Today the town of Oxford in Maryland is often referred to as a tourist attraction for its waterfront location, quiet charm, maritime activities, and hosting the oldest privately-operated ferry service still in use. If you Google the town’s history, you’ll find consistent information on how fortunes were made and lost throughout the centuries.

It usually recounts how the demand for tobacco in the 17th and 18th – century, dried up when America won its independence from Britain. There are detailed discussions about how after the completion of the railroad and improved packing and canning methods in the 1870s, oyster and crab harvesting again brought prosperity to the town. Once over-fishing and marine diseases destroyed the industry in the early part of the 20th century, Oxford witnessed the closing of packing houses and smaller local businesses. After the railway and steamships disappeared, Oxford became a quiet little town populated mainly by watermen, until it’s recent resurgence as a vacation draw.

That’s it.

That recounting of the past is incomplete, however. Nowhere is there mention of the contribution and role of Black people in Oxford’s growth and success. Given the history of America, this omission is remarkable. Here are the missing pieces of Oxford’s past:

The tobacco industry boom created a demand for the slave trade to such an extent that by 1755, Black slaves made up 40% of Maryland’s population. When the tobacco trade ended, the Eastern Shore had less need for slaves forcing their sale to rice and cotton plantations in the South. Some enslaved people fled the area via the underground railroad, while others were released or bought their freedom and started new lives in the county as farmers and laborers.

What is also not mentioned is that Oxford’s revival over a century later drew free Black men and women to move to the Eastern Shore to work on the water or in one of Oxford’s nine packing houses. Their efforts led to the worldwide recognition of Chesapeake seafood, while also building a large and vibrant Black community in the town.

But even that is not the full story. There is so much more that Stuart Parnes, past president of Oxford Museum, wants you to know about the impact the Black community has had. The following is part of “Black Lives in Oxford,” a new window exhibit he curated at the Museum:

“At the turn of the 20th century, nearly 50 percent of Oxford’s population consisted of free Blacks. Most Black families lived in segregated neighborhoods centered along Tilghman, Factory, Mill, Norton, Stewart, Bank, and Market Streets. They gathered at their own social clubs, supported their own shops and trades, prayed in their own churches, and sent their children to all-Black elementary schools.

By the end of WWII, however, Oxford was becoming a remarkably integrated community with very strong relationships between Black and white families. By 1970 after the packing houses closed, there were few economic opportunities left for younger Black people. Many departed Talbot County for Baltimore or Philadelphia, leaving their parents and grandparents to live out their lives in Oxford.

As Oxford’s older generations passed away, much of the rich heritage of our community—Black and white—disappeared with them. Only a few Black families remain in Oxford today, but the importance of their contribution to the history and culture of our community should never be forgotten. These lives mattered in the past, and they still do today.”

The Spy recently spoke to Parnes, Paula Bell, past president of the John Wesley Church, and Ferne Banks, who has been involved in obtaining information for the exhibit.

“This effort,” says Parnes, “actually goes back to Paula’s work with the John Wesley Church in getting the building restored and preserved and in the collection of all of the stories, some of them a series of oral histories done by some of the church elders, that went along with it. The Museum, over the years, had collected very little. So, we needed to go out and start from scratch. And fortunately, all the work that the John Wesley gang did provided a running start because they had made all these contacts and they had collected all these stories, and it was really good.”

One of the important things was to tell the stories of the black members of the Oxford community,” said Bell. “The Church goes way back to 1838, but since my time, I had never seen any representation or exhibit, and this is a community that had long time roots. Stuart was very receptive when I approached him to do this. And with his knowledge, creativity, and background in museum exhibits, it was a perfect opportunity for that to happen.”

So, they gathered a group of people, initially from the Church, and then others who had a connection to the town through their parents and grandparents, and walked around Oxford identifying who lived in all the houses in the black neighborhoods during the 40s, 50s, and 60s. They collected stories, photographs, and artifacts.

