Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, (b.1940, St. Ignatius Flathead Reservation, Montana) is an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and also is of French-Cree, Metis, and Shoshone descent. She was named Jaune, the French word for yellow, in recognition of her French Cree ancestry. Her grandmother gave her the name Quick-to-See because of her ability to understand things quickly. Smith received a BA in Art Education (1976) from Framingham State College in Massachusetts. She was told that she was more skilled than the men in her class but could not expect a career as an artist. Undaunted, she began earning a living as an artist in the 1970’s. In1980, she received an MFA from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

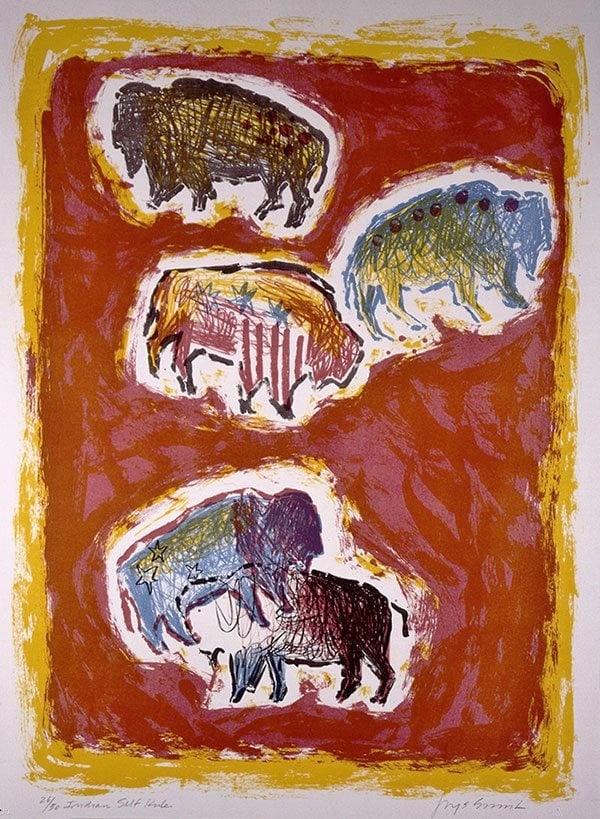

Untitled (From Portfolio of Indian Self Rule) (1983) (24” x10’’) (color lithograph) (Smithsonian American Art Museum) depicts five buffalo, for Smith a symbol for Native Americans. The print features a yellow frame around a field of red ochre, Indian red. The buffalo at the top is brown and black, but the inclusion of yellow indicates a tanned hide. The red circles on its back may represent wounds. Smith’s use of black represents smoke or charcoal. The second buffalo is yellow and blue with seven black wounds. Smith uses blue to represent America. The third buffalo hide has blue stars and red bars of the American flag. The two lower buffalo are blue, yellow, red, and black. The herds of living brown buffalo have disappeared. This print was included in the book Indian Self Rule: First-Hand Accounts of Indian-White Relations from Roosevelt to Reagan (1983).

