Martin Johnson Heade (b.1819, Bucks County, PA) is a unique American landscape and flower painter. His family ran the Lumberville Store and Post Office. Heade’s first art teacher was Edward Hicks, a folk artist and Quaker minister. Heade traveled abroad in 1838 to study art and lived in Rome for two years. When he returned to Pennsylvania, he showed his portraits at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and at the New York Academy of Design in 1841. He began exhibiting regularly in 1848. An itinerant portrait painter, he traveled along the East coast. He began to do more landscapes starting in the1850s. Heade settled in New York City in 1859 and worked at the Tenth Street Studio, where many of the Hudson River artists worked. Heade painted seascapes, salt marshes, and small horizontal landscapes, concentrating on lighting effects and atmosphere. He became friends with Kensett, Bierstadt, Gifford, and Frederick Edwin Church, whose “Heart of the Andes” (1857) (66’’ x130’’) he saw at the Metropolitan Museum. Heade made his first trip to Brazil in 1863.

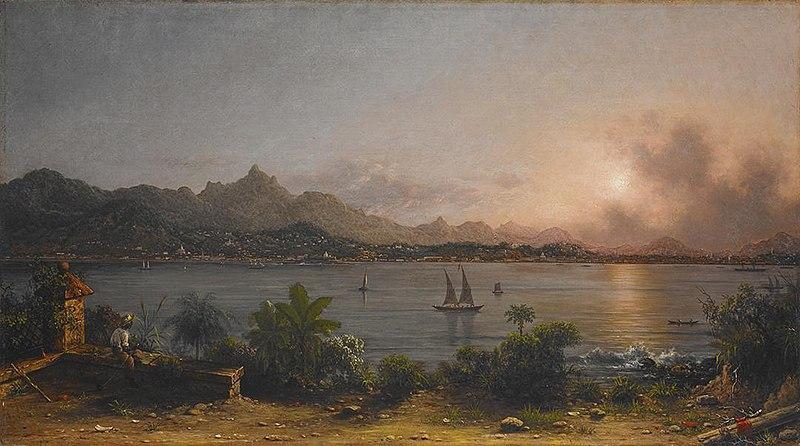

Church had visited Brazil two times and created large panoramic landscapes that excited New York art buyers. He advised Heade to do the same. Heade went with a different idea in mind. “The Harbor of Rio de Janeiro” (1864) (19.2’’ x 43.1’’), like all Heade’s paintings, was small and intimate. At sunset, the harbor stretches across the canvas with a few sailboats, a sandy shore with tropical plants in the foreground, and the City spread out below the magnificent mountains. It is quiet and peaceful. The Emperor of Brazil, Don Pedro II, liked Heade’s painting so much he made him a Knight in the Order of the Rose, an imperial order established in 1829.

Heade went to Brazil with the naturalist Reverend J. C. Fletcher who proposed to use Heade’s illustrations for his book Fletcher’s Study of South American Hummingbirds. Heade made 20 small paintings titled “The Gems of Brazil” for the book. More than 50 people bought subscriptions, but 200 were needed. The book was never published; however, Heade remained fascinated by orchids and hummingbirds, and he painted dozens of them, all different. “Cattleya Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds” (1871) (13.7’’ x 17.9’’) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) illustrates Heade’s attention to the smallest detail, his knowledge of his subject, and his remarkable ability to capture the atmosphere of the Brazilian jungle.

The Cattleya orchid, called the “Queen of Orchids,” was first discovered in Brazil in 1817, and it was named for English horticulturist and collector William Cattleya. Heade depicts a purple Cattleya orchid in all its splendor. It is one of the largest orchids and grows high in the jungle. Heade depicts the light green leaves necessary for the orchid to bloom. Dark green leaves do not support blooms. Victorian England loved orchids and attributed meanings to most flowers. Purple orchids were the symbol of dignity and authority. Giving a purple orchid to someone showed love and respect.

The hummingbird closest to the orchid is a ruby-throated hummingbird. The birds fly around their nest which is built on a slender branch, frequently in the fork. They build their small nests high above the ground where they are hard to see. The nests are often mistaken for a knot of wood. Hummingbirds have been popular over the ages and with many cultures. They represent good luck, joy, and love. Christians consider them messengers from God and a reminder to trust in Him.

A Boston Transcript article (August 1863) reported on Heade’s trip to Brazil: “It is his [Heade’s] intention in Brazil to depict the richest and most brilliant of the hummingbird family–about which he is so great an enthusiast–to prepare in London or Paris a large and elegant Album on these wonderful little creatures…He is only fulfilling a dream of his boyhood in doing so.” Brazil has 81 species of hummingbirds.