That was just the beginning of plans that included utilizing the Cook Shop building at John Wesley, which currently houses the Church’s documentary photography and oral history transcriptions. Both the space and location were perfect for an extensive museum exhibit primarily since it’s located by Screamersville Rd, an area which was also, at one time, a large Black community.

Said Bell: “My personal vision is for it to be turned into a real museum with proper lighting and proper flooring insulation. It really needs to be structurally sound so that whatever goes in there is protected.”

But all that is expensive. It didn’t help that a pandemic happened as plans were being discussed. Luckily, that didn’t stop the visionaries.

“I didn’t want to wait any longer,” said Parnes, “especially with all that is going on right now in this country, recognizing the contribution of Black people. Something had to be done now; this isn’t unique to Oxford. The window display is meant to be just a start; there’s so much more to do.”

There is also so much more to learn, whether you live in Oxford or not.

“I’m a newcomer,” explained Parnes. “I’ve only been here for 15 years. But I’m a history guy and very aware that you should learn about the place where you’re living. There are new people in town who come from other places, and we haven’t tried very hard to really tell them about their homes. How did it get to be the way it is, why does it look the way it does, and who lived in all these places? Why are there real fancy streets and others that aren’t so fancy? You have to understand a bit about the heritage to know that a lot of Black people that built this town worked in all the businesses that made people wealthy. It’s an important piece of the story for somebody who’s coming to Oxford.”

Fern Banks is part of that history. Her father, Bobby Banks, was a police officer from 1965 to 1978. He was on the John Wesley board, and Banks Street in Oxford is named after him. His daughter recalls growing up in the town where relationships between blacks and whites were not unusual. “The black kids and the white kids at the formerly ‘white’ Oxford school (now Oxford Community Center) got along. We played together, and my first best friend was white. She and I are still friends today.”

Banks’ involvement in this project is invaluable, agree both Parnes and Bell. She has the memories of going to the black schools, the integrated schools, and the churches, and she has the connections to current and former members of the Black community. To Banks, the involvement is also very personal. “Members of my family are buried on a lot off of Almshouse Road. It used to belong to the Brooks family, and when they all died, the lot was sold, and I was down there with the new owner who didn’t realize people were buried back there.”

It is stories like these that illustrate the urgency of this project. Today, Oxford has a population of just under 650, with 90% identifying as white.

“Fifteen years ago,” says Parnes, “all of our neighbors were Black, and none of them are left. We got to know them for a few years, and then they were all gone. And part of what’s happening in Oxford, like everywhere else, is that the town is becoming more and more gentrified. We’re losing all these senior members of the community, and we’re not gathering up their stories.”

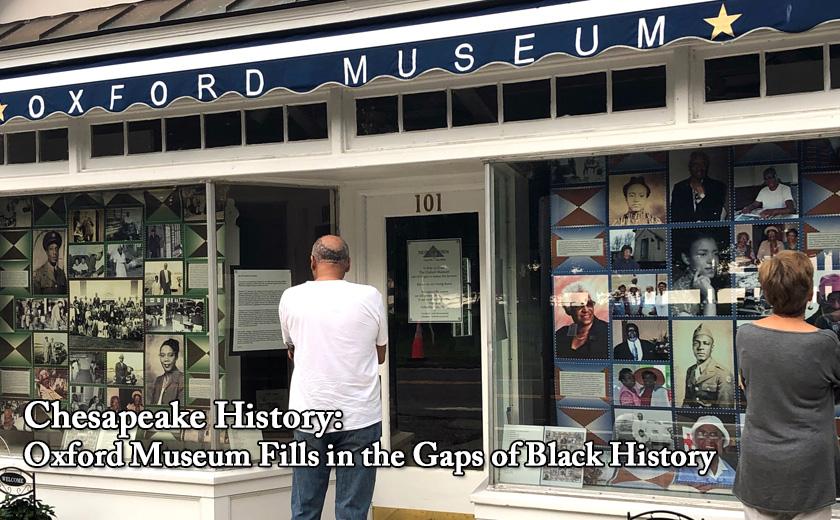

So, for now, while Oxford Museum is closed, the “Black Lives in Oxford” display is two windows that contain a reproduction on a banner of the faces of people who used to live in the town, along with short transcriptions of the interviews they do have. Parnes hopes the Museum will reopen soon, and the original artifacts and photographs can be appropriately displayed. They even envision a walking tour in Oxford, with stops along the way that tell the residents’ stories.

