St Patrick (c. 385-461 CE) is best known as the Patron Saint of Ireland. He was from a Romano-British town and went to Ireland as a missionary. He became the Bishop of Armagh in 432. Although never canonized, he is considered a saint by Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran churches. Unfortunately, there are no images of him during his lifetime.

That is not to say the early Irish church had no art. Ireland was not invaded by the Vikings or others from 400 until 750 CE, because the island was so far to the west and the sea and coast surrounding it were extremely dangerous. More Catholic missionaries, particularly St Colomba (521-597 CE), who came to Ireland in the 6th century. He was very active, and by age 25 he founded 26 monasteries, among them Durrow (553/556) and Kells (554). Ireland was a collection of independent kingdoms, each headed by a warrior and each with an abbey and monastery. Since there were no books/Bibles as we know them, the monks made it a mission to copy, decorate, and teach from early Christian texts. Using designs from their traditional craft of metal work on swords, they created magnificent illuminated manuscripts. These manuscripts are treasures of Irish art.

An elaborate cross page (also called carpet page) began each chapter of the gospel books. The “Carpet Page” (c. 680) (192v) (chapter of John, Book of Durrow) depicts a small gold cross within a white circle that is buried in the center of the page. The cross is surrounded by red, green, and yellow Celtic knots. The design, taken from knot patterns that existed as far back as the Roman Empire, is called an interlace or a plait. The knots, formed from intricately woven strands of color, have no beginning and no end, symbolic of the Christian belief of heaven as eternal life.

The interlace was commonly used in Celtic art from c.600 through 900, and it was symbolic of “horror vacuii,” the fear of empty spaces or fear of the unknown. The dark forests, long cold winters, and raging storms gave rise to these fears and were reasons to protect people and their possessions by filling every empty space with protective walls and fences. On this page, the cross is first protected by the interlace and then by a yellow circle representing the light of heaven and the sun.

Beyond the square yellow wall protecting the cross are six other walls. Four border walls are placed across the page and one along each side. Trapped within these walls are evil, frightening forces. The top and bottom walls contain red and yellow interlaced creatures resembling snakes. Perhaps this is a source of the legend that St Patrick drove the snakes from Ireland. Each creature’s mouth is securely clamped onto the tail of the one ahead of it. No one can escape or break this chain. Bound in the two side walls, six green and yellow animals are more clearly defined. Their long mouths clasp the hind legs of the ones ahead of them. The figures appear to have four legs, making them more closely resemble wolves and other four-legged beasts.

Each of the four gospels begins with a cross page in the manuscript. In addition, the first letter of the first paragraph of each book is given a full page and is heavily decorated. The Latin text was diligently copied and decorated with additional images called drolleries, small decorated images in the margins and between paragraphs. The drolleries could include the interlace but were also grotesque and fantastic figures made by combining different animals and humans. These filled the spaces around the text to provide a safety net around the written word.

The books were written and illustrated with quill pens made from goose feathers, on vellum, a finer quality of parchment, made from the soaked, stretched, and finely scraped skin of young calves or lambs. Both sides of each piece of vellum were used, and each book required about 120 skins.

The monks created these intricate patterns from their imaginations. The “Carpet Page” (c. 710-720) (13.5’’ x 9.75’’) (259 pages) from Luke’s gospel in the Book of Lindisfarne is regarded as one of the most spectacular. Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne (698-721), is generally accepted as the artist. Luke’s cross extends the width and height of the entire page, with five small crosses placed within white circles. The center white circle contains an eight-petaled flower consisting of four verdigris and four red petals. Verdigris was created by suspending copper over vinegar, and red was produced from toasting lead. Each monk made his own inks and some, like Eadfrith, were very successful in producing color that remains vibrant even until today.

Eadfrith’s interlaces give the impression of layers. The green and red interlaces are prominent, but they are interwoven with a smaller and more intricately detailed interlace in sandy gold. In other areas sandy gold snakes are interlaced with vibrant blues and small checkerboard designs. The intimacy and repetitiveness of the designs generate a mesmerizing and meditative response by the creators of the manuscripts and by viewers alike. The entire process of making the vellum and ink and copying and decorating the manuscripts was intensely spiritual and required several years for completion.

The Book of Durrow and the Book of Lindisfarne pre-date the Book of Kells (c. 800). Although the cross pages and initial pages are found in all the books, the monks also attempted to depict the four gospels with the symbols for each: Matthew the angel, Mark the ox, Luke the lion, and John the eagle. The metal work that influenced the decorations had no human or animal references for the monks. However, with the passage of time, the monks attempted to depict the gospelers as people.

