Hung Liu was born in Changchun, China, in 1948. Her father was an officer in the army of Chiang K’ai-Shek. When Mao Zedong and the communist party took over on October 1, 1949, Hung Liu’s father was sent to prison, and her mother was forced to divorce him to save her new born daughter. Hung Liu went to live with her grandfather. She began drawing by age five: “One beautiful day in the late spring of 1954, I went outside with my grandpa, who was a middle school biology teacher. We both loved the outdoors–the wild flowers, the bugs, the birds, and everything we could see in nature. I brought my sketchbook with me as always. I was six years old, and that was the first time I tried to draw trees–there were a lot of them. I had a hard time doing it. Finally, I showed my finished drawing to grandpa–I was quite frustrated with the representation of the trees. Grandpa was like one of my teachers at school–he looked at my drawing, took a moment to meditate, then wrote down my grade–95. I guess he didn’t like the way I drew the trees. As I was just about to take my sketchbook and walk home, grandpa crossed out the 95 and put down 100! I was surprised and speechless.” (Hung Liu, 2010)

In 1968 Hung Liu was sent to Da Dulianghe re-education camp where she worked as a farmer for four years. She managed to make small drawings which she named “My Secret Freedom” (1968-1972). She also took photographs with a hidden camera of the peasants and gave them to them as gifts. Most families had destroyed their photographs to protect themselves.

After her release from the camp, Hung Liu attended the Beijing Teachers College as an art and education major. She received her BFA in 1975 and her MFA from the Central Academy of Fine Art in 1981. From 1981 until 1984 she taught at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing. Hung Liu was allowed to go to the United States to study art in 1984. She received an MFA (1986) in Visual Arts from the University of California, San Diego. She was taught only Russian realist art in her MFA program in China.

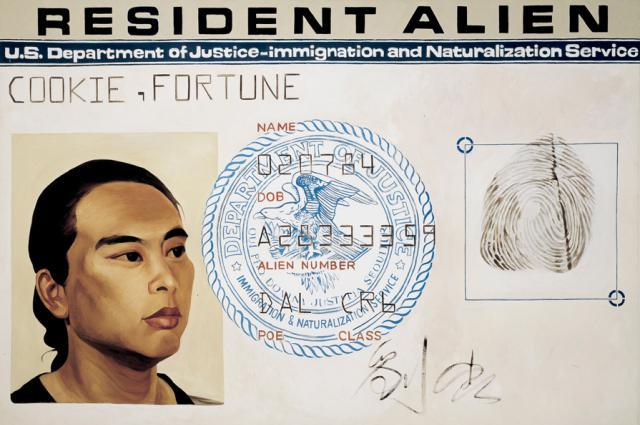

One of Hung Liu’s early works in America was “Resident Alien” (1988) (5’x7.5’), a large painting of her Green Card with her name as FORTUNE COOKIE, and the date of her birth1984, considering 1984 as the date of her rebirth. Hung Liu views fortune cookies as a symbol of her hybrid status: she was neither American nor Chinese, a multicultural condition. A rule-breaker, as she was in China, Liu made the words RESIDENT ALIEN large as a criticism of her status as an immigrant in the promised land.

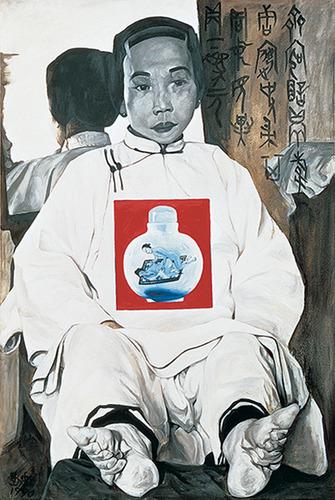

Hung Liu began to teach Chinese History in1987 at the University of Texas, continuing as Assistant Professor of Art from1988 until 1990. From 1990 until she retired in 2014, she was a professor of art at Mills College in Oakland, California. Among her first works in America were paintings that criticized conditions in China. “Virgin-Vessels” (1990) (72”x48”) depicts a young Chinese girl, with a perturbed look on her face, sitting in front of mirror. Her age and her white clothing reinforce the title of the work. Her feet, which project forward, are twisted and deformed. She is a victim of Chinese foot-binding, where the toes and arch are broken and bound to the sole of the foot. Women are then unable to walk. Girls were told that it made them more marriageable, as men liked small feet. However, most of the girls were forced to sit still, and were put to work making yarn, cloth, mats, shoes, and fish nets. The practice was more an economic necessity than a way to a better marriage.

Hung Liu has placed a red square on the white costume of the girl. The color of red has been for centuries a symbol in China of the sun, fire, and the heart. It represents power, celebration, prosperity, and it is said to repel evil. It also represents fertility. Quotations from Chairman Mao is alternatively titled the Little Red Book. In the center of the red square, Hung Liu has painted a white Chinese vase/vessel. On it she has painted in the traditional Chinese style a couple on a rug having sex.

“Jiu Jin Shan” (1994) is an installation commissioned by the De Young Museum in San Francisco. It was part of a larger exhibition titled The Other Side: Chinese and Mexican Immigration to America. Jiu Jin Shan is what the Chinese call San Francisco; the English translation is Old Gold Mountain. The mountain and the roadbed are formed from 200,000 fortune cookies; the railroad tracks crisscrossing the floor are taken from the Sierra Nevada section of the transcontinental railroad. Liu painted several Chinese sampans, sailing ships, on blue walls of the gallery. The ships around the room are smaller, as if they are coming from far away. When Europeans first saw Chinese ships, they called then junks.