“This is long overdue,” says Parnes. “It’s not always a pleasant story, but it’s half the story of Oxford, and we have to tell it.”

The Oxford Museum, located at 101 S Morris St, Oxford, is looking for stories, art, photographs, family records, and artifact pertaining to this exhibit. “Black Lives in Oxford” will be on display through the fall.

Val Cavalheri is a recent transplant to the Eastern Shore, having lived in Northern Virginia for the past 20 years. She’s been a writer, editor and professional photographer for various publications, including the Washington Post.

Vickie Wilson says

Thanks for sharing this great history

Mary Margaret Revell Goodwin says

I am so incredibly proud of the Oxford Museum for this exhibit! We here at the Maryland Museum of Women’s History have developed such a great relationship for this museum. We too are in the process of developing our own exhibit of some of those who were enslaved and involved in the making of the greatness of some of the plantations in Queen Anne’s County. To such a major extent the contribution of the historic enslaved communities and those emancipated has been ignored, lost, forgotten–pick any or in fact all of the adjectives. What the Oxford Museum has done is the beginning of an effort that so totally deserves and must continue through these next few years. SO many families in the Black Community have contributed to the way of life and the economy on the Eastern Shore, and without recognition! This is a great first step to make the work they did known to all. I know all the individuals in this project and I applaud them and salute them for the incredible efforts they made to make this presentation happen! And thanks to Val Cavalheri for bringing this story to the Spy and the Spy for promoting it! We are all grateful for this story.

Janet Rogerson says

So interesting. I live in Scotland and have visited your museum a couple of times;Indeed I learned Scottish history when I saw the people who came on a ship were captured Scots!!

Would it be possible to have slides of artifacts from the window displayed electronically ? I live walking around Oxford and your idea of a walking historical tour or leaflet is a great idea. I hope to visit again in thefuture

Julie Wells says

I will see what I can do. Please email the museum with your email. Thank you

Oxford Museum

Teresa Greene says

Thank you so much for this article.

As a member of John Wesley Preservation Society, it is nice to see the very hard work of a lot of people, who started this journey about 17 years ago, begin to take shape. Thank you Kathy Radcliff, rest in heavenly peace Hollis, Bobby & Doretha Raisin, knowing that what you started all those years ago, will continue on. WE GOT THIS!! And will continue to make you proud as we do the GOOD work that you began. GREATER THINGS ARE COMING!!

Teresa

Paula Bell says

Many thanks to Val for her article which shared the history of this important Museum project. It should be noted that Kathleen Radcliffe, as well if the members of the original John Wesley Board, were responsible for the restoration of the church. They worked tirelessly over a 12 year period to preserve the buildings and the property associated with their heritage. It should also be noted that the interviews from which some of the exhibit material was derived were conducted by Kathleen Radcliffe, Elaine Eff, and Dr. Clara Small.

The members of the current board, as well as, members of Waters Church were delighted to collaborate with the Oxford Museum to bring the exhibit to fruition. Thanks to Julie Wells, the current Oxford Museum President, for all her support and Stuart Parnes without whom this would never have happened.

Paula Bell

Paula Taylor says

I took the afternoon to drive to Oxford with my Mom (Joyce Taylor), son & granddaughter. I read about the display and told my Mother who was raised in Oxford.

She enjoyed looking at the pictures, naming the people she remembered and seeing her family especially her Dad (James Taylor) the infamous Dock Master. I also was surprised to see a younger picture of my Mom who my son says looked like a younger version of me. I enjoyed the whole experience & driving through the streets where I spent a lot of my own childhood. Well done by all those involved!

Denise Willis Husband says

Live this story born and raised there a lot of history there glad it is finally recognized