Jeffrey Gibson (b.1972, Colorado), a member of the Mississippi Choctaw and Cherokee Nations. As a child, Gibson lived in Germany, Korea, and the United Kingdom. He received a BFA in 1995 from the Art Institute of Chicago. His MFA in 1998 from the Royal College of Art in London was sponsored by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians: “My community has supported me…My chief felt that me going there, being a strong artist, made him stronger.”

Trained as an abstract painter, Gibson believed he needed to be truer to his experiences, in his words, “especially my experience of having grown up moving around, always being an insider, an outsider or a visitor or a tourist. Utopia was important for me to envision and relates to my being Native American and having grown up solely in a Western consumer culture. My desire…was a reaction to Native tribes being consistently described as part of a nostalgic and romantic vision of pre-colonized Indian life. [My] differences funnel through me, a queer Native male born toward the end of the 20th Century and entering the 21st Century. I consider this hybrid in the construction of my work and attempt to show that complexity.”

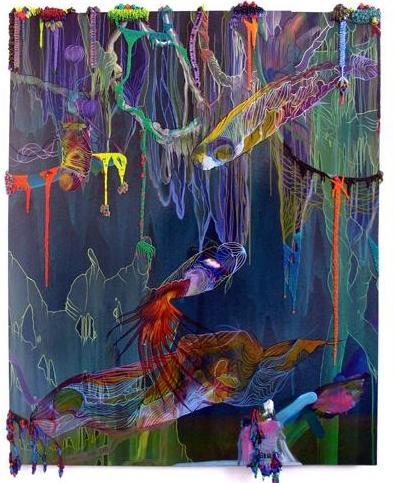

“Realm of Fin, Feet and Wing” (2005) (46”x57”) combines abstract and figurative elements that illustrate Gibson’s early style in a colorful and intriguing painting. Fish and wing images appear to swim through an imaginary world of water and sky, woven with strands of blue, green, and purple netting, touched with bold orange, bright pink, and yellow strands of color.

Gibson’s talent with bright color in abstract art has continued throughout his career. In 2016, he won the competition to design three stained glass windows for Houghton Chapel at Wellesley College. They are titled “To Become Day, Mean Solar Day, Evening Civile Twilight” (2016) (each 10.5’ x 3’). Never having worked in stained glass, he turned to Lyn Hovey, a well-known stained glass artist in Massachusetts. Gibson selected the colors for the window from over 300 colors. Gibson and Hovey directed the work at Hovey’s studio in Guatemala by four women weavers of Mayan ancestry. The windows contain over 5000 pieces of glass.

Circles radiate like suns, rays of light shine down, as the colors turn from sun rise, midday and return to evening. Although not specific, the color patterns reference Iroquois bead work from the 19th Century in Niagara Falls. Gibson remarked, “Both of my grandfathers were Southern Baptist ministers, and I know how important their churches were to them and the communities that they served. Here [at Wellesley], it’s just daunting how important faith is to people.”

During a period of depression, his counselor advised Gibson to try training on a punching bag. In 2014, he began making art with old punching bags. “Our Freedom Is Worth More Than Our Pain” (2017) (11.4’’x71’’x42’’) (repurposed punching bag) is one of more than 50 punching bags he has created. He uses glass beads, tin jingles, wool army blankets, and found objects to cover the punching bags with Native American beaded designs and powerful messages. Hanging off-balance from the arms of a scale, “Our Freedom Is Worth More Than Our Pain” speaks loudly of the long process of denying Native Americans their rights. As a gay man, Gibson also speaks to the uncertain status of the LGBTQ+ community.