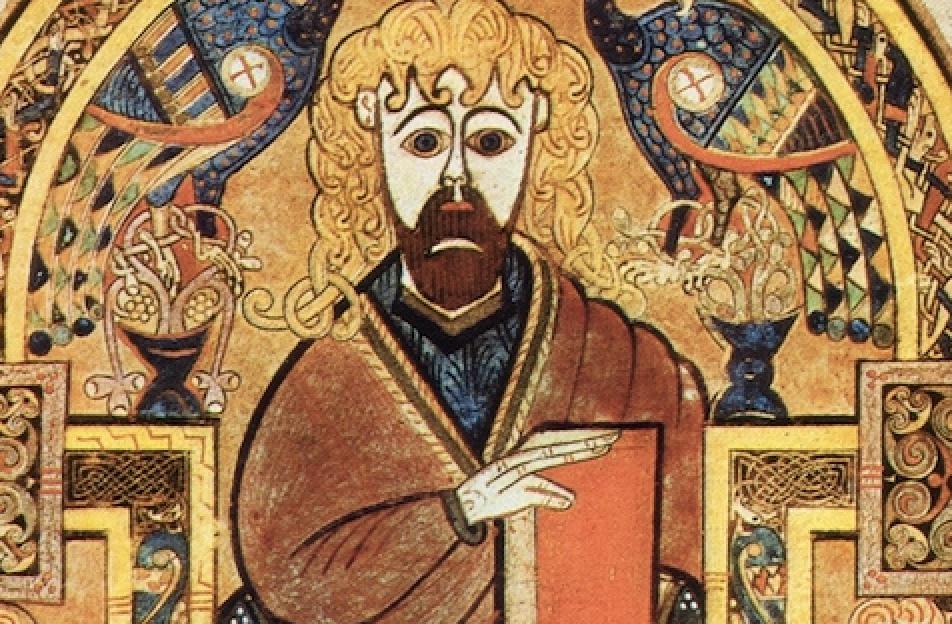

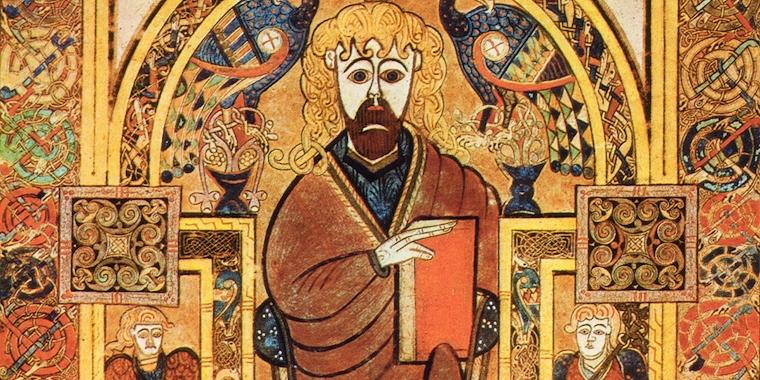

Apart from the theme of Irish crosses for this St Patrick’s day article, the depiction of “Christ Enthroned” and “Madonna and Child” provide another interesting look at the work of the Irish monks.

Still using the interlace and enclosing the figure with walls and borders, the Illuminator of “Christ Enthroned” in the Book of Durrow depicts Christ presenting a Bible to the viewer. His left hand, hidden by the cloth of his robe holds the book, while his right hand is in the position of a blessing. The four visible fingers are divided two by two. Wrapped and in an orange-red cloth, Christ is seated on a throne with two blue cushions that project from either side of his upper torse. His blue tunic can be seen at his neck and over his knees. His sandalled feet project to either side. Without knowledge of proportion or anatomy, the monk produced an imposing figure.

The four figures placed beside Christ may represent the four gospels or may be four protective angels. Christ is depicted as a blond, with the curls of his hair resembling a loose interlace. His large eyes stare intently at the viewer. His dark red beard is very Irish. On either side of him are vases of plants. On his right, a dish of grapes suggests the wine of the Eucharist. Not as clear, the plant on the left might represent wheat for the bread of the Eucharist, or alternatively the Tree of Life. In the arch above Christ’s head are two peacocks, symbols of eternal life. From ancient times, it was believed that when the peacock died its body did not decay, but remained as it appeared in life.

The image of “Madonna and Child” in the Book of Kells includes the borders and interlaces and guardian angels. It also contains the first known depiction of a woman in Irish manuscripts. Mary’s upper body is depicted frontally with the Christ Child on her lap. The artist changed position with her lower body, her knees and feet turned to the side. She holds Christ around the waist. He reaches up to touch Mary with His left hand, while His right hand is placed upon her right hand. The monk has attempted a complicated pose. Depicting a baby was not successfully accomplished until the Renaissance. The monk has given Christ Irish red hair.

May the roof above us never fall in.

And may the friends gathered below it never fall out. (Irish Blessing)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.