Henri Julien Félix Rousseau (1844-1910) was a famous French painter of the Naïve style. A graduate of Laval High school, he was an average student, but he won some drawing and art prizes. He served in the army beginning in 1863, and then he moved to Paris in1868 to support his mother after the death of his father. He became a customs agent in 1871, and held that position until he took early retirement in 1893. He drew and painted as a hobby until his retirement.

“Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprise!)” (1891)

Rousseau began exhibiting his paintings annually at the Salon des Independents, organized in Paris on July 29,1884, in opposition to the formal French Academy. The slogan was “without jury nor rewards.”

“Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprise!)” (1891) (51”x64”) is the first jungle scene Rousseau painted. He was inspired by paintings he had seen in the Louvre, exhibitions at the 1889 and 1900 World’s Fairs in Paris, and illustrations in children’s books, magazines, taxidermy, and the Botanical Gardens in Paris. Rousseau was self-taught, the definition of a naïve painter.

The leaping tiger–teeth bared, claws out–focuses on prey that is outside the painting. Rousseau once said the tiger was going to pounce on a group of explorers. Even without the prey, the tiger is ferocious. It leaps through a richly colored jungle of long leaved plants, grasses, and trees with every kind of leaf, and in a rainstorm. To create the rainstorm, Rousseau painted a series of silver streaks running from left to right throughout the scene, the same direction of the tiger’s charge. The composition is held within the canvas by the large, dark green leafed plant at the lower right. “Surprise!” was Rousseau’s original title.

The painter Felix Vallotton commented, ’’…the tiger surprising its prey is a ‘must-see’; it’s the alpha and omega of painting and so disconcerting that, before so much competency and childish naïveté, the most deeply rooted convictions are held up and questioned.”

“War” (La Guerre) (1894)

Rousseau served in the army for four years, and he lived through two traumatic wars, the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) and the Siege of Paris (1871). “War” (La Guerre) (1894) (45”x77”) was described in the 1894 catalogue of the Independents: “War; she passes terrifyingly, leaving despair, tears, ruin all around.” Riding side-saddle on a black horse, War charges through the scene. Her hair in wild spikes, she holds a sword in one hand and a flaming torch in the other. Her white dress, usually a symbol of virginity and innocence, is tattered at the hem. The galloping black horse has a spikey mane and tail. Black tree branches crisscross the blue sky. The clouds range in color from yellow to red.

The gray and brown earth is strewn with corpses. Some are naked, some clothed, and there are amputated limbs. Black crows pick at the dead bodies. Rousseau’s style in naïve. His figures and landscape are poorly painted, clearly not up to realistic Academy standards. However, this painting is neither simple nor unsophisticated with respect to its message.

“The Sleeping Gypsy” (La Bohemienne Endormie) (1897)

Rousseau challenged himself with many themes. “The Sleeping Gypsy” (La Bohemienne Endormie) (1897) (51”x79’’) (MOMA, N.Y.) illustrates his interest in North Africa. Although he was self-trained, he grew as an artist, developing greater technical skills. The painting appears to be simple, but in fact the composition is complex. The gypsy woman, asleep in the desert, wears a colorful robe of horizontal stripes. Her hair is covered with a shawl, also painted in stripes. Her head rests on a striped pillow.

A walking stick and a lute are placed beside her. The horizontal strings of the lute stand out against the wood, while an orange circle surrounds the sound hole. The placement of the white full moon balances the white body of the lute. The white strings of the lute stand out against the black neck, and the fret board bends at a diagonal. The angle of the fretboard repeats the angle of the gypsy’s arm. A tall orange jug, the vertical stripes of the pillow, and the artist’s signature complete the right corner.

Standing behind the sleeping gypsy is a magnificent lion. Its mane, painted a soft gold color, flows in small ripples from its back to its head. The white color of the eye repeats the shape and color of the moon and the lute. The lion’s front legs are straight and its back legs are bent in the normal position. The position of the gypsy’s feet repeats the diagonal design, but in the opposite direction. Her toenails stand out against her dark skin like the pegs on the fretboard. The lion’s tail curves upward and ends in a vertical tuft. The painting is a complex and interesting composition of verticals and horizontals.

“View of Sevres Bridge and the Hills of Clamant, Saint Cloud and Bellevue with Biplane, Balloon, and Dirigible’’ (1908)

“View of Sevres Bridge and the Hills of Clamant, Saint Cloud and Bellevue with Biplane, Balloon, and Dirigible’’ (1908) (32’’x39’’) is one of Rousseau’s landscape paintings of Paris and its environs. The inclusion of the three air ships, a biplane, balloon, and dirigible, is unusual, but represents Rousseau’s knowledge and interest in new inventions and current events.

