Allow time for your visit to “The Moveable Image,” on view at the Academy Art Museum through March 6. Captivating and enigmatic, each of its three video installations will draw you into a different aspect of interrelationship whether personal or with the world at large.

Shala Miller’s video “Mrs. Lovely” is so simple, so spare of means and so powerful, that it will linger in your thoughts for days to come. In the dark window of an antique wooden door, the figure of a black woman begins to appear. First, there’s a soft gleam across her hairline, almost like a crescent moon, then her face and the feminine ruffle at the neck of her dress gradually materialize from the shadows. Life-sized and directly in front of you, it feels like a personal encounter as she begins to speak, hesitatingly musing on the difficult, perhaps dangerous feelings she has for her lover and herself. It’s excruciatingly intimate as if you’re being allowed to venture into her very mind.

In the midst of the Omicron surge, headphones pose a health threat, so the soundtracks of the three installations interfere somewhat with one another. It’s tricky to hear everything Mrs. Lovely is saying, but you can catch enough to understand the ambiguity of her desires and the potential of her latent personal power.

As she speaks, she chews her lip, looks off to the side, sniffs. Her eyes grow wet and the light brushing across her skin reveals it as flawed, a landscape that hints at a history of sadness and tragedy. At one point she declares, “…you know I hate poetry and think it’s the language of the weak,” yet her words, even at their darkest, have the bare honesty and brutal integrity associated with powerful poetry. The very ambiguity of her uncertain words is a kind of revelation into the openness of her search to understand.

While Miller explores the ambiguities experienced in self-identity and personal relationships, the collaborative duo, Collis/Donadio, take on the paradoxical ways we view our physical environment. During the early days of the pandemic, when our towns and cities were eerily quiet, empty of traffic and pedestrians, there was a strange shift in perspective. Instead of constant human activity, the stillness of unlit office buildings, vacant sidewalks and lonely roads prevailed. And there was time to go outside, to watch the wind in the trees and the clouds gliding across the sky.

The built environment looked and felt so different without the usual distractions that nature suddenly took on a powerful presence, shifting our awareness in unexpected ways. Curious about this phenomenon, Shannon Collis and Liz Donadio shot footage of monolithic office buildings, utility equipment, rippling water, wind-blown grasses and trees, and huge cumulous clouds for their video installation “Moving Still.” Projected in geometric patterns onto sculpture plinths and movable walls (standard museum equipment repurposed) as well as the gallery walls behind, they fill the room with an exquisite dance of architecture and nature entwining as partners, the natural movement of water, wind and clouds contrasting with and accentuating the stillness of the manmade environment.

Aptly titled “Moving Still,” both for this contrast and for our slow and cautious movements as we adapt to the continuing effects of the pandemic, this installation is a bit like film noir—mysterious and largely unpeopled. A droning soundtrack layering resonant tones with ambient sounds of passing traffic and children’s voices, just as the images are layered, adds to the aura of familiarity and strangeness.

Gradually, you begin to sort it out. It’s an overlay of windy trees that makes a steel and glass tower seem almost on fire and the angular shadows flashing by at one point are glimpses of the superstructure seen while crossing the Bay Bridge. In a palette limited to shades of gray, white, watery blue, and (like a promise of returning life) a tiny touch of green, small segments of video appear simultaneously in two or three different places setting up repeating rhythms and a certain sense of unity. The effect is mesmerizing. The more you watch, the more you see and the more you are aware of the hugeness of the forces of nature. There’s a sense that, no matter what, their ageless dance continues, Covid or no, and even (in a tacit reference to climate change) with or without our human presence.