“Passion Flowers and Hummingbirds” (c.1870-83) (15.1’’ x21.58’’) (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) depicts black and white snow-capped hummingbirds. The iridescent green birds have white throats and bellies, separated by broad green collars, and white snow-caps. They are particularly attracted to passion flowers. Spanish Christian missionaries named the flowers “passion flowers” because they associated specific parts of the flower with the scourging, crowing with thorns, and crucifixion of Christ. The 10 red petals represented the 10 apostles, excluding Judas, and Peter who denied Christ three times. The corona rising from the center of the petals represents the crown of thorns. The styles coming from the center of the corona look like large-headed nails.

Heade supported Darwin’s theory of evolution explained in his book The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom (1876). Darwin specifically mentions that hummingbird beaks were adapted specifically to fertilize passion flowers. Heade was the first artist to paint several works paring the two.

Heade married Elisabeth Smith in 1883, and they settled in St. Augustine, Florida. From 1883 until his death, Heade painted over 150 works. “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica” (1887) is one of Heade’s largest paintings, measuring four feet by seven feet. It was commissioned by real estate developer Henry Morrison Flagler, also partner of John D. Rockefeller in the Standard Oil Company. Flagler wanted to make St. Augustine the “Newport of the South.” He commissioned Heade to make two paintings, “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica” (1887) and “The Great Florida Sunset” (1887), to hang in the upper rotunda of his Hotel Ponce de Leon. The hotel included seven artists’ studios, one of which Flagler gave to Heade.

In “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica” Heade returned to painting horizontal landscapes, having painted so many early in his career. The sun shines across the foreground highlighting giant palm fronds and tropical plants. A path at the center of the composition leads down to the water. Tall palm trees, blue skies with white clouds, and a welcoming calm landscape are characteristics of Heade’s work.

“The Great Florida Sunset” (1887) (54.25” x96’’) is the companion piece to “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica.” Heade’s love of each landscape he painted is obvious. He knew the shore reeds, the water plants, the variety of Florida palms, white lilies, exotic birds, and brilliant clouds at sunset. “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica” was purchased in the 1950s by a Californian. “The Great Florida Sunset” was sold in 1988. In 2015 the Marine Art Museum in Winona, Minnesota, paid $9.5 million for “The Great Florida Sunset” at a Sotheby’s auction, more than twice the price of other Heade paintings. The Museum previously had purchased “View from Fern Tree Walk, Jamaica.” The two paintings once again hang together.

After Heade moved to Florida, he developed an interest in native flowers. He created paintings of Cherokee roses, orange blossoms, apple blossoms, and roses, to name a few. Of special interest to Heade was the white magnolia which appealed to him because of his interest in natural history and the artistic beauty of the flower. He placed white magnolia blossoms on velvet cloth of a variety of colors to compare textures and elegant contours. “Giant Magnolias on a Blue Velvet Cloth” (1890) (15.1’’ x24.2’’) was purchased by the National Gallery of Art, Washington. D.C., in 1982.

Magnolia trees have a long symbolic history. They were a staple in southern gardens. They represented stability and longevity because of their long life. The white blossoms represent nobility and purity, and they are used in medicines. The fragrance and beauty of the large blossoms can withstand changes in weather conditions, representing endurance and fortitude.

Heade’s paintings are considered unique in American art as no other American artist created such a large collection of still lifes and landscapes. His still life paintings are considered by scholars to be among the most original paintings of the 19th Century. “Giant Magnolias on a Blue Velvet Cloth” is considered to be one of the finest still life paintings of the time. In 2004, the United States Postal Service selected this painting for the 37-cent stamp.

Heade’s paintings did not bring him a large income during his lifetime. When he died in St Augustine in 1904, he was largely unknown, although from 1800 to 1904, he wrote over 100 letters and articles on hummingbirds and tropical plants for Forest and Stream magazine. Attention was paid to Heade in the 1940s when art historians and artists rediscovered his work. His reputation was restored, and he is recognized today as one of the most important artists of his generation.

“A few years after my first appearance in this breathtaking world [1863], I was attacked by the all-absorbing hummingbird craze, and it has never left me since.” (Martin Johnson Heade)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

James Wilson says

Mrs. Smith

I just want to let you know that I appreciate your Looking at the Masters.