The art world went through major changes at the beginning of the 20th Century, as did the world at large. European artists were moving far from the classical traditions of the past 500 years (1400-1899). Absolute representation of the world was no longer the goal of the new Paris avant-garde. Picasso led artists into the direction of Cubism, inspired by the geometry of the then available African sculpture. Matisse started the expressionistic style of Fauvism, inspired by the flowing lines of Art Nouveau and an emotional attachment to strong colors inspired by van Gogh, Gauguin, and Munch. The Japanese woodcut had inspired a relaxation of the traditional rules of perspective.

This new wave of art and artists also had a strong presence in Germany. Franz Marc (1880-1916), a native of Munich, was one of the prominent artists arising in Germany. The son of a minor landscape painter, Marc began to paint early in his life. After fulfilling his military service, he studied art at the Munich Academy of Fine Art from 1900 until1902. Unsatisfied with the traditional realism being taught, he went to Paris in 1903, and for the first time saw Japanese woodcuts. Returning to Paris in 1907, he discovered the strong color palettes of Gauguin, van Gogh, and Matisse, and the new Cubist work of Picasso and Delaunay. Marc wrote in 1908, ‘’I am trying to heighten my sense of the organic rhythm that beats in all things, to develop a pantheistic sympathy with the shivering and flow of blood in nature, in trees, in animals, in the air…I am trying to make a picture from it with new movement and with colors which are a mockery of the old kings of studio pictures.”

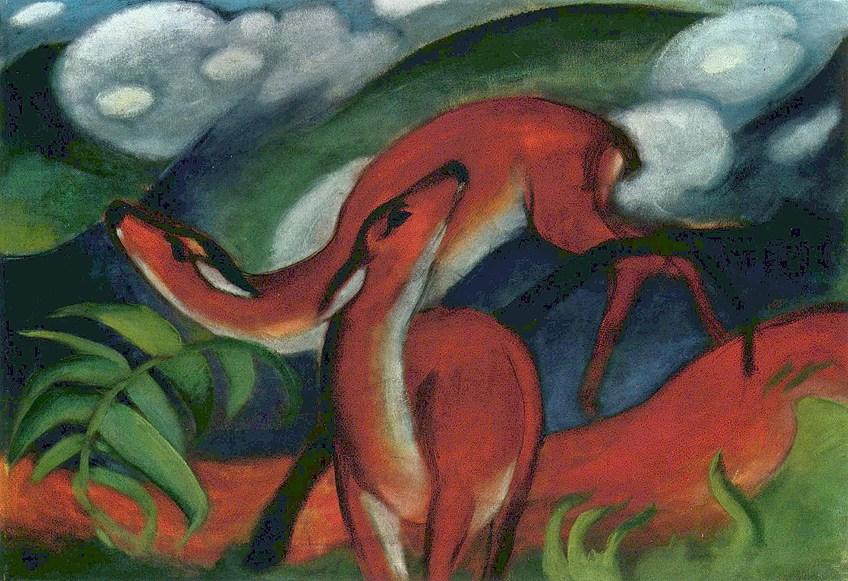

Marc’s interest in painting animals began early. He supported himself by giving animal anatomy lessons from 1904 until 1910. His painted series of horses, cows and bulls, dogs, foxes, and deer which he studied from life and at the zoo. “Red Deer” (1912) (39’’x 27’’) is an example of his moving away from realism to find what he described as “the inner mystical construction of the world.” Marc thought that animals represented the innocence lost by man, and that animals were one with the rhythm of nature. In this painting, the sweeping curves of the “Red Deer” are applied equally to the deer and the landscape. The clouds, mountains, paths, and plants are integrated into a symbiotic relationship with the deer. The beauty, strength, and grace of nature is revealed.

