendulum, they hold a warning that without vigilance, the political pendulum might easily swing back again.

Moore’s work and Gossage’s create a curious dialogue. While Moore explores how we consciously use landscape to promote agendas, Gossage documents what may be an even darker side of human nature—how little we notice or care about how we affect the land. Although both artists can legitimately be termed landscape photographers, their works expose far more about human proclivities than about the landscape we inhabit.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.