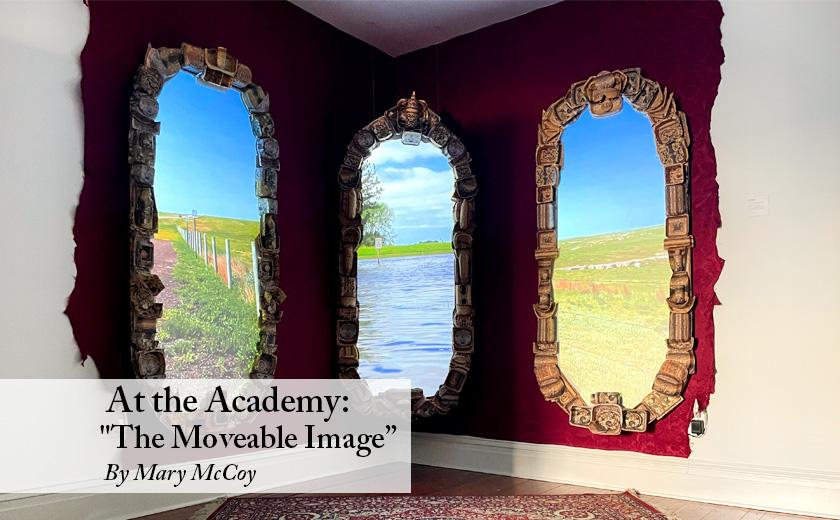

In Rachel Schmidt’s installation “Vanishing Points,” the damaging effects of human presence are repeatedly referenced. Although its three ornate frames resemble fancy full-length mirrors, instead of presenting images of ourselves, they show videos of landscapes.

There’s nothing like an ostentatious gold frame to proclaim that something is art, but in contrast to traditional landscape paintings, her mountains, moors and windblown grassy fields are never picturesque. Interspersed with sequences of rushing flood waters where a road should be, a mountainous landscape scarred by quarrying and closeups of discarded tires, a ruined stone chapel, litter, and a dead fish, an atmosphere of barren desolation prevails. Very occasionally, a person walks through one of the landscapes, but each one of them is digitally altered in some way, set apart from the scene as if humans don’t actually belong there.

Schmidt’s message continues to unfold when you realize the gilded frames are fakes, constructed of dozens of discarded bottles and carryout trays sheathed in printouts of closeups of the pretentious frames they mimic. It’s a comic but stinging comment on our throwaway society but even more significantly, on our penchant for trying to make things look good even if it’s only a surface impression.

This theme crops up again as the camera pans across a wooded hillside where clothing is tied on every available tree. The scene is not explained, but intuition is enough to suggest some kind of ritual activity. Clothing is like the frames—it’s meant to make a certain impression, to convey a hoped for self-identity. So to leave articles of clothing in a forest is to offer something of ourselves to nature, whether as a gift or a request. To give a little background, this is the site of a sacred spring (not shown in the videos) at Black Isle on the northeast coast of Scotland. It’s one of many centuries-old holy or healing wells in the British Isles and Ireland where people come to dip a piece of clothing in the water, say a prayer for healing, and hang the cloth in a nearby bush or tree to weather away, presumably taking the illness with it.

Curiously, the number of visitors to these pilgrimage sites has increased exponentially in recent years, as has the amount of clothing and other objects they leave. The result is an appalling mess, but it’s also indicative of our largely suppressed need to connect with nature, a kind of plea for help for something beyond the human world to save us.

There’s an innate wisdom in the urge to seek interrelationship, to understand how we fit into this complex and contradictory world. Through their work, these artists suggest that it is only through diligent self-reflection that we can open our minds and vision to our situations, whether personal or environmental, in order to live fully and wisely.

Mary McCoy is an artist and writer who has the good fortune to live beside an old steamboat wharf on the Chester River. She is a former art critic for the Washington Post and several art publications. She enjoys kayaking the river and walking her family farm where she collects ideas and materials for her writing and for the environmental art she creates, often in collaboration with her husband Howard. They have exhibited their work in the U.S., Ireland, Wales and New Zealand.

MaryLou Armstrong-Peters says

What a stunningly beautiful review! Nature and humanity are so intertwined; this show speaks deeply to the inner heart and Mrs, McCoy’s review has captured that deep relationship that the videos depict perfectly.