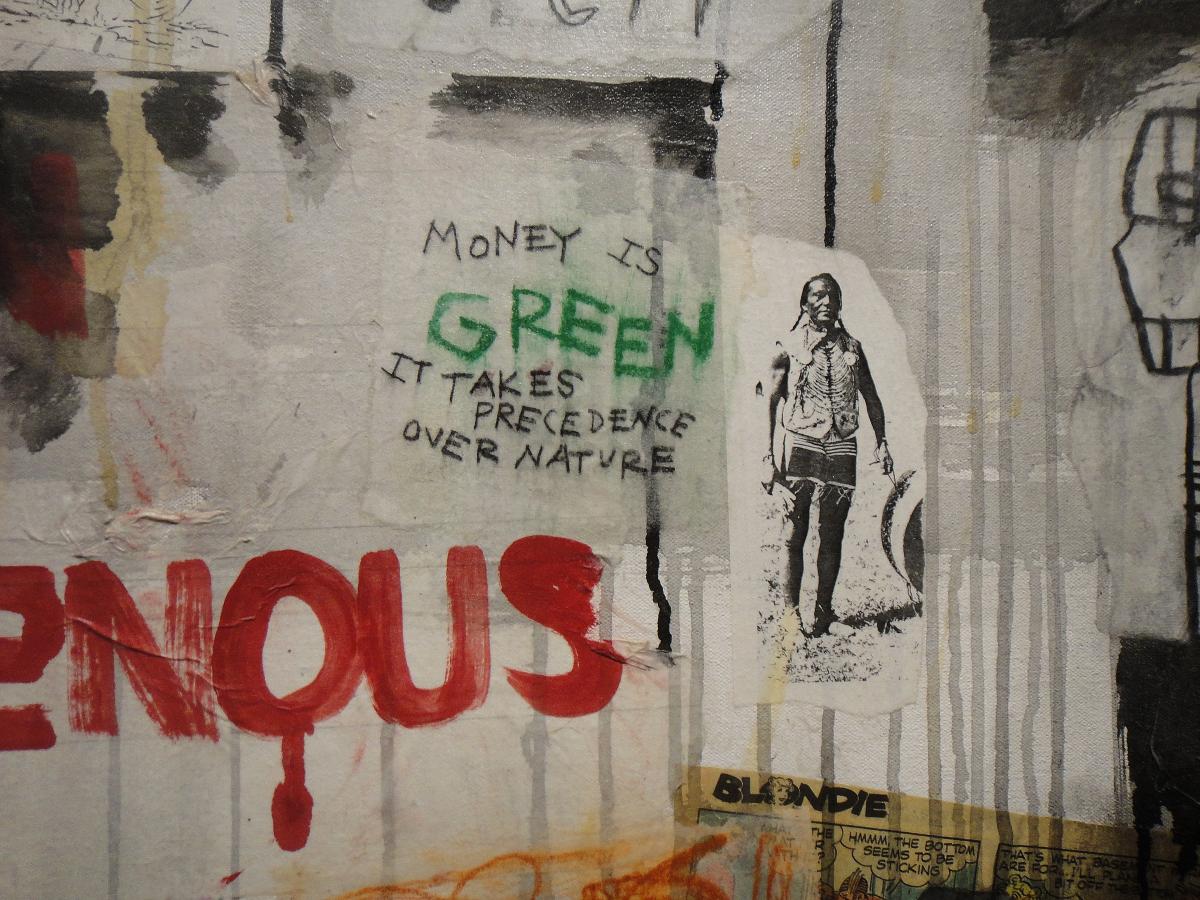

Smith’s paintings developed to include drawing and collage. Collaged items incorporated were taken from mass media, advertisements, maps, cartoons, scientific articles, newspapers, photographs, and other materials that seemed appropriate for her subject. Her time in graduate school had introduced her to Abstract Expressionist artists including Pollock, Still, and Rothko, thus her use of patches of color and drips of paint. Smith researches her subjects until she fully forms her intention for the work.