Rousseau found favor with the avant-garde artists of Paris and with a solid buying clientele. Picasso saw a Rousseau canvas for sale on the street, intended to be sold to a young artist to paint over, and immediately went to meet him. Picasso then held Le Banquet Rousseau described by American poet and literary critic John Malcolm Brinnin as “one of the most notable social events of the twentieth century. It was neither an orgiastic occasion nor even an opulent one. Its subsequent fame grew from the fact that it was a colorful happening within a revolutionary art movement at a point of that movement’s earliest success, and from the fact that it was attended by individuals whose separate influences radiated like spokes of creative light across the art world for generations.”

Among those celebrating Rousseau at Picasso’s party were Fernande Olivier, Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin, Constantine Brancusi, George Braque, Daniel Kahnweiler, and Leo and Gertrude Stein, the crème de la crème of the avant-garde. The 64-year-old Rousseau was the friend of, accepted and admired by, and influenced many of the new artists of the 20th Century.

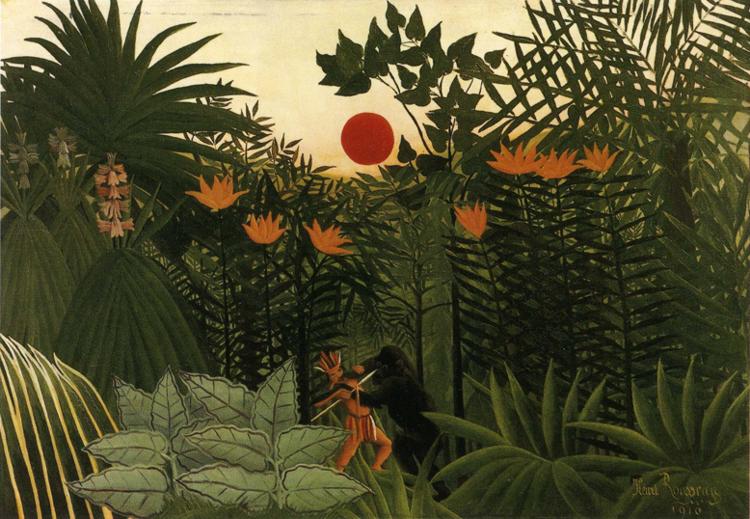

“Tropical Landscape: An American Indian Struggling with a Gorilla” (1910)

Rousseau is most famous for his jungle paintings, but he did not return to them for seven years after his first success. “Tropical Landscape: An American Indian Struggling with a Gorilla” (1910) (45’’x64’’) (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond) demonstrates his unique ability to combine the new and the old. Rousseau never traveled farther than Paris and nearby towns, but his imagination was unlimited. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show played in Paris in 1889. Indians were in the show, but they did not fight gorillas in the jungle. His jungle paintings include both Botanical Garden species and common house plants. Rousseau stated, “Nothing makes me so happy as to observe nature and to paint what I see.”

“The Dream” (1910)

“The Dream” (1910) (81”x108’’) (MOMA, N.Y.) is one of Rousseau’s most celebrated paintings: “When I go into the glass houses and I see the strange plants of exotic lands, it seems to me that I enter into a dream.”

The jungle is teaming with animals and bright flowers. A gray bird has settled among the dark leaves, three brown monkeys are perched in the trees, an elephant’s head and trunk are obscured by leaves, an orange crested bird sits on a tree full of oranges, and two golden lions peer through the ferns. An African native plays a flute. Music was another of Rousseau’s great loves. He won prizes in music and art in high school. He played the violin in the streets to supplement his income until his art provided income to cover the cost of supporting his family. Although he did not paint musicians often, his work might be said to have a lyrical, musical quality. He said, “This woman asleep on the couch is dreaming she has been transported into a forest listening to the sound from the instrument of the enchanter.”

In “The Dream,” the nude reclines on a dark red velvet couch with a carved wooden back. Her long brown hair flows over her body. She is buxom and curvy, but far from the reclining nudes of Titian, Rubens, or Ingres. The whole painting radiates innocence, simplicity, and charm. Art critic Thadee Natanson commented in 1897, “Mention must be made of Monsieur Henri Rousseau, whose determined naiveté manages to become a style…with ingenuous and stubborn simplicity.”

Rousseau suffered from an inflammatory necrosis in his leg, turning into gangrene, and he died of a blood clot on September 2,1910. His funeral was attended by seven of his great friends, including Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Paul Signac, Apollinaire, and Brancusi, who composed the epitaph for his tomb stone;

We salute you Gentle Rousseau you can hear us.

Delaunay, his wife, Monsieur Queval and myself.

Let our luggage pass duty free through the gates of heaven.

We will bring you brushes paints and canvas.

That you may spend your sacred leisure in the

light and Truth of Painting.

As you once did my portrait facing the stars, lion, and the gypsy.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Jennifer Martella says

Beverly,

I have been a huge fan of Rousseau since I first saw his enchanting work at the Met. I have a print of The Dream in my bedroom and ThevSleepibg Gypsy has joined my growing collection of art magnets on my fridge.

Thank you ao much for this!