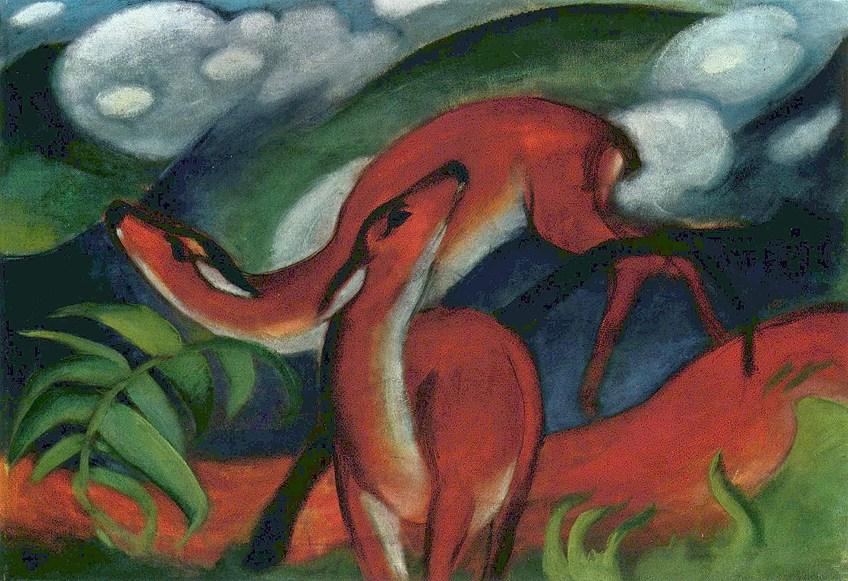

“Deer in the Forest” (1913) (40” x41”) (Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.) expresses Marc’s concept of what a painting should depict: “I can paint a picture: ‘The Deer.’ However, I may also wish to paint a picture ‘The Deer Feels.’ How infinitely more delicate the artist’s sensibilities must be to paint that.” Four brown deer nestle together in the forest, while a fifth curls up nearby. The trees surround them and provide shelter. Marc has composed the four deer in a triangle, the most stable composition artists have used for centuries. The surrounding environment is composed of geometrical Cubist shapes.

A solitary bird flies over, and like the deer, seems undisturbed by a glowing red behind it and the black swirls that suggest a coming storm. Questioning the state of the world in which he lived, Marc asked, “must they (paintings) not be full of wires and tension. Of the effects of modern lights, of the spirit of chemical analysis which beaks forces apart and arbitrarily joins them together?” Very much aware of the new scientific discoveries of Rutherford in1911, the study of the atom, Marc’s reaction was immediate “Today we dissect nature, which is always illusory, and put it back together again in accordance with our will. We see through matter. Matter is something which man today can tolerate at most; he cannot acknowledge it.” Marc’s colleague Kandinsky stated; “The crumbling of the atom was to my soul like the crumbling of the whole world. Suddenly the heaviest walls toppled. Everything became uncertain, tottering and weak.”

