The musical setting of the carol “Deck the Halls with Boughs of Holly” was first mentioned to have been played by a Welsh harpist for New Year’s Eve in the1700’s. The lyrics were added in 1862 by the Scots musician Thomas Oliphant. Holly is the birth flower for those born in December. Although it is now January, the holly’s powers are good inside the house until Twelth-Night, January 6. The qualities of holly last all year outdoors. It is a symbol of fertility, eternal life, strength, good fortune, and goodwill. These qualities all relate to observations of holly trees that survive the cold of winter and last through the summer. A significant number of magnificent tall green hollies can be seen on walks around Chestertown

“The Holly Cart” (1855-1882) (20’’x24’’) was painted by Charles Edward Barnes, a London painter known for his small domestic scenes, especially those including children. He exhibited at the Royal Academy, the British Institute, and the Royal Society of British Artists. “The Holly Cart” is set in a snowy English village where people are gathered to purchase holly from a vendor. A donkey pulls the cart, and a small boy at the left calls out that holly is for sale. Another boy kneels in the snow, binding holly to be carried home. A girl holds holly in her shawl, while an older boy behind her hunches over in the cold.

The display of holly branches in the winter is an ancient practice. Druids believed holly had the power to guard against evil spirits and bad luck. A crown of holly was worn for good luck by Celtic chieftains (Holly Kings). In Celtic mythology, holly trees ruled the dark winter months because they were green and strong, and the red berries were symbols of fertility. The Victorians started decorating with holly indoors.

“Woman Standing in Snow Holding Holly” (1897) is by American artist Edward Percy Moran (1862-1935). Moran trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia and at the National Academy of Design in New York. He is known mostly for his paintings of American history. The painting, also referred to as “Puritan Woman Holding Holly,” is not a portrait. Moran portrays idealized beauty, a “pin-up” popular at the time. The rosy cheeked young woman wears a plain gown with a large white collar and a bonnet, often associated with the Puritans. However, he has painted the fabrics with a shiny satin finish, not humble homespun.

Holly has been a Christian symbol for centuries. The sharp pointed leaves of the holly are associated with the Crown of Thorns, and the red berries were symbols of Christ’s blood. Holly appears in literature and song. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c.1370-1390), a colossal creature that stunned them “was bright green” with no weapon “but in one hand a solitary branch of holly that shows greenest when all the groves are leafless.” “Heigh ho, the holly!” is found in Shakespeare’s play As You Like It. Both carols “Deck the Halls with Boughs of Holly’’ and “The Holly and the Ivy” praise the holly.

For those born between December 22 and January 19, the Native American totem animal is a goose. Geese have been significant figures in religion since Ancient Egypt. Geb (The Great Cackler) was a part of the Egyptian creation myth; he cackled so hard, he laid an egg that was the sun, the supreme deity RA. Fowl were a major food source in the ancient world. Egyptians domesticated ducks and chickens and kept them with geese, because one characteristic of geese was their awareness of danger. They signaled with their cackling any danger to the flock.

The goose was associated with the Roman goddess Juno, wife of Jupiter and mother of Mars and Vulcan. She was the goddess of fertility, marriage, and childbirth, all qualities of geese. Geese take only one partner for life, are extremely protective of their families, and warn with their cackling when they sense danger. In one instance geese saved Rome from the advance of the Gauls.

China, Korea, and Japan also honored geese in writing and art. “Wild Geese at Haneda” (1837-38) (14.5”x10”) is a Ukiyo-e woodcut by Hiroshige. It depicts a vast marsh of reeds, distant houses and the gate to the Benzaitin Shrine and trees behind it. At the left foreground are two houses, a small stand of trees, and fish nets hung to dry. White sails and the dark silhouettes of boats can be seen in the distance. The familiar wedge shape of a flock of flying geese can be seen at the top of the print. For security, geese flock together and take turns leading the migration. They know where they are going. If one of the flock falters, another goose stays behind until the other is well or dies. Geese are considered reliable, faithful, compassionate, and good at teamwork. Beyond their warning cackles, the goose quills are among the best for pens, possessing the magic to inspire.

Note: The setting of “Wild Geese at Haneda” iis the present-day site of the Haneda Airport in Tokyo.