“Three Fujins” (1995) (96”x126”x12’’) was influenced by a photograph taken in the 1880’s during the Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty in China. The Fujins were concubines of the royal court. In full make-up, they are dressed in court finery with flowered headdresses. They sit rigidly, with little expression, as they pose for the camera. Hung Liu’s use of oil paint thinned with linseed oil is allowed to run in long drips of color over the painted surface. The painting is an early example of this technique, which became her signature style.

The three black wire bird cages are real, not painted. They hang from the front of the canvas and represent the caged life of the fujins who would remain trapped like birds for their entire lives.

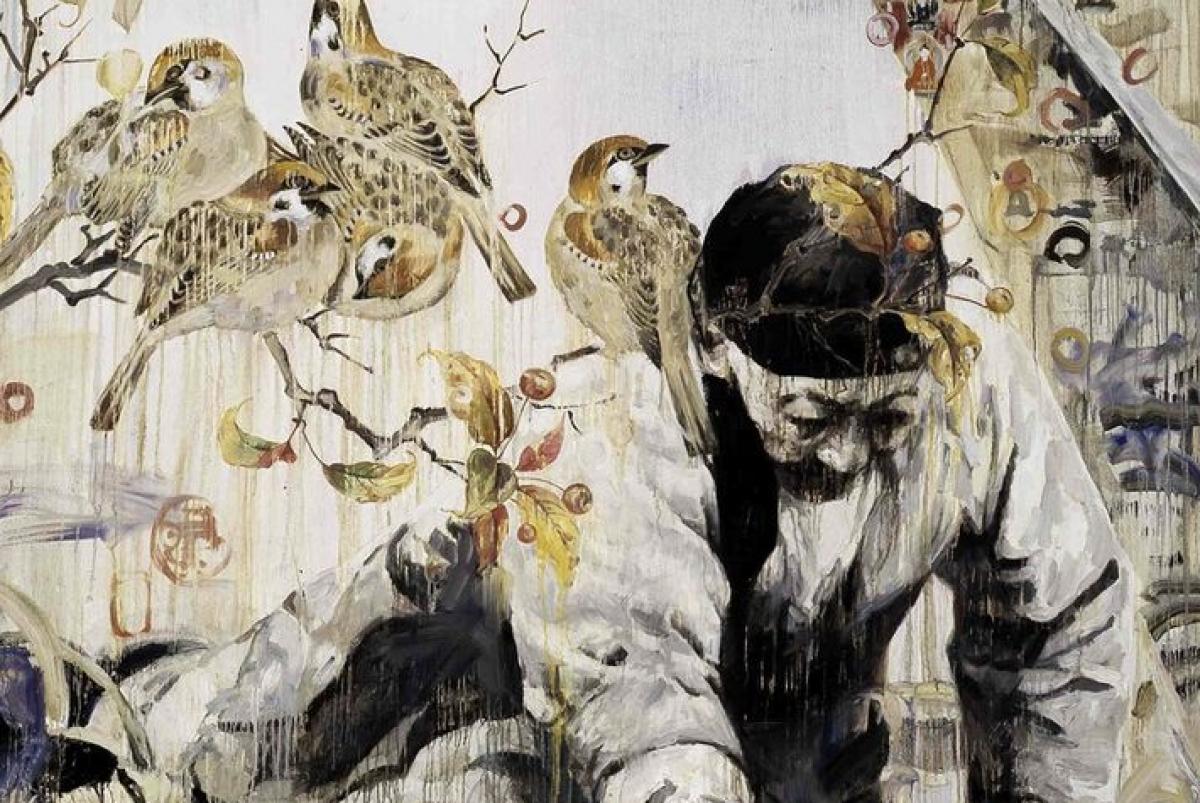

“Rice Sweeper” (2000) (80’’x80’’) represents Hung Liu’s fully developed style. The subject is an elderly Chinese person who uses a bundle of straw to sweep up the grains of rice that have fallen by the wayside. It speaks of the hardships experienced by the common people in China during the wars and revolutions. Other Hung Liu’s paintings have a similar theme, depicting hungry children eating the small amount of rice to be had, a woman working a hand loom, and women pushing the wheel of a millstone. Hung Liu uses linseed oil to thin the paint so that it runs down the canvas, which creates a unique atmosphere.

Hung Liu places a mother hen and her two chicks at the lower left corner of “Rice Sweeper.” Chickens were domesticated in China by 6000 BCE. They are considered benevolent and faithful. Roosters represent the Sun as they crow every morning at sunrise. Balancing the composition, six small images of the Buddha are placed at the top right corner. They are seated cross-legged in the lotus position for meditation.

Four sparrows sit on the branch of a fruit tree above the rice sweeper’s head. A fifth sparrow sits on the old man’s shoulder. In China, the sparrow is an auspicious sign of happiness and the coming of spring. Hung Liu includes these symbolic references to abundance and happiness as a sign of hope in the struggle of the common people to survive.

The Chinese communist government pursued the “Four Pest” campaign from1958 until1962 to eliminate rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. Sparrows ate grain, seeds, and fruit, and the campaign was intended to increase crop yield. When it became obvious the rice crops were diminishing because the sparrows were not there to eat the huge number of insects, including locusts that attacked the rice, Mao Zedong ordered an end to the sparrow killing. He redirected efforts to the elimination of bedbugs.

Hung Liu explores many themes in her art, bringing her work world-wide attention. Part II on Hung Liu will touch another of her themes.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Marian says

Incredible work, it doesn’t get better than this and thanks for introducing us to her. I’ll be in SF next month and hope her installation will still be at the De Young Museum.