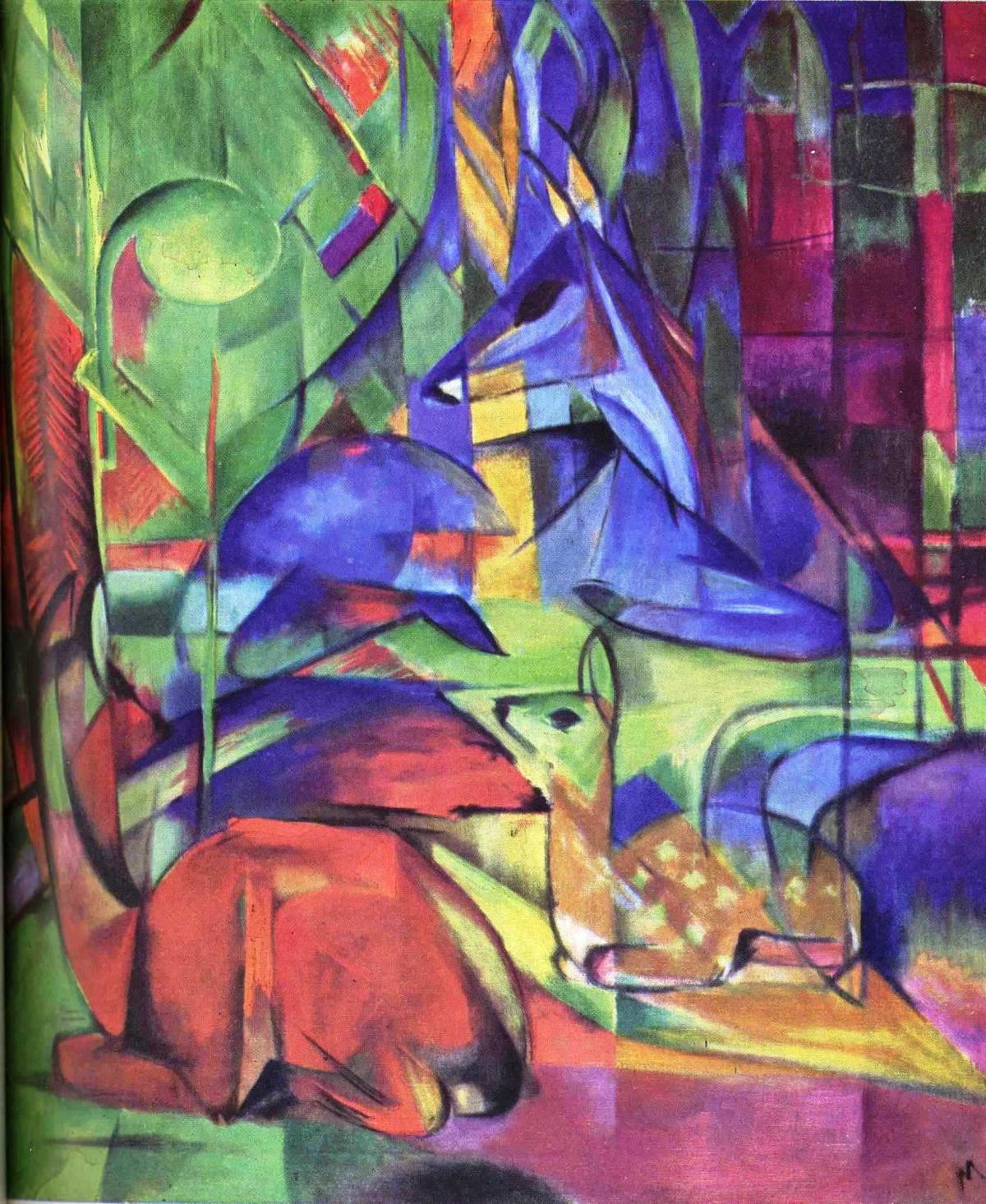

“Animal Fates” (1913) (6’5’’ x 8’10’’) is extremely large and takes a different direction from most of Marc’s paintings. The animals are in extreme danger. The composition is crisscrossed with slashing forms in red, black, and dark blue. The forest is burning, and a large tree trunk falls diagonally across the composition.

Marc’s choices of colors were intentional. He describes his theory in detail: “Blue is the male principle, severe and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, cheerful and sensual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy, the color that has to come into conflict with, and succumbs to the other two…But then if you mix blue and yellow to make green, you rouse red, matter the earth, but here, as painter, I always sense a difference: it is never possible altogether to subdue eternal matter.”

The two powerful green horses at the upper left of the painting symbolize power, referring to the horsepower of engines. They are caught in the burning red forest. The horse on the left cries out in agony. At the lower left, two red boars symbolize ferocious male strength but are subsumed by the fire. The central figure of the composition is a blue male deer. His exaggerated posture, neck thrown back parallel with the falling tree trunk, illustrates his fear and imminent death. The red tree trunk will surely crush him. At the middle right, four reddish-brown deer, their noses all pointed into the forest, are perhaps the only possible survivors. Marc, along with many, anticipated the conflagration of World War I. On the back of the canvas Marc wrote, ”and all being is flaming, suffering.”

Marc and Kandinsky were founding members of the Blue Rider group in Munich in 1911. Both loved horses and the color blue, thus the name of the group. They also agreed on many philosophical points. They believed in the symbolism of colors. Marc expressed their view: “Namely the one great truth is that there is not great pure art without religion, that the more religious art has been the more artistic it has been.” The purpose of the group was not only to mount art exhibitions but also to introduce the proletariat to new ideas. The first Blue Rider Almanac (1912) contained woodcuts and announced the artists’ purpose “to create forms which could take their place on the altars of the future intellectual religion.” Kandinsky’s book On the Spiritual in Art (1912) has never gone out of publication.

“Deer in the Forest” (1913-14) (43’’ X 39’’) clearly represents the idea of spiritual. It does not refer to a religion, but that art had the power to evoke inner emotions and feelings. The composition is made up of three deer, all lying comfortably and at peace. The top most deer is the blue male. His body stretches from side to side of the composition as to protect the other two deer. At the left, the doe, composed of green, yellow and reddish brown, looks toward the male. Between the two is the faun. Marc has chosen the natural camouflage coloring of a faun, with some of the forest colors, light spring green and blue, to integrate the faun into the setting.

The light green shape at the upper left of the composition resembles the new growth of a plant. At the right, balanced against the plant, is a rich array of purples. From the top center, a yellow stripe representing sunlight enters the scene. The introduction of square shapes and black outlines were intended to remind the viewer of the leaded glass in church windows.