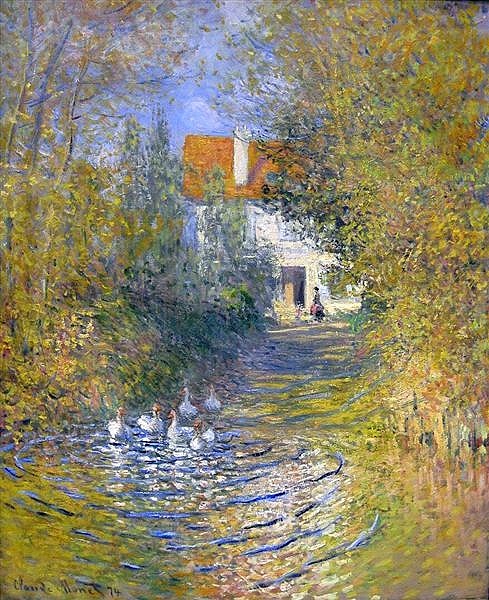

Monet’s “Geese in the Creek” (1874) (29”x24”) is an early example of Impressionist painting. Six white geese swim peacefully on a flowing stream surrounded by tree. Using bold dashes of all the complementary colors– oranges playing off against blues, yellows against purples, and reds against greens–Monet has created a lively forest. The white geese and white house with the orange roof give structure to this energetic painting.

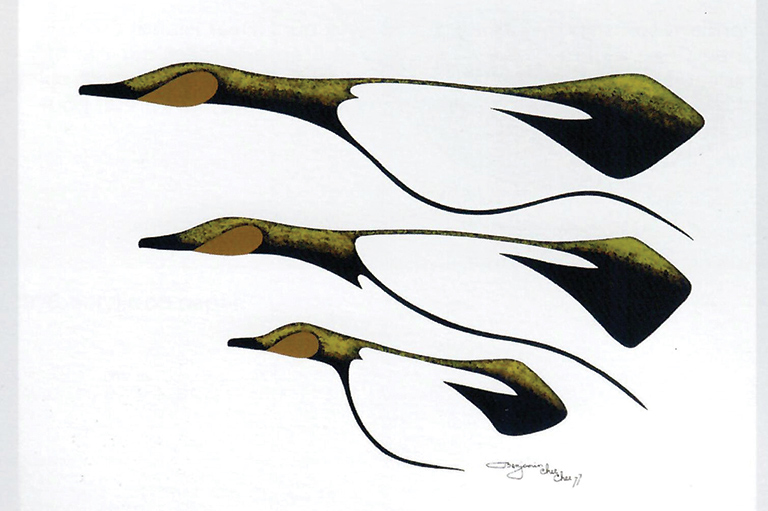

“Goose Family” (1975) was painted by Ojibwa Canadian artist Benjamin Chee Chee (1944-1977) and is an excellent example of Chee Chee’s art. Images of animals, particularly swallows and geese, were his trademark. His style was modern, and he refined his images into a few simple, graceful, and expressive lines. His friend Ernie Bies described watching Chee Chee work: “It was fascinating to watch him at work. Although his hands had a slight tremor, when he picked up his paintbrush they became rock-steady. Focusing on a blank sheet of paper, he would create the wing of a bird in one continuous fluid motion. Without measuring or sketching in advance, he instinctively knew where to begin and to end the brush stroke, how much paint he needed, and when to turn the brush.”

Chee Chee’s art can be linked to the Native American Goose totem. “Goose Family” was painted in 1975. Like the goose, Chee Chee was family oriented, but he spent most of his life without his family. His desire for a mother is clearly depicted as the mother goose’s wing lovingly encircles the young goose. After a twelve-year search, he found his mother in 1976. His father died when he was an infant, and he was separated from his mother for long periods of time in foster homes and for four years at the notorious St. Josephs Training School for Boys, a Roman Catholic reform school. There he and hundreds of young men were physically abused. He struggled with alcohol abuse for the rest of his life, but he managed to become what he wanted to be: an artist whose work was instantly recognizable.

Chee Chee’s first solo exhibition was in 1973 at the Nicholas Art Gallery in Ottawa, and he became successful and sought after. His acrylic paintings were so popular that he was requested to make limited edition prints of the originals.

“Family in Flight” (1977) is one of Chee Chee’s last paintings. He and his family are together. He planned a series about finding his mother. He referred to the animals in his paintings as “creatures of the present.” He rejected the category of Indian artist, saying “I think of myself as an Ojibway artist—a member of the Ojibway nation. I like to express my own feelings, not my Indian-ness. I express myself, the way I feel.”

Unfortunately, his mother and close friends, who had become his family, could not prevent this talented and loved artist from committing suicide on March 14,1977. He often told his friends that when he died he wanted to come back as a bird so he could “soar through the heavens forever.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.