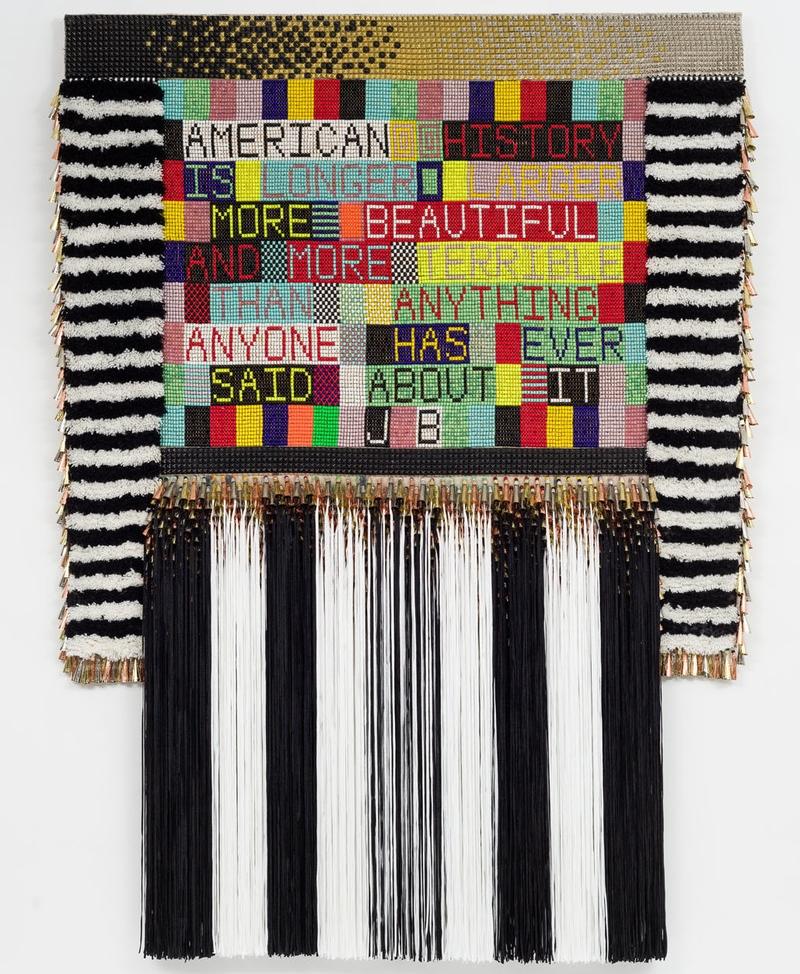

Gibson’s inspiration for “American History Is Longer, Larger, More Beautiful and More Terrible Than Anything Anyone Has Even Said About It, JB” (2015) (89”x66”x5”) is a quote from his hero, James Baldwin. As Gibson has said, he is inspired by his varied life experiences. Beyond the Native American influences of mythological figures, pow-wows, Iroquois beadwork, Kachinas, teepees and totem poles, his work also is inspired by Everlast punching bags, the punk and rave culture of London, dancing in night clubs, lyrics and titles of popular songs, and his favorite writers from Simone de Beauvoir to James Baldwin. Gibson’s art responds to and supports social and political concerns, environmental issues, and subjects of identity. His wall hangings include such titles as “Alive” (2016) (I am alive, you are alive, they are alive, we are living) and “Say My Name” (2018).

“Speak to Me in Your Way, So That I Can Hear You” (2015) (112” x53” x72”) (driftwood, glazed ceramics) reflects the Native American mythology of spirit walkers. The spirit walker goes into a trance, seeking guidance in the spirit world in order to gain knowledge to help solve a current problem. The spirit walker then returns and passes on this knowledge. Gibson frequently makes his art from found objects such as the driftwood that supports the spirit walker. Gibson’s spirit walker wears a magnificent cloak, with the title of the piece displayed in beadwork on the back. The first two letters of the word speak appear surrounded by yellow beads. Taking on a new challenge, Gibson learned the art of hand-built ceramics to make the mysterious face.

“So, this series of dreams was very much about these kinds of ancestral female figures that would guide me through this landscape, and they would always tell me, I guess, pieces of advice was how I read them at the time. This one, ‘Speak to Me in Your Way So That I Can Hear You,’ I remember was one of these figures kind of telling me to be quiet because I kept trying to tell them what I needed…and they kept basically telling like ‘You’re not listening.’ “

“People Like Us” (2018) (5’) is one of a series of sculptures inspired by Hopi Kachinas. They are religious figures, not dolls, each depicting one of 400 mythical beings in Hopi religion and used in teaching Hopi girls about their religion. Authentic ones are made only by the Hopi. “People Like Us” was inspired by a silkscreen print of the same name by Sister Corita Kent (1918-1986), that Gibson owns. “People like us” has become an expression used when referring to anyone who is different. This red faced, one eyed, funky, fun figure is different, but at the same time likeable.

Gibson describes his Kachina figures: “I would say they’re probably more Chinese warriors and Afrofuturism more than anything, but they really are a mash-up of intertribal aesthetics.”

“No. 4” (2019) is a photograph of one of 50 dancers wearing Gibson’s costumes in a 2019 performance at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The dance performance was part of the ongoing “Identity Project” at the museum to “shine light on gaps in the museum’s early collection, acknowledging those persons that are missing,” according to project director Dorothy Moss. Each of the Native American dancers identifies as LGBTQ+. The costumes have different names: “They Fight for Clean Water;” “Powerful Because They Are Different;” “Their Votes Count;” “They Speak Their Language;” “They Identify As She,” and “Their Dark Skin Brings Light.”

“Because Once you Enter My House, It Becomes Our House” (2020-2022) (44’x44’x21’) is a plywood and steel construction covered with posters. The work was commissioned by the Cordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts. The commission was a result of discussions about racial violence, American values, and American monuments. The directors of the Cordova Sculpture Park decided to mount an exhibition of three newly commissioned monuments. Gibson’s was the first.

Gibson selected the title from a lyric in the song “Can you Feel It” by Mr. Fingers (Larry Heard). The architectural design is a ziggurat shape from a pre-Columbian temple structure found in ancient Mississippi at Cahokia. Gibson worked with other Indigenous artists to produce the piece. Taken as a whole, the surface posters recall OP art images as well as Native American designs. Each side contains a message for the viewer. On the west POWERFULL BECAUSE WE ARE DIFFERENT, the north THE FUTURE .IS PRESENT, the east RESPECT INDIGENOUS LAND (pictured), and the south IN NUMBERS TOO BIG TO IGNORE, that refers to murdered Indigenous women.

Gibson reflects on his work: “As far as the Native American content in the work or the references, what I’m making is not cultural practice, which is very different than a lot of Native American artists who feel that they’re really making things for their community, to represent. This work is very much a sculpture which is using these references, but hopefully making them in a way that they also relate to iconic sculptures of the 20th century and previous. I am trying to make the world that I envision.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.