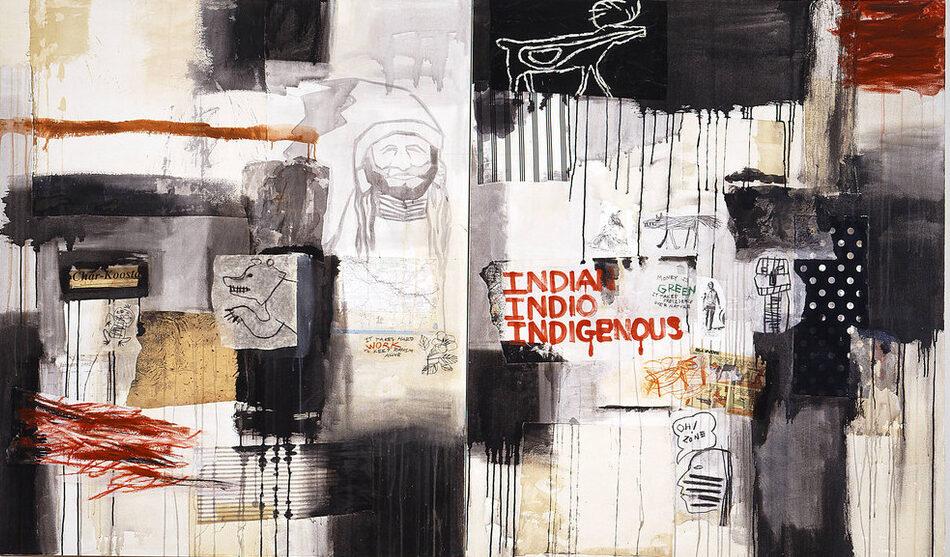

“Indian, Indio, Indigenous (1992) (60’’x 100’’) (National Museum of Women in the Arts) is part of Smith’s series The Quincentenary Non-Celebration, created in 1992. It was a response to the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in America. Spain and Italy held celebrations for Columbus in 1992, and the United States Mint struck a Columbus Quincentenary one-dollar coin. However, Indigenous People’s Day honoring Native Americans was a popular American response.

Smith collaged the masthead of her tribal newspaper Char-Koosta, and next to it collaged a drawing of a bear. She placed in the center a gray wash drawing of an Indian. The title of the painting is written boldly in red capital letters. Smith includes a smaller drawing of an Indian warrior’s head with the words OH! ZONE in a cartoon bubble. A reindeer petroglyph is placed at the top of the work.

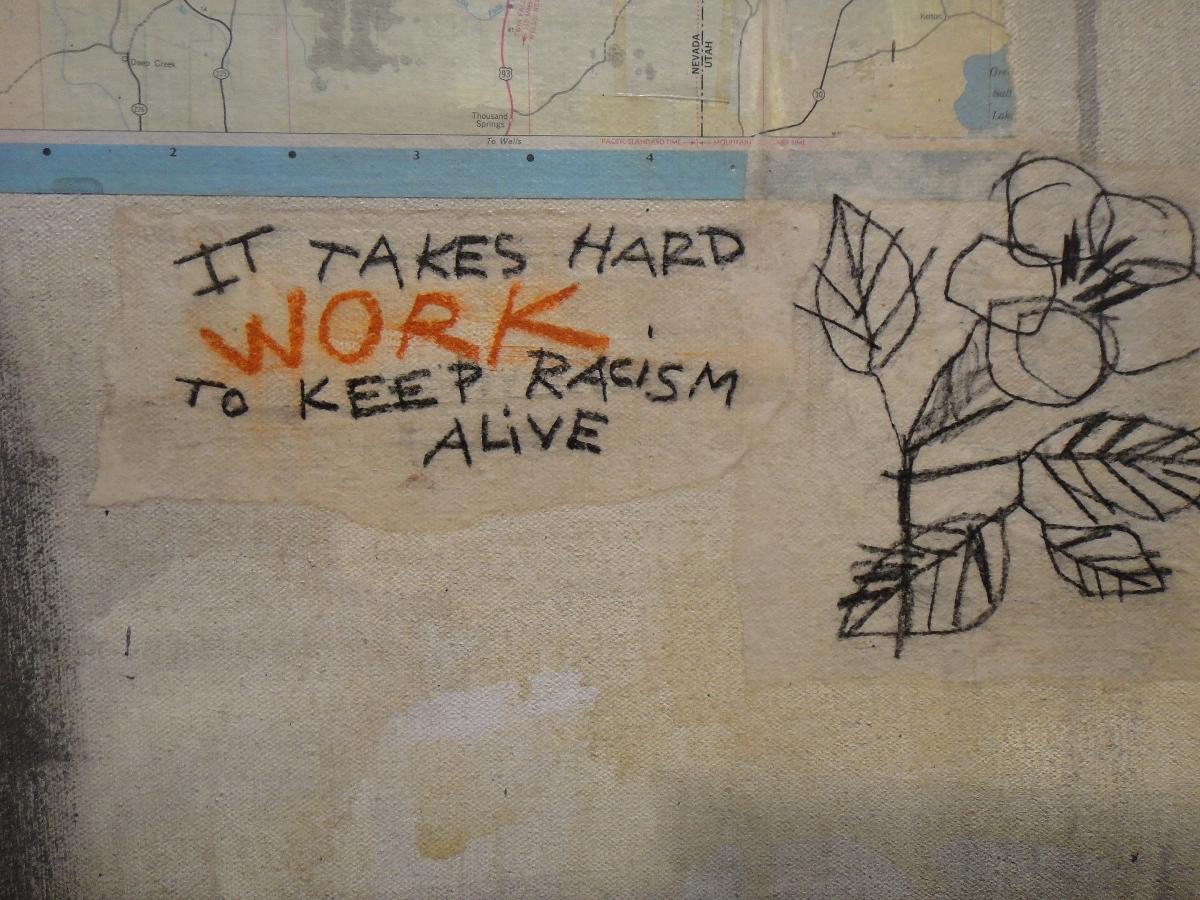

Beneath the drawing of the Indian is a flower with leaves drawn in black and the words IT TAKES HARD WORK TO KEEP RACISM ALIVE.

Farther right are the words MONEY IS GREEN/ IT TAKES PRECEDENCE OVER NATURE and a black and white photo print of an Indian. Below the Indian, Smith has collaged part of a BLONDIE comic strip.

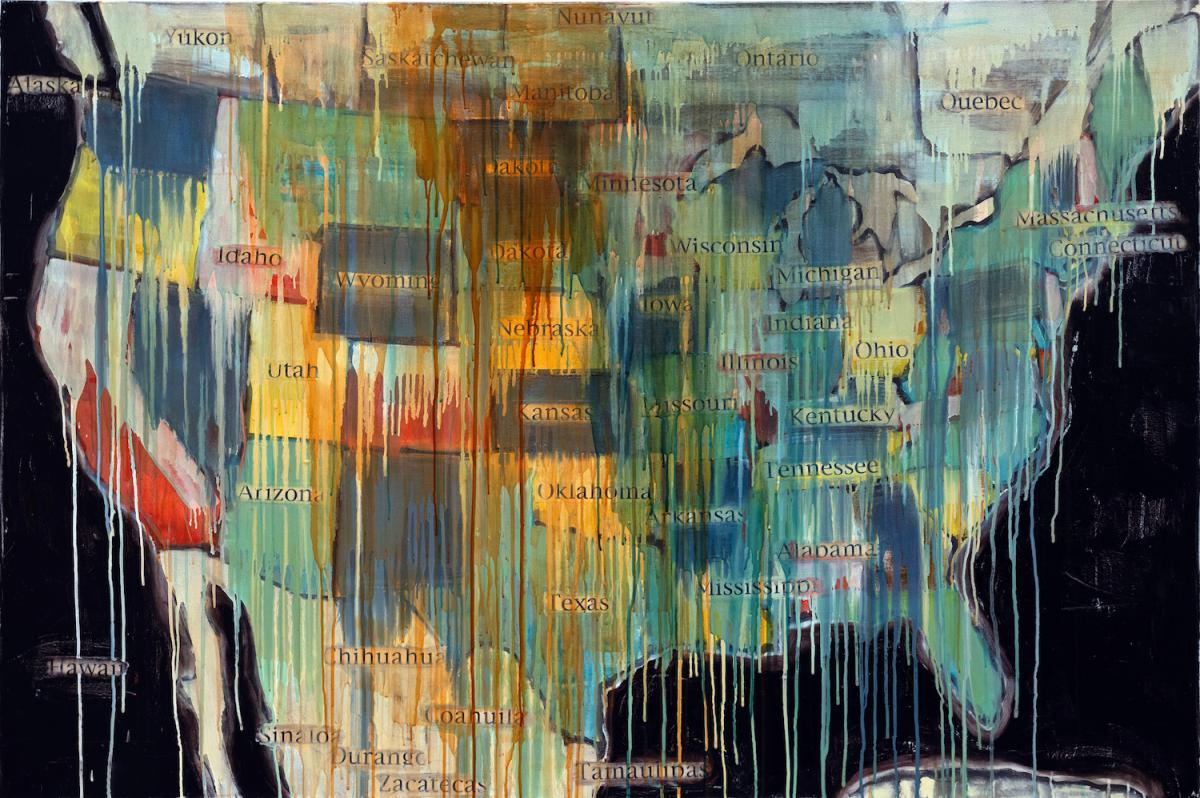

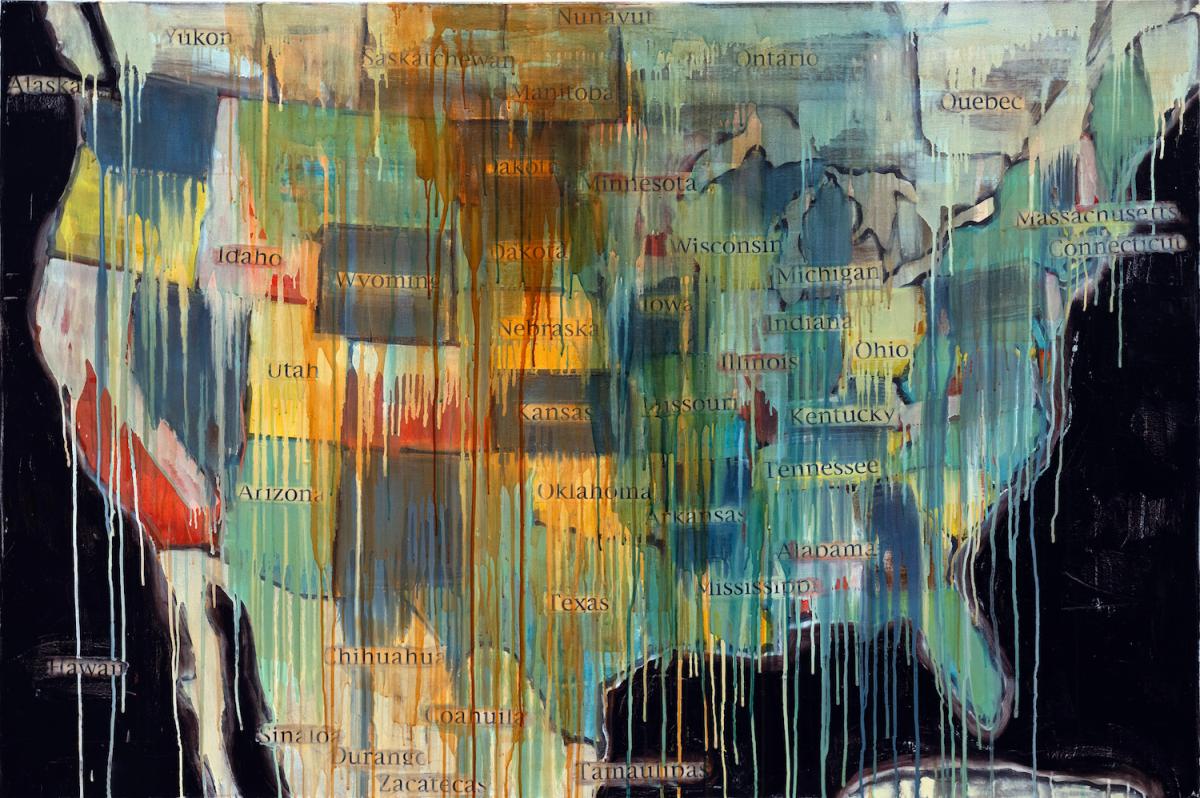

Smith began painting a series of American maps in 1992, and she continues to add pieces. In 2000 she painted the map “Browning of America.” The 2001 “Tribal Map” includes the names of Native American tribes. “State Names” (2000) (48”x72’’) (SAAM) includes the names of 27 states that have Indian names. Among the state names included are Connecticut (from the Algonquin language meaning long tidal river), Idaho (from the Apache language), Michigan (meaning large lake), Mississippi (from the Choctaw language meaning great water, or father of waters), and Oklahoma (also from the Choctaw language meaning red people).

Discussing the maps in 2004, Smith stated, “We are the original owners of this country. Our land was stolen from us by the Euro-American invaders…. I can’t say strongly enough that my maps are about stolen lands, our very heritage, our cultures, our worldview, our being. Every map is a political map and tells a story — that we are alive everywhere across this nation. …”

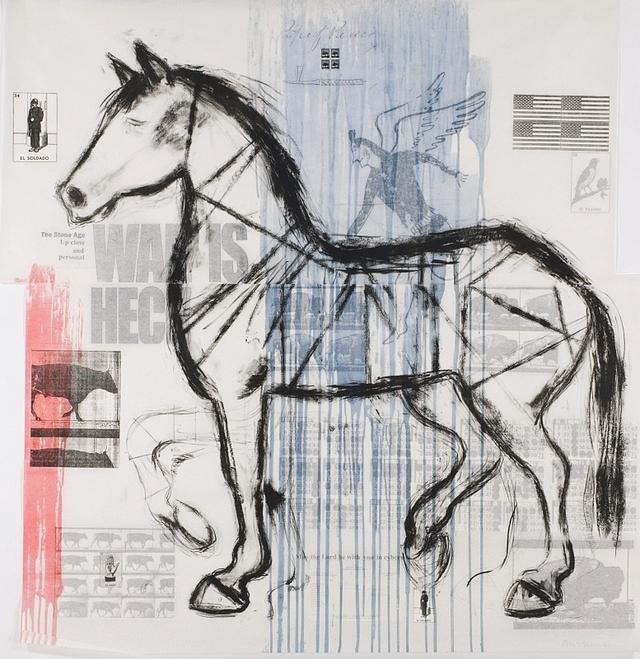

Smith’s work consistently responds to world events. “War is Heck” (2002) (lithograph) (59”x 57”) (Whitney Museum, New York) includes Native American images as a protest to war. She frequently uses the image of a horse as a stand-in for herself. The horse does not run, but it prances proudly in the center of the composition.

The center of the composition is light blue and includes the image of an Indian with wings riding the horse. In this work blue was not intended to represent America, but peace. Faintly written at the top are the words peace pipe. Below are four small buffalo and a peace pipe. A double image of the American flag, with a bird perched on a tree branch is next to the peace pipe.

The small light red area at the left speaks of blood and war, and a black bull running forward may indicate a rush to war. Below, rows of smaller bulls are stopped with an upraised hand. A small image labeled IL SOLDADO (soldier) appears at the top left. Numbers of buffalo walk behind the major images.

Smith’s comments regarding this print are timeless: “Are we so inured to war that we accept it as the way to solve problems between countries? Americans have come to believe that we can single out some international bad guys and with high tech equipment ‘take them out,’ neatly, cleanly solving problems for the whole planet…. People are herded from their homelands and treated like sub-humans by corporate governments who value oil over humanity.”

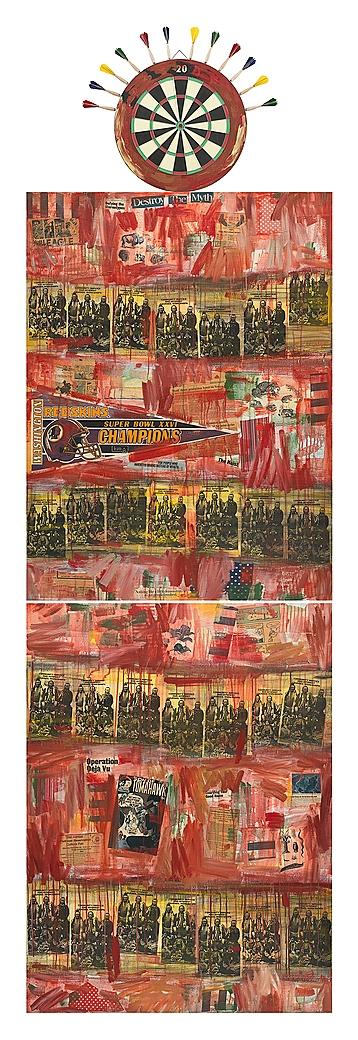

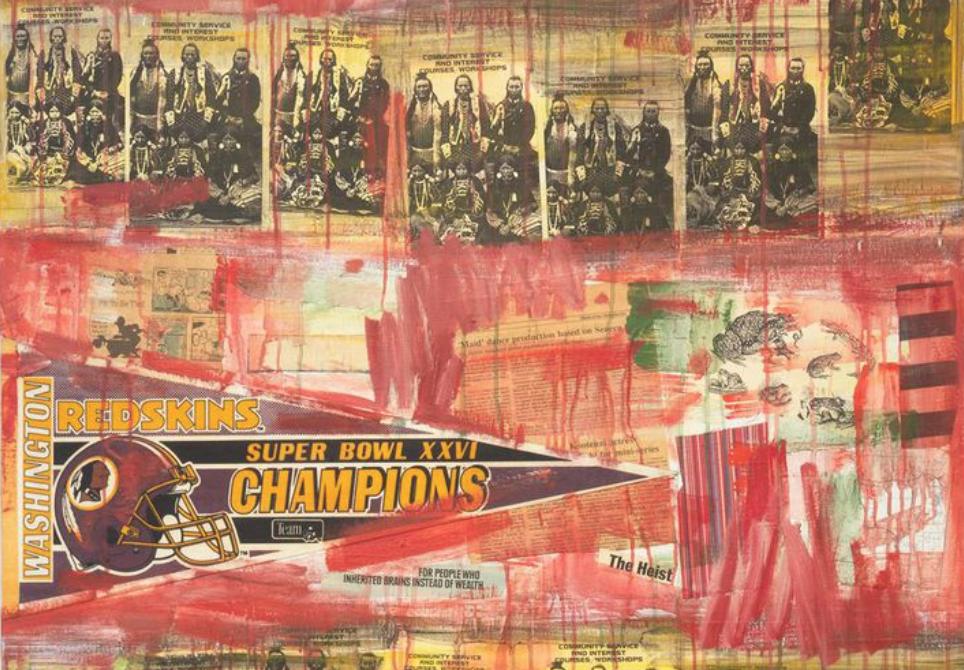

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, purchased “I See Red” (1992) (11’x 42’’) in 2020. It was the first work by a Native American artist purchased by the Gallery. Above the painting is a dart board with the darts arranged in a semi-circle around the target to resemble feathers in an Indian headpiece. The eleven-foot painting is complex and is divided into ten layers alternating painted red sections with a repeated patterns of Indian photographs taken from the Flathead reservation newspaper Char-Koosta News. The text COMMUNITY SERVICES, FIND INTERESTS, COURSES WORKSHOPS appears at the top of each photograph. Under the target are the words Destroy the Myth, which Smith has stated mean, “The myth is that Native warriors were at war all the time like the Europeans. Only we didn’t have horses or steel swords or guns.”

Very clearly in the second red section is a Redskins Super Bowl XXVI Champions pennant, and an image of the team’s helmet. The Redskins’ victory was over the Buffalo Bills on January 26, 1992. Smith includes her usual images of buffalo as an additional comment. Beneath the pennant are the words FOR PEOPLE WHO INHERITED BRAINS INSTEAD OF WEALTH. Smith states, “I reference Indians being the Target of the corporate world of mascots and consumer goods.”

The misuse of Indian names was a long-standing issue for Native Americans. It was not until 2021, when the National Gallery purchased this painting, that the Redskins organization agreed to change the Team name.

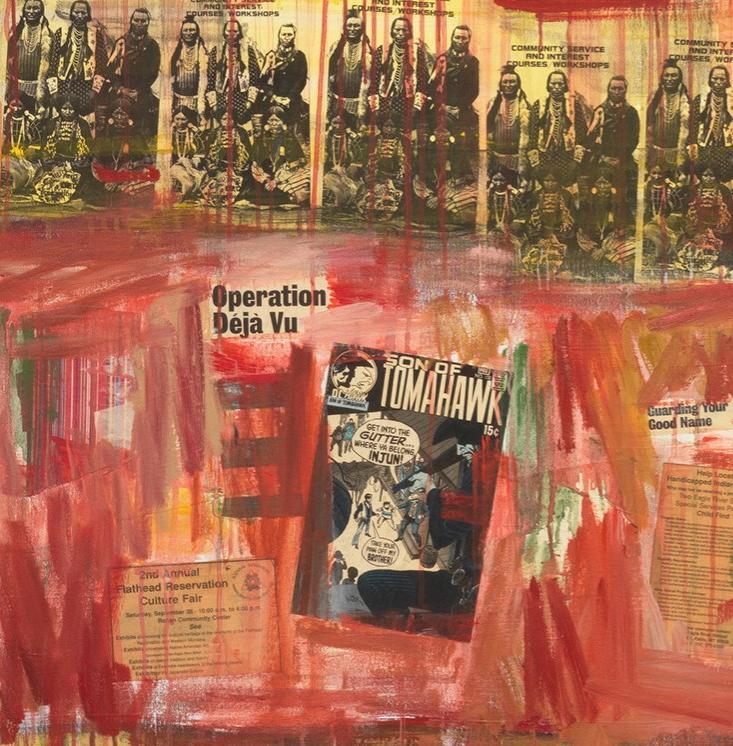

The fourth red section begins with the words Operation Déjà Vu and the cover of Son of Tomahawk, one of a DC comic series published from the 1950’s through the 1970’s. In one text bubble GET INTO THE GUTTER…WHERE YOU BELONG INJUN!” gets a response in another text bubble, TAKE YOUR HANDS OFF MY BROTHER. At the right side of the painting are the words Guarding Your Good Name. At the lower left side of the painting is an announcement of the 2nd Annual Flathead Reservation Culture Fair. Smith’s use of color and text in her painting need little explanation. She stands strong for her people and the way they are perceived.

In 2022 Smith stated, “My painting is caught in a perfect storm: Black Lives Matter, the death of George Floyd, Covid-19, the presidential election, the Standing Rock Sioux temporarily winning a stay on the pipeline and add to that the supreme court saying the Creek Indians do exist and their treaty is valid.”

Smith refers to the purchase of “I See Red” as breaking the buckskin ceiling: “Those of us who went to college were overlooked or disqualified as not being authentic. So, our artwork was considered to be bastardized. Many of our museums are filled with antiquities, but no contemporary art made by living Indians.”

Smith’s contributions include more than her enormous production of paintings and prints. She has been the recipient of numerous awards and grants. She brought indigenous artists from all over to participate in organized symposiums and collectives, and she curated over 30 exhibitions of their work. She has had more than 125 solo exhibitions and participated in over 680 group shows. Her work is in numerous museums and she has lectured at 200 universities, museums, and conferences.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.