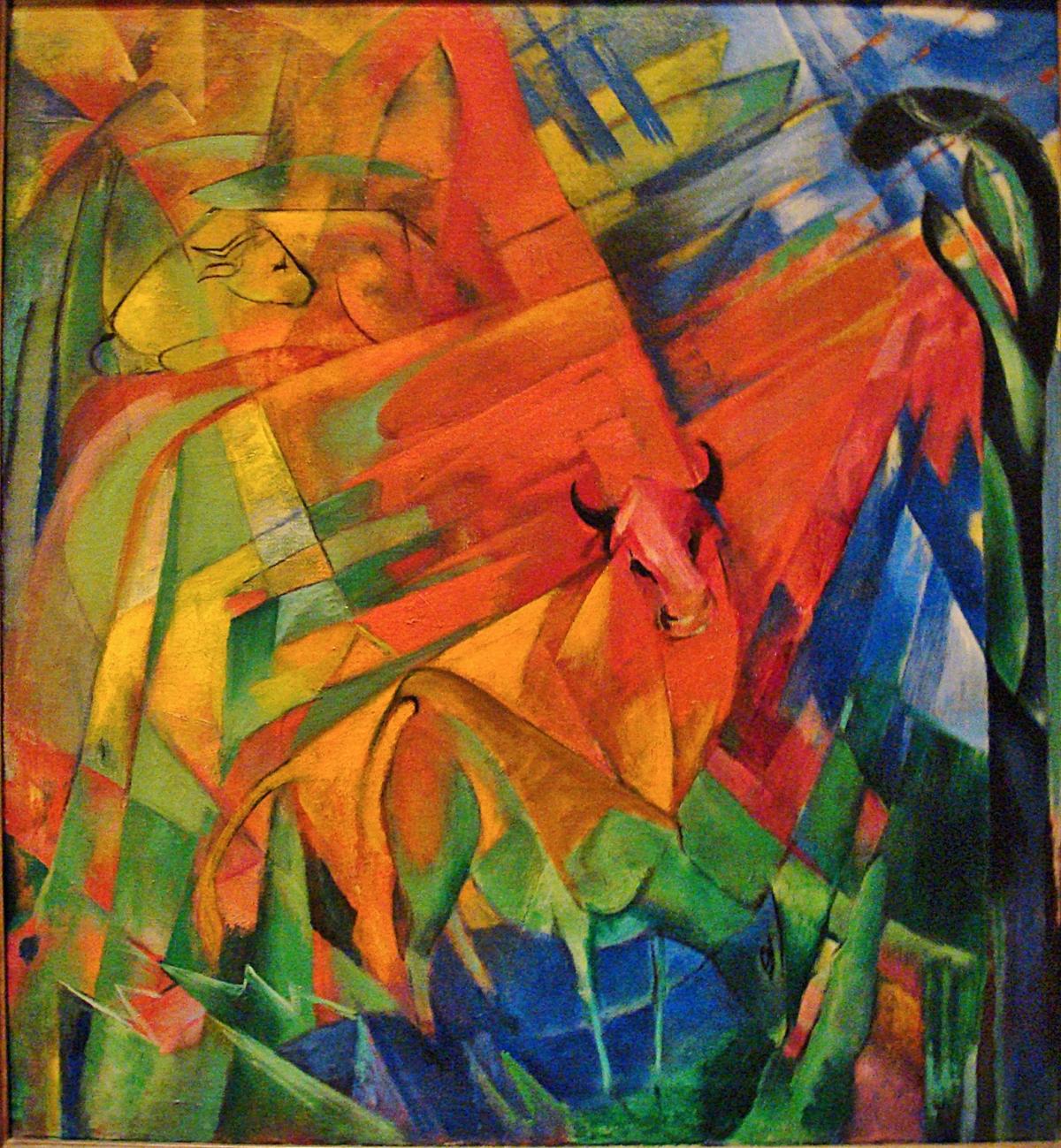

As World War I approached, Marc’s paintings began to show his apprehension and fear. In “Animals in a Landscape” (1914) (43’’x 39’’) powerful red takes control of the composition. Placed within the red is a large bull with black horns. His head is pointed in the direction of a yellow deer, partially integrated into the green forest, her front legs in the blue water. She does not yet feel the wrath of the red. At the upper left, a yellow cow rests peacefully, still unaware of the red danger moving in her direction. Tall black serpents command the right edge of the painting. The red menace emanates from the serpents, and it is in position to sweep over all in the painting.

In his last paintings, Marc began to see an ugliness in nature he had thought existed only in humans, and he expressed his disgust with the modern world. For a short time, his paintings were abstract. He served in WWI as a cavalry officer, and he was put to work camouflaging artillery. His respect and love for nature returned, and in a letter to his wife in 1915 he wrote, “People with their lack of piety, especially men, never touched my true feelings. But animals with their virginal sense of life awakened all that was good in me.” Unfortunately, Marc was sent to the front and died at the battle of Verdun on March 4, 1916. The order to withdraw him from the front and from combat because he was a notable artist came a few days later. Beside his body was his sketchbook” Magic Moments, Plant Life Coming